Dozens of works by the world-famous sculptor Costas Varotsos—including many award-winning pieces—stand in public spaces across 12 countries (and in private collections), from Italy, Germany and France to Egypt, the UAE, Brazil and the United States.

He first became known to Athenians, as well as tourists and visitors to the capital, nearly half a century ago through his now-iconic sculpture The Runner.

That work was, in a sense, his artistic Big Bang. Made from his two beloved materials—metal and glass—it caused a sensation when it was installed in Omonia Square in 1988. Varotsos was just 33 years old at the time, having already completed his studies in Italy.

3. Varotsos’ ‘The Runner II’ stands before the Athens Hilton, reintroducing the artist’s iconic glass figure to the city’s public space after its removal from Omonia Square. Credit: Costas Varotsos

He has said in a past interview with Evi Kyriakopoulou that he struggled to handle the enormous publicity the piece brought him and escaped for a long period back to Italy, travelling like a nomad from city to city and working in the country he knew well.

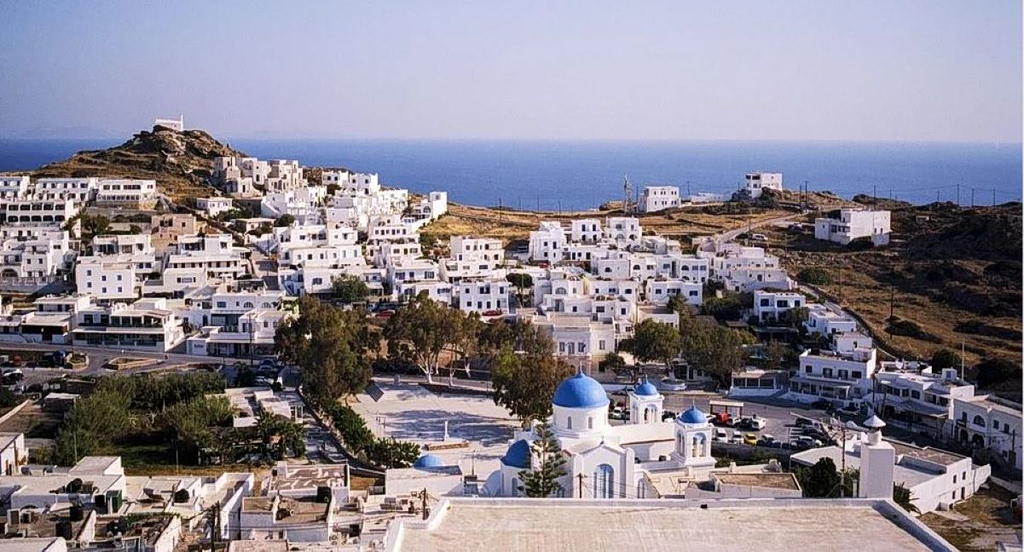

Now retired after 22 years of teaching at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and a permanent resident of his beloved Aegina, where he enjoys his privacy, Varotsos recently returned to the public eye at the unveiling of his latest work, Ark of National Memory.

The monument, which stands before the entrance of the Ministry of National Defence, is composed of illuminated glass columns that form a labyrinth for the visitor. Each column is engraved with a series of names—the 122,000 fallen soldiers killed in war from 1830 to 1974 (drawn from the archives of the Hellenic National Defence General Staff).

A pensive sailor stands before a column engraved with the names of fallen Greek soldiers, part of Varotsos’ ‘Ark of National Memory,’ located in front of the facade of the Greek Defense Ministry. Credit: Costas Varotosos

In a deeply candid conversation with To Vima International Edition, Varotsos discusses a wide spectrum of issues relating to art—education (where, he insists, we consistently fail), the commodification of art and our great ancient monuments, and the long-standing and repeated mistakes of the state in cultivating artistic, cultural and historical education—and ultimately a sense of identity—among young people in Greece.

While he highlights the profound distortions created by today’s art market—where a work is judged almost exclusively by its monetary value, “manipulated by a group of people who have built a system to make money and launder money”—Varotsos still believes that if a young artist devotes themselves wholly to their craft, if their life becomes their art, then despite the difficulty, it is possible to make a living from it.

Multiple award-winning sculptor Costas Varotsos has been for decades one of Greece’s best-known artists.

Your most recent and now widely discussed work, installed on the façade of the Ministry of Defence, is titled Ark of National Memory. What was your conception for incorporating the names of the 122,000 soldiers killed in wars from 1830 to 1974?

I had the idea of using the names themselves as material. So I printed them onto a glass labyrinth, so that when you step inside, these names of the fallen hover around you. These fallen emerge and move toward the light, upward and outward into space. They are not under the ground; they are beside you and above you, so that the visitor can comprehend what war means through death—and understand the significance of peace.

Credit: Costas Varotosos

Would you describe it as a patriotic work? And how do you define patriotism?

Look, patriotism is an emotion that, for me, is more complex. It’s not tied solely to those who died in patriotic wars. It is a patriotic feeling connected to everything that constitutes what we call Greece—our sky, our land, our seas, our culture, the people who struggle, and the love for one’s homeland. That is patriotism.

There is politics, there is the education of the people, and there is the historical and geographic layering that must exist in the memory of the Greek people—so that they know where they belong and what they represent. In other words, we are talking about education.

‘The Disembarkation’ 2014, memorialises the Otranto Tragedy. The artist uses the propeller of the Albanian migrant ship rammed by the Italian Coast Guard in 1997. Many passengers drowned.

Do we have good education in Greece, in your view?

Having been a professor [at AUTh], I understand the importance of historical layering and historical consciousness. Today, we have seen the destruction caused by the mishandling of the evolution of our educational system.

Where does the problem lie?

In centrifugal forces—forces that dissolve the nation, the state, the culture. When there is no education, when you don’t know what you represent culturally, you stop caring about your country. You don’t understand its importance, you don’t understand its history. Historical consciousness is crucial.

On education and the arts: five years ago the government effectively abolished arts education in all lyceums. What does that take away from students?

Look, when I observe developments, I always try to understand where the pathogeny lies. When I see something that I believe is wrong, I try to understand where that error stems from. A major mistake has arisen in art due to the identification of economic value with the whole. Essentially, everything is referenced back to the economy.

Yet the economy exists within a cultural framework.

What does art do? It works on the perceptual system of the average student or university student. It opens horizons; it discovers or proposes alternate ways of perceiving real time. That is what art does. It trains perception.

The artwork as financial, not artistic, value

Of course, there is a misunderstanding here. The economy—even in art—has reached a point where it has replaced the work itself. We no longer speak about what a work means or whether it is interesting. The question is: “How much does it cost?” Its price is what impresses people—not its image. This has happened in our perception of all phenomena.

Our ancient monuments as revenue streams

That is, regarding our ancient monuments, we do not focus on producing more translations, or on enabling our educational system to understand ancient Greek culture more deeply. Nor do we create more university departments to codify that culture.

We do not conduct research. We do not do that. What we do is look at our ancient monuments and consider how to make money from them. We see them as sources of financial profit, not of intellectual wealth.

So what happens? Within this climate, in the functioning of art within the university, someone says: “We don’t need this—if we have fewer professors, we pay less.”

‘Galaxy’ installation at the Washington Convention Center, Washington, D.C., USA.

I referred earlier to secondary schools, where arts classes have been abolished. They said interest was low—only 8%. And I wondered: if interest in maths or physics were at 8%, would we abolish those?

Exactly. These classes were abolished for economic reasons. I understand that current policy is shaped by people who make mistakes and later regret them. They say it was the wrong choice. It is good to recognise mistakes quickly—this applies to all political parties, everywhere on the planet.

Many mistakes in education

I believe all Greek governments want what is best for Greece and for education. I am not suspicious of any government. But mistakes happen. Many mistakes have been made—and continue to be made. This is one of those mistakes, because legislators and grassroots politicians fail to grasp how art functions. They do not understand what culture and art are, or that they are tied to the evolving nature of culture in all its forms.

The sculpture ‘Moon of Alexandria’ placed near The New Library of Alexandria, inaugurated in 2002. Credit: Costas Varotosos

Towards integrated learning and intellectual guidance

Returning to art in schools: if you remove a fundamental element—culture, meaning the arts—you hinder an integrated understanding of education.

When there is no cultural consciousness, no understanding of the importance of connecting values—culture, art, economy, technology, research—when elements that constitute a society are removed piecemeal, we begin saying “this is unnecessary” or “that is unnecessary.”

It reminds me of mechanics who dismantle an engine, fix it, then put it back together—and find spare screws left over. “We don’t need these; leave them out.”

For the mechanism called state or nation to function, all the screws must be in place. Nothing is more or less important. Intellectual guidance is essential. But someone making the curriculum says: “Why do we need painting now? What’s the point of the arts? Remove them.”

When you hear that only 8% of students are interested in the arts—who said that? Who analysed that? And by what criteria is 8% considered “little”? Who decided that?

How does the commercialisation of art and the market affect artistic creation?

The artwork itself has nothing to do with its economic value. The economic value of art is manipulated by a group of people who have built a system to make money and launder money.

How can a young artist make a living from their work?

They may not be able to. It is difficult. My father used to say to me when I was starting out: “How will you live, my child?”—because he knew my passion for it. And I told him: I don’t know how I will live, but the only thing I want to do now, in order to live, is to make art.

But that obsession, that absolute dedication, is what eventually creates a kind of gravity around you, and some sort of economy begins to form that allows you to survive. Not to become a millionaire—but to live. The pursuit of profit as an end in itself is incompatible with art.

Look, there is an unforgiving rule. Because art is the spearhead of history—confronting the recording of culture, and therefore history—the level of existential and intellectual commitment it requires is such that to follow it properly, you must devote your life to it. Completely.

To follow what we call primary creation, you must commit yourself to such a degree that your life becomes the work—you identify with your own work.

The magnitude of the sacrifice, and even the physical health required to sustain it, is enormous. It is very difficult for a person to endure it.

In your 22 years as a professor at AUTh, what did you learn from your students?

When I would close the amphitheatre door and have 200 students inside, we would begin to talk—and there were magical moments, through the synchronisation of the entire class. I cannot explain it because it is experiential. Magical moments occur when you and the students become one body, and you soar together to levels of research and astonishing intellectual focus. At that moment you feel culture being born. It is extraordinary. That is the moment of teaching and research—soaring together into unfamiliar and primary thoughts. It isn’t exactly teaching; it is the ability to synchronise 200 people and soar with them into unprecedented thinking.

What I received from my students is that they helped me reach things—touch things—that alone I could never have reached. In thought, in depth, in analysis of reality. I had an extraordinary relationship with my students.

I am very lucky, in that sense. Many times art has led me to magical moments in which I felt overwhelming truths and strength.

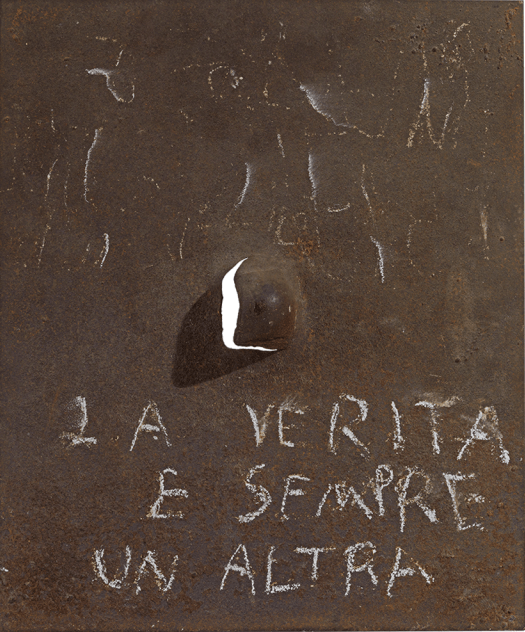

The pursuit of truth is a continuous chase. There is no truth as such. I made a work I love very much titled Truth Is Always Another (La verita e sempe un altra). When I was young, I realised that truth is always something else. The search for truth is endless. It has no end. The attempt to understand truth is a process. So truth itself is the process—not the discovery of truth.

Credit: Costas Varotosos