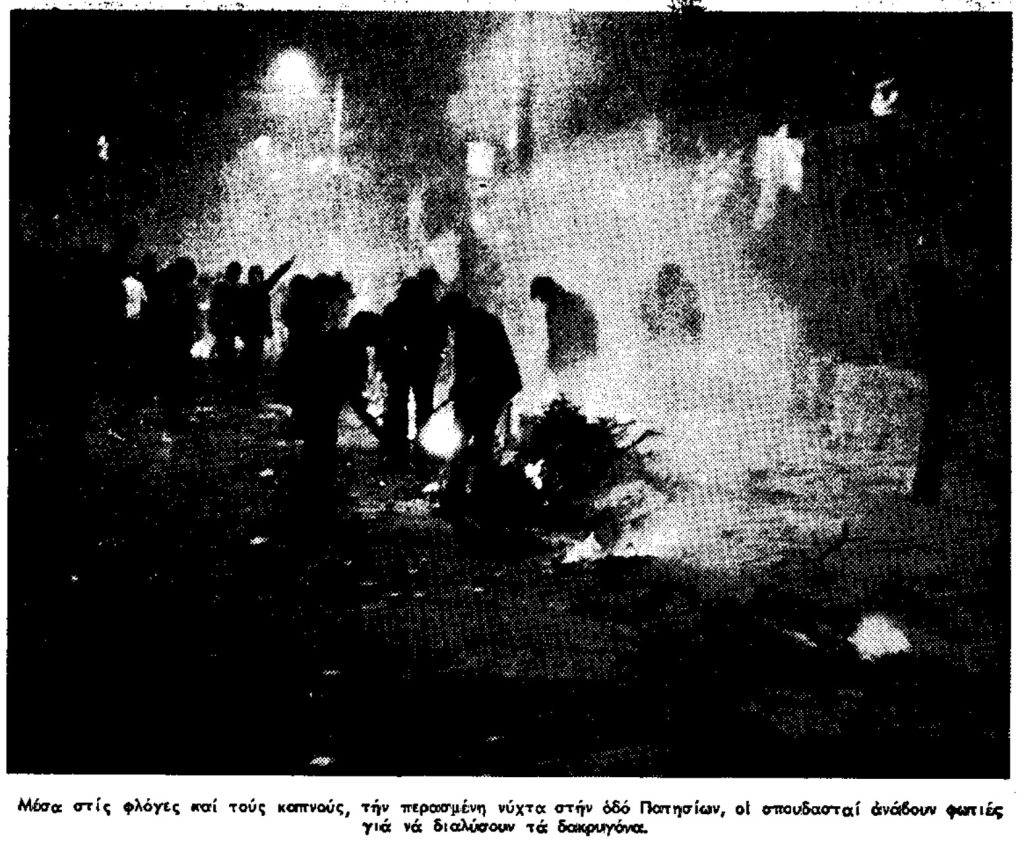

From the afternoon of Friday, November 16, Athens was already in turmoil. The Polytechnic — the Athens Polytechnic University — had become the heart of a swelling rebellion against Greece’s military dictatorship, known as the Junta of the Colonels (1967–1974). Streets were blocked. Citizens erected makeshift barricades to stop police and army vehicles. Large groups of demonstrators clashed with squads of riot police.

Workers, farmers, students, and ordinary Athenians flooded the streets in a wide circle around the Polytechnic. The junta’s police responded with heavy volleys of tear gas, beatings with clubs, and even live ammunition.

By that Friday night, November 16, the dictatorship moved decisively into counterattack. Armed forces were now confronting an unarmed population.

Contemporary newspapers captured the intensity of those hours. To Vima, in its November 17, 1973 edition, wrote:

“Buses, trolleys, and private cars coming from the Hilton had come to a standstill, and most passengers got out and continued on foot toward Syntagma, Akademias, and the other central areas.

“At 8 p.m., Patission Street, from Marinopoulos to Alexandras Avenue, had been flooded with people. Hundreds of police officers controlled Panepistimiou Street. Crowds had occupied the area of Chafteia and the beginning of Aiolou Street.

“Chants began at the Polytechnic and spread as far as Omonia. From Bouboulinas to 3rd of September Street, the area was packed tight with people.

“At 8:30 p.m. tear gas began falling in Omonia Square. People ran into side streets. The largest mass moved back toward the Polytechnic.

“In many cases the tear gas (launched from police vehicles) created the impression of gunfire. These vehicles chased demonstrators as far as Agios Panteleimonas on Acharnon Street.

“Protesters regrouped in Vathis Square and Exarchia Square, but quickly fled again as police continued launching tear gas.

“At 9 p.m. the main body of demonstrators had been pushed away from central Athens. Police continued firing tear gas to drive out shopkeepers and employees still in the area.

“By around 9 p.m., Stadiou and Panepistimiou Streets had emptied, leaving behind abandoned shoes and coats scattered across the pavement.

“At the same time, in Chafteia, a strong police force intervened to disperse demonstrators, firing shots into the air.

“Under police pressure, the protesters retreated and fell onto the shop windows of the Manhattan pastry shop and the Miraz novelty store. Soon, blood was visible on the pavement in front of the stores.

“Meanwhile, fires broke out on Patission Street outside ‘Minion.’ Police forces moved in immediately, and from an armored vehicle threw tear-gas bombs to disperse the demonstrators.”

These reports — now preserved in the historical archives of To Vima and Ta Nea — form a record of the escalating violence that consumed Athens through that night.

The First Casualties

The first confirmed dead of the Polytechnic Uprising was Spyridon Kontomaris, a former Member of Parliament with the Center Union party. He died on Stadiou Street from a heart attack triggered by tear-gas inhalation.

The first person killed by a bullet was Diomidis Komninos. He was standing outside the Polytechnic, helping carry wounded people to the occupied campus’s makeshift clinic. He was shot by members of the guard unit of the Ministry of Public Order.

Newspapers soon published additional names of the dead.

Ta Nea, in its November 17 edition, managed to reach the presses just in time to report what happened during the encirclement of the Polytechnic by tanks and the brutal assault that ended the occupation.

Readers today should keep in mind that censorship — though somewhat loosened at the time due to dictator Georgios Papadopoulos’ attempt at a controlled “liberalization” — still meant that information reaching the press passed through junta-controlled sources.

The Tanks Move In

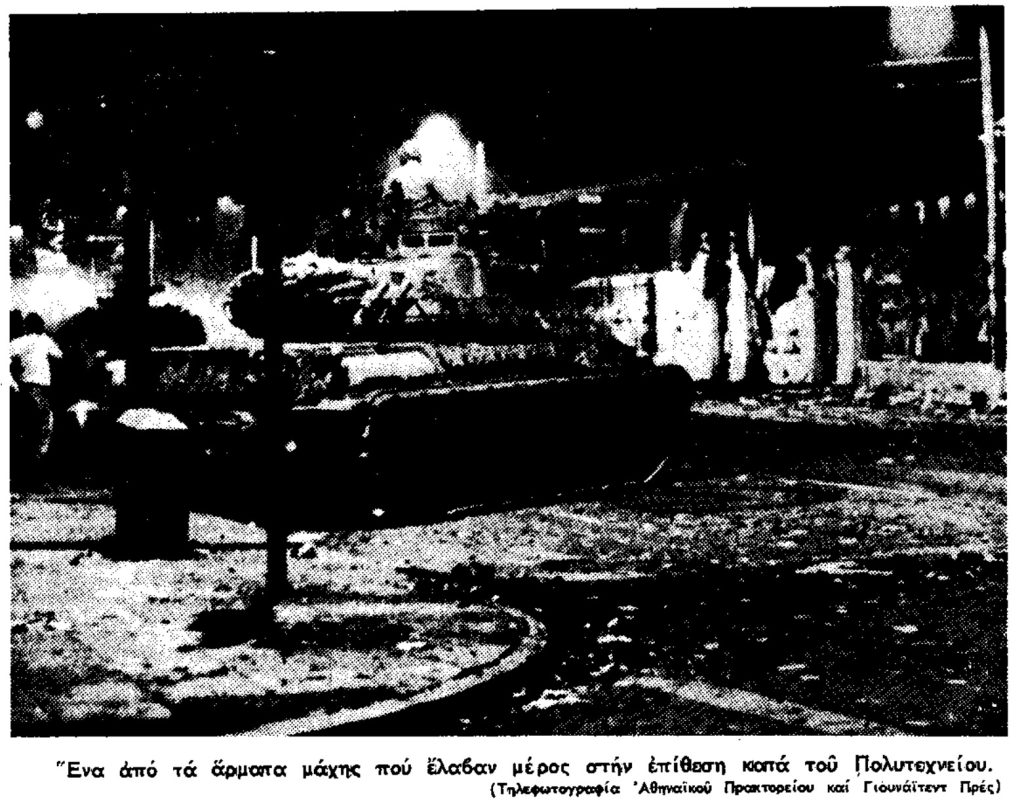

“Battle tanks, approaching from four converging directions, surrounded after midnight a large clearing operation by powerful police and special military forces at the Polytechnic,” Ta Nea reported. “This followed hours of street fighting in the surrounding roads, within a radius of two kilometers, between large groups of students and citizens and strong police forces.”

The final phase began shortly after midnight, when the first tanks appeared at the Ambelokipi intersection, coming from Goudi and Dionysos. At that moment, an area of 2–3 kilometers around the Polytechnic remained under the control of students and citizens, who were fiercely resisting police attempts to reclaim the streets.

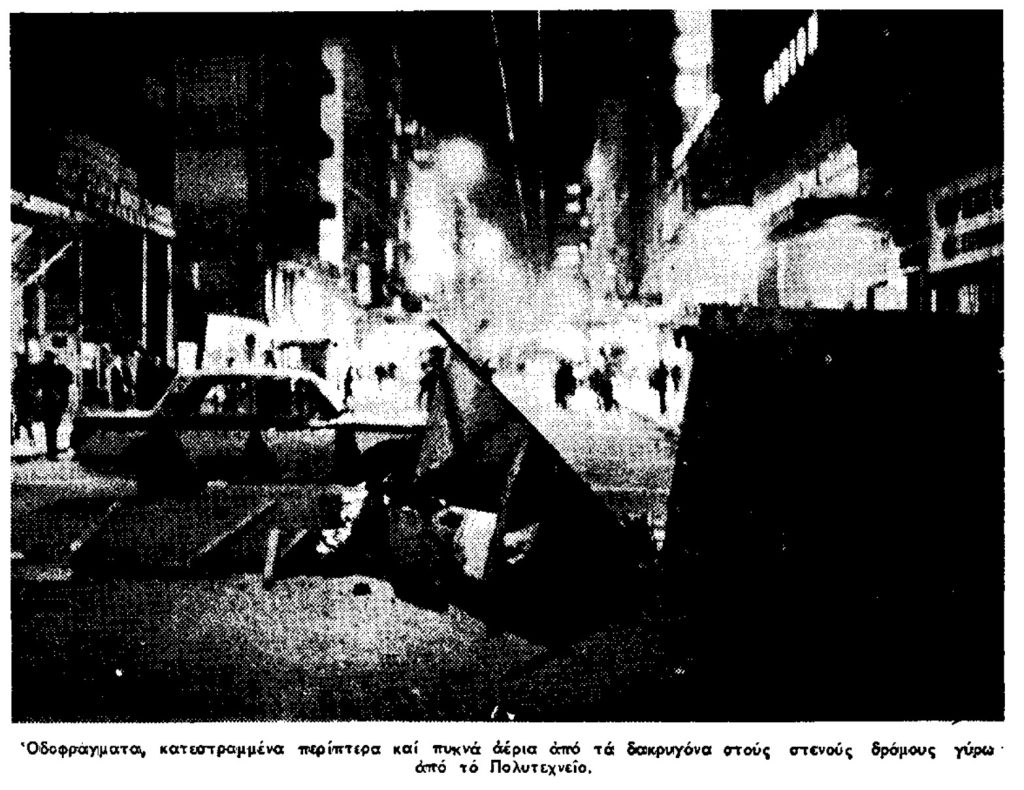

The tanks split off in different directions — some toward Alexandras Avenue, others toward Vasilissis Sofias and Panepistimiou. Those moving through Alexandras became stuck in the area known as “Sonia,” where cars had been positioned across the road as barricades.

A wide area bordered by Piraeus Street, Kapodistriou, Ipirou, Marni, Vathis Square, Stournara, Chalkokondyli, and Patission had also been sealed with cars, construction debris, buses, and trolleys placed sideways across the road. This blocked access directly in front of the Polytechnic.

To clear a path, police cranes had to drag the disabled buses and trolleys out of the way.

Street Battles Across Athens

Police forces simultaneously fought intense battles with demonstrators around Moustoxydi and Alexandras Avenue, as well as Patission and Ithakis Streets, where around 2:10 a.m. some 1,500 protesters had barricaded themselves.

There were also violent clashes at Ipirou and Patission. According to police sources, officers endured repeated attacks there and were in “tragic condition” for about 20 minutes before strong reinforcements arrived.

Police sources further reported fires and destruction of cars on Piraeus Street and in Vathis Square. They claimed that around midnight a police lieutenant was shot in Chafteia by someone using a hunting rifle; he was lightly wounded and taken to a nearby shop by a colleague’s sister.

Damage was also reported to the First Aid Station and to the Ministries of Justice, Social Services, and Public Order, the last of which allegedly faced three Molotov-cocktail attacks. Some of the toughest clashes took place around the Ministry of Public Order.

Armed police guarded all police buildings, state offices, key intersections, and streets where fighting continued.

By 1 a.m., the head of the Athens Prosecutor’s Office, Mr. Fafoutis, arrived at the Athens Police Directorate. Earlier, the head of the military police (YPEA), General Thomopoulos, had also arrived. A colonel from the elite LOK (Special Forces) was present in plain clothes.

At 2:15 a.m., the Athens police director was called to the Acropol Hotel, across from the National Archaeological Museum, arriving about ten minutes later.

The Final Assault

“The final phase of the operation began with an assault at 3 a.m. and ended within half an hour, with no clashes of special significance,” Ta Nea reported. “At the moment the tanks — 20 in number — appeared around the Polytechnic, a government source announced that the army’s intervention came after an urgent request from the police.”

Athens lived through a night of terror after a day of bloody clashes and widespread destruction of property, especially buildings and cars.

There were numerous arrests both inside and outside the Polytechnic. Casualties totaled four dead and around 130 injured, though no official announcement had yet been made.

A government source stated early that morning that tanks entered the capital shortly after midnight to support the police in restoring order. Police, the source claimed, had requested assistance from ASDEN, the Army’s Supreme Command of Interior Defense.

“At midnight,” the report continued, “the first tanks appeared at the Alexandras Avenue junction and reached the Polytechnic at 2:45 a.m.”

Students clung to the railings and began singing the Greek national anthem, shouting: “The army is with us,” “You are our brothers,” “No fraternal blood,” as tank searchlights illuminated the entire area.

The atmosphere was explosive, intensified by gunfire supposedly fired into the air.

But gunfire was not aimed into the air — despite the junta’s claims. Snipers stationed around the area fired directly into the crowd of students and citizens.

For an hour and a half, with tank barrels trained on them, the students continued chanting “The Army and the People Are One,” “You are our brothers,” “Army and People Together,” and singing the national anthem.

A little before 3 a.m., police and prosecutors used loudspeakers to once again demand that students evacuate.

At 3 a.m. sharp, a tank rammed the Polytechnic’s main gate, tore it down, reversed, and cleared the way for police and LOK commandos to enter, while machine-gun bursts were fired into the air.

Inside the courtyard, clashes broke out between police and students. Most of the assembled students fled through side exits into the surrounding streets, immediately forming new demonstrations.

Inside the buildings, more clashes took place. According to reports, the LOK commandos did not participate in the indoor fighting; they withdrew once police secured control.

By 3:30 a.m., all areas of the Polytechnic had been cleared. Ambulances began transporting the wounded — both those injured during the final assault and those hurt earlier.

Sporadic protests continued around Athens until 4:30 a.m., especially along Patission and Alexandras Avenue. As gunfire continued, cleanup crews swept the streets.

Meanwhile, the Athens police director, Mr. Christoloukas, went to the Political Office to brief Prime Minister Spiros Markezinis on developments and police actions.

Throughout the clashes, thousands of Athenians had come out of their homes, while church bells rang for hours.

By around 5 a.m., the tanks withdrew from the Polytechnic toward Pedion tou Areos. At the same time, about twenty tanks accompanied by “Jeeps” loaded with soldiers drove down Kifissias Avenue toward the center.

Aftermath and Historical Consequences

The Polytechnic Uprising ended at dawn on November 17. Its end was drenched in blood. According to the provisional list of the National Hellenic Research Foundation — with investigations ongoing — the identified dead from the November 1973 events number 24.

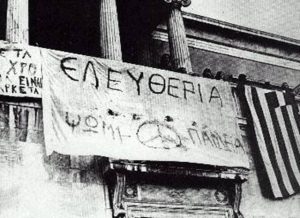

The uprising did not topple the dictatorship, as many hoped. But it sent an unmistakable message, in Greece and abroad: the country was captive under authoritarian rule, and a vital portion of the Greek people was willing to fight for freedom and democracy.

Only days later, on November 25, dictator Georgios Papadopoulos was himself overthrown by Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannidis, head of the military police (EAT-ESA), who imposed an even harsher regime.

Greece would be freed from the junta only months later, in July 1974, when the dictatorship collapsed under the weight of the national tragedy caused by Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus.