On the evening of September 30, 1968, Greece witnessed one of the deadliest accidents in its railway history. Near the coastal town of Derveni in Corinth, two passenger trains packed with people collided with terrifying force. The result was catastrophic: 34 lives lost and 125 injured.

The trains that day were unusually crowded. Thousands of passengers had traveled to their hometowns to take part in the military junta’s rigged referendum on a new constitution. As they returned to Athens, tragedy struck.

One train from Kyparissia stalled just 500 meters before the Derveni station after a passenger fainted. While first aid was being administered, another train from Kalamata, only ten minutes behind on the same track, approached at nearly 80 km/h. With a bend obscuring visibility, its driver never saw the stopped train until it was too late.

A Fatal Chain of Events

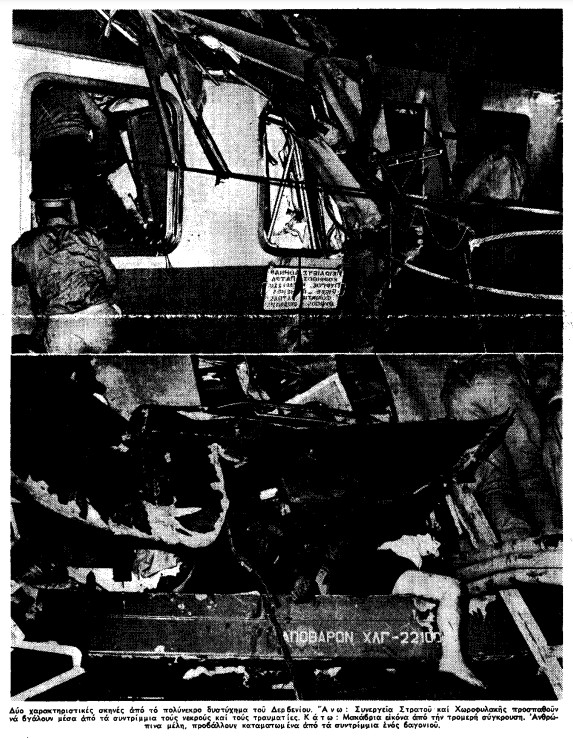

Archival reports from Greek newspapers To Vima and Ta Nea paint a harrowing picture of what followed.

Passengers recall how the first train halted after the emergency brake was pulled—accounts vary whether for a fainting sailor, an elderly woman, or even a sick child. Some passengers tried to carry the unwell traveler to a local clinic. In the meantime, the second train thundered down the track.

The impact was described as “a thunderbolt”, shaking carriages like an earthquake. Fifteen wagons were crushed. Survivors were thrown against windows, smashing glass in desperate attempts to escape. Parents clutched screaming children; others leapt from windows into nearby fields as panic rippled through the carriages.

“The cries of the wounded and the sobbing of children were the only guides for rescuers,” reported Ta Nea.

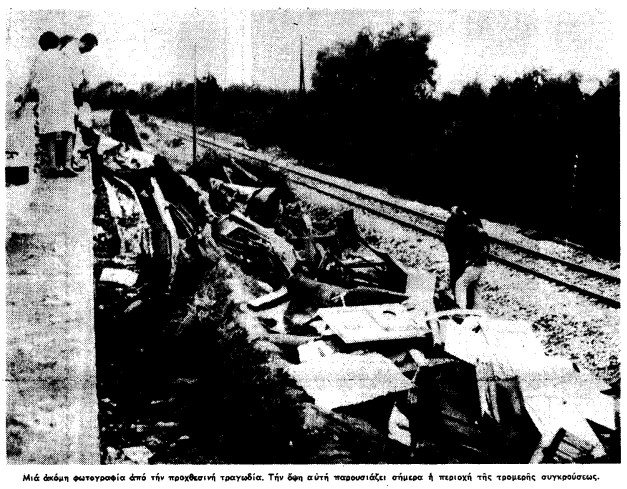

For hours, rescue teams—soldiers, police, and civilians—worked under floodlights to cut through mangled steel. The scene was horrific: twisted bodies, blood-stained uniforms of medics, and ambulances ferrying the injured through the night.

Voices From the Wreckage

One survivor, builder Nik. Kapsis, recounted:

“I was traveling with my pregnant wife and sister. We boarded in Patras. At Derveni, the train stopped because a woman’s child fainted and she pulled the emergency brake. Moments later, the collision came. Everyone tried to save themselves. For my sister, I still know nothing…”

Such testimonies reveal not only the chaos but also the unbearable human toll of that night.

Preventable Tragedy

Investigations later highlighted critical failures in railway safety. Both the driver and supervisor of the first train knew a second train was following closely but failed to provide proper warning signals—red flags or lanterns—to alert the oncoming locomotive.

When railway staff finally attempted to place signals at a safe distance, it was too late. The second train, driven by Eleftherios Kourouniotis, smashed into the stationary carriages, its engine embedding itself into the last two wagons.

The Railway Workers’ Union defended staff, noting the first train’s length—over 200 meters—meant the signalman ran an additional 150 meters beyond the tail, but even that was not enough to prevent the crash.

A Dark Page in Greek History

The Derveni crash of 1968 was more than an accident—it exposed the dangerous shortcomings of Greece’s rail system under the dictatorship. Overcrowding, lack of signaling systems, and poor coordination turned a fainting passenger into the spark of disaster.

Fifty-five years later, the tragedy remains a haunting reminder of how fragile safety can be when infrastructure fails. The wreckage, the cries, and the desperation of that night are etched into Greece’s collective memory as one of the darkest pages of its railway history.