In the new era where the language of the digital world has spilled into everyday life, lexicographers face the dilemma of whether to enrich a dictionary or remove words that no longer resonate with contemporary users. The American Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, despite declining hardcover sales, has taken a bold step with the release of its 12th edition, adding 5,000 new words used by tech enthusiasts and influencers.

The dictionary, scheduled for release on November 18, is being updated for the first time in 22 years. Among the new entries are words like petrichor, teraflop, dumbphone, and ghost kitchen.

Petrichor describes the pleasant smell after rain that follows a warm, dry period. Teraflop is a unit measuring a computer’s processing speed. Dumbphones refer to the “basic” phones used before smartphones. Ghost kitchens, which grew particularly during the pandemic, are professional kitchens operating exclusively for online orders.

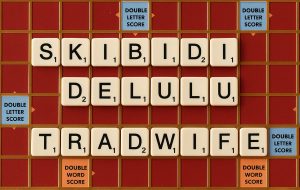

Other additions include cold brew (iced coffee), farm-to-table (direct from the farm), rizz (romantic charm), dad bod, hard pass (a strong refusal), adulting (handling adult responsibilities), and cancel culture. Compound terms such as beast mode (peak performance), dashcam, doomscroll (continuous bad news online), WFH (working from home), and side-eye (a suspicious glance) are also included.

All of these words were already available on Merriam-Webster.com. To make room for the new content, the publisher removed two sections from the 11th edition that contained limited biographical and geographical entries. According to Merriam-Webster president Greg Barlow, people rarely use dictionaries to learn about the location of Kalamazoo or the life of composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Outdated or rarely used words, such as enwheel (“to surround”), were also removed.

The new, hardcover edition weighs five kilograms and is released at a time when printed dictionary sales in the U.S. are declining. According to Circana BookScan, which tracks around 85% of the market, dictionary sales fell 9% over the past year.

Voices predicting the death of printed dictionaries have been around since online versions appeared. “Today, we are in the strange situation where people use the dictionary but don’t want to pay for it because they are used to getting things online for free,” said Grant Barrett, a lexicographer and former Oxford University Press dictionary editor.

Merriam-Webster records around one billion annual visits to its website, which also serves as a platform for language games. Over the past decade, the company’s total revenue has grown nearly 500%, mainly due to its digital presence. The new edition introduces features like themed word lists (“Words of the ’90s,” “Ten Words for Things That Usually Have No Name”), additional etymologies, and over 20,000 new usage examples. For devoted readers, it retains thumb cuts on the pages for easier navigation. Since the last U.S. printing company closed, production has been outsourced to a press in India.

Experts stress that printed dictionaries have a unique role, both as gifts and as tools for preserving languages or in schools that restrict mobile phones. “Having a printed dictionary signals the legitimacy of a language,” explains Lindsay Rose Russell, director of the Dictionary Society of North America. Many indigenous languages in America were never recorded because they were systematically suppressed. A dictionary is proof that a language exists.

Others see dictionaries as a form of reflection. “Many use them almost meditatively, opening to a random page and letting their mind wander,” says Grant Barrett.