It was a natural phenomenon that made headlines around the world and conjured up visions of …Atlantis and sunken Calderas, yet the “seismic swarm” that plagued the south Cyclades in late January and February this year initially baffled scientists.

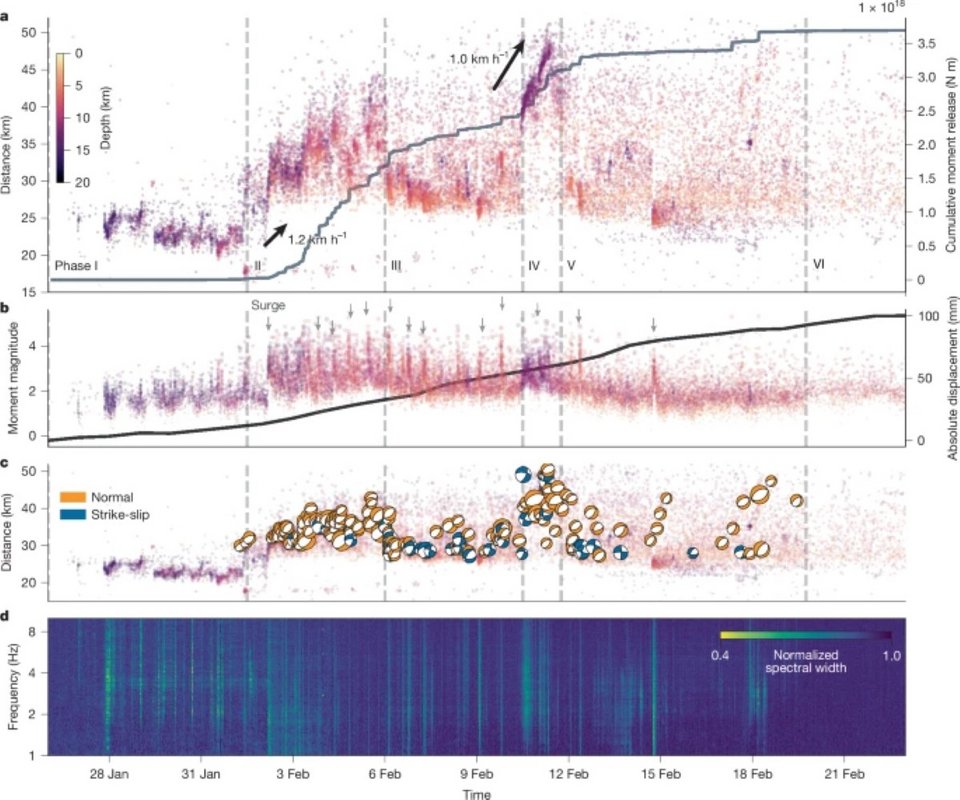

Seismographers measured more than 30,000 earthquakes in roughly a month and half, centered in a sea region bordered by the islands of Amorgos, Anafi, Ios and iconic Santorini, a pre-eminently volcanic isle.

Fast forward to September, and a study by 31 scientists from six countries published in the latest issue of Nature attributes the “seismic swarm” to volcanic activity – a surge, in fact, caused by the two volcanos very near Santorini being “inter-connecting”.

The earthquakes near Santorini began on Jan. 27 and continued for more than a month. Many of the island’s residents left, and there was a large mobilization of Greece’s civil protection services and even the military and police. In February, a state of emergency was declared on the “Instagram Island”, with schools closed for two weeks.

What the research on the earthquakes in Santorini reveals

The article published, entitled ” Volcanic crisis reveals coupled magma system at Santorini and Kolumbo,” supports the view of scientists who argued that volcanic activity was the root cause of the specific seismic activity.

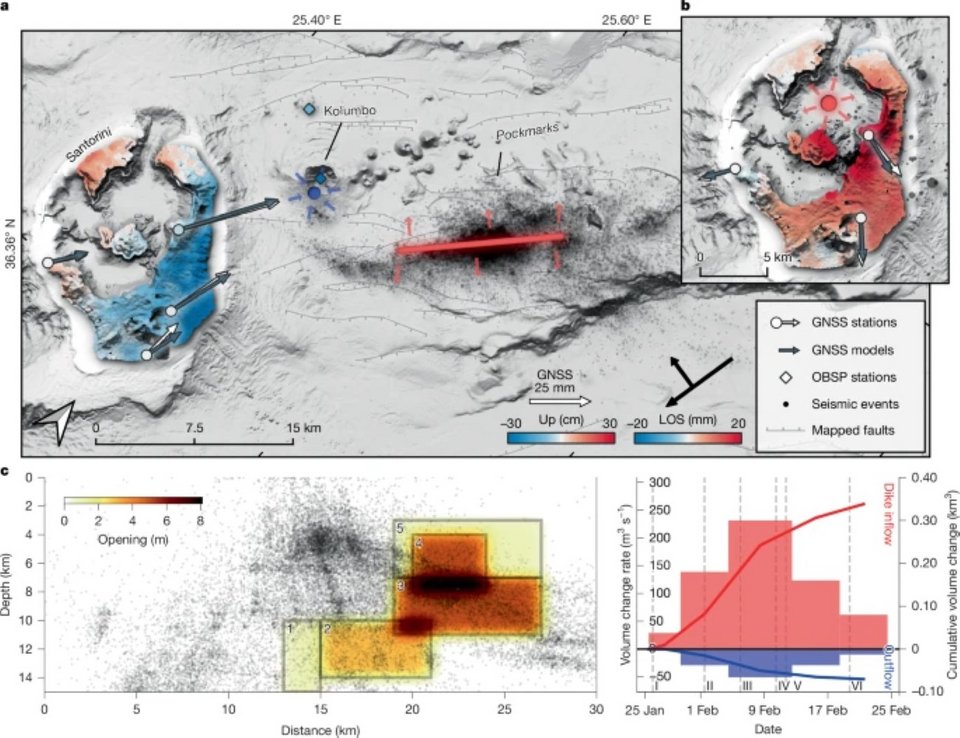

According to the research, “the 2025 volcano–tectonic crisis of Santorini simultaneously affected both volcanic centres, providing insights into a complex, multi-storage feeder system. Here we integrate onshore and marine seismological data with geodetic measurements to reconstruct magma migration before and during the crisis.

“Gradual inflation in the Santorini caldera, beginning in mid-2024, preceded the January 2025 intrusion of a magma-filled dike sourced from a mid-crustal reservoir beneath Kolumbo, indicating a link between the two volcanoes. Joint inversion of ground and satellite-based deformation data indicates that approximately 0.31 km3 of magma intruded as an approximately 13-km-long dike, reactivating principal regional faults and arresting 3–5 km below the seafloor.”