It is November 13, 1973. For more than six years — since April 21, 1967 — Greece has been held in the iron grip of the Colonels’ Junta, a military dictatorship that has silenced dissent and suspended democratic life.

The regime of Georgios Papadopoulos, after a rigged referendum in July 1973, abolished the monarchy and declared a Presidential Parliamentary Republic, appointing himself President. By October, he had named Spyros Markezinis as Prime Minister, promising vague steps toward elections.

But the dictatorship’s authoritarian nature remained intact. Its cosmetic “liberalization” fooled no one — least of all the country’s students.

The Brewing Storm

The student movement, already emboldened by protests earlier that year — notably the Law School occupation in Athens in February and similar unrest in Thessaloniki — had become the loudest voice of resistance. Young Greeks demanded not only free student elections but also the restoration of democracy and civil rights.

By mid-November, university campuses across the country were seething. On November 12–13, the first serious signs of coordinated revolt were appearing — small at first, but unmistakable in their intensity.

Contemporary reports in the newspaper “TA NEA” captured the rising tension among students and academics, as a society long silenced began to find its voice again.

Defiance from the Universities

At the University of Patras, the faculty of Physics and Mathematics challenged the dictatorship’s control, calling for university self-governance — a bold move, considering that the university’s president was a retired army officer appointed by the regime.

Meanwhile, the elected student committee of the Higher Industrial School of Piraeus (now the University of Piraeus) issued a public denunciation after one of its members was beaten by unidentified men in civilian clothes. The attack took place during a student meeting in a lecture hall officially recognized as an academic asylum, a space meant to be off-limits to police and political interference.

“Such actions prove once again who truly violates university asylum every day,” the committee declared. “We condemn this incident to every authority and to the entire student body.”

Voices from Abroad

Solidarity also came from outside Greece. The Association of Greek University Professors of Western Europe sent an open letter to TA NEA, expressing outrage at the regime’s crackdown on academic freedom:

“We express our deep concern that, for the second time in six weeks, the University of Athens has been closed to its students for reasons entirely unacceptable in democratic nations and contrary to the academic spirit.

Referring students to disciplinary councils simply for claiming their right to meet within their schools is deeply distressing. In Western Europe, where we teach, it is self-evident that students may gather freely whenever and wherever they wish.

We emphasize that policing students does not befit academic authorities — it threatens not only the operation of higher education but also the intellectual and scientific progress of the nation.”

Student Unity Across Greece

Across the country, local student unions — from Athens to the islands and northern Greece — began issuing joint statements of support. Associations representing students from Constantinople, the Dodecanese, Corfu, Larissa, Central Greece, Karditsa, Trikala, Aetolia-Acarnania, Corinth, Ilia, Arcadia, Messinia, Patras, Kefalonia, Chios, Epirus, and Crete all signed a collective declaration denouncing the repression faced by their peers in Thessaloniki.

They described how attempts to hold general assemblies were thwarted by intimidation and financial blackmail — including a case where a hall owner, after pressure from authorities, increased the rental price from 12,000 drachmas to 500,000 overnight.

“We demand an immediate resolution of their problems — the free convening of assemblies and transparent elections,” their statement read. “We call for an end to all forms of pressure that continue to obstruct democratic thought and action.”

The Days Before the Explosion

By the night of November 13, Athens was already simmering. Within twenty-four hours, students would occupy the Polytechnic University, transforming it into the beating heart of a national revolt.

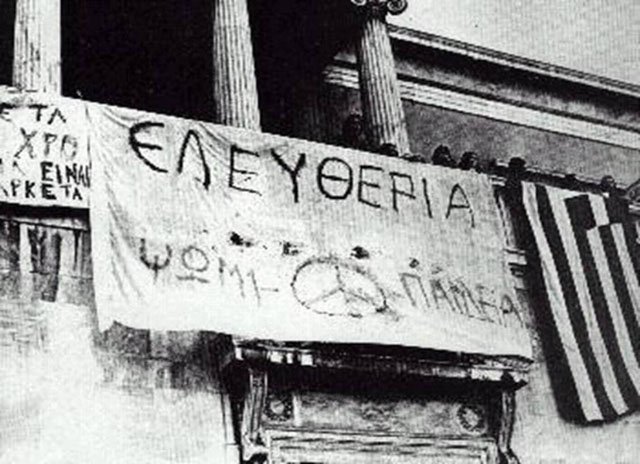

What began as protests for student rights would soon become a full-scale rebellion — one that shook the foundations of the dictatorship and etched the words “Ψωμί, Παιδεία, Ελευθερία” (Bread, Education, Freedom) into Greek history.

The uprising that followed would not only mark the beginning of the end for the Junta — it would become a lasting symbol of the Greek people’s unyielding demand for democracy.