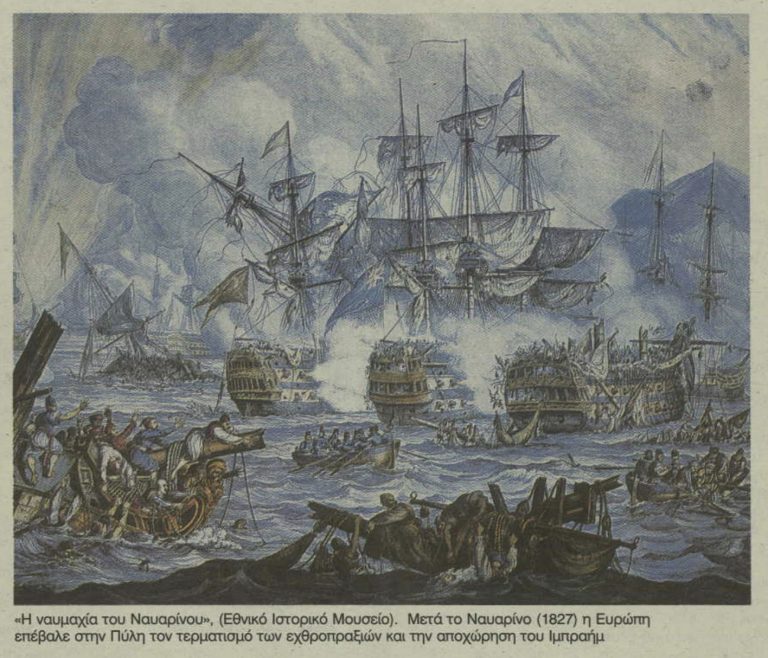

On October 20, 1827, the quiet waters of the Bay of Navarino in southern Greece erupted into one of the most decisive naval battles in history. The combined fleets of Britain, France, and Russia — allies of the Greek revolutionaries — faced off against the formidable Ottoman–Egyptian armada, in a confrontation that would shape the destiny of Greece and the balance of power in Europe.

The Battle of Navarino was not only the turning point of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829); it was also the unintended result of diplomacy gone wrong. The Sultan’s refusal to accept the Treaty of London (July 1827) — an agreement designed to pave the way for Greek autonomy — set the stage for an explosive encounter that no one had formally declared.

“An Unfortunate Incident” That Changed History

As To Vima wrote in its 2006 historical archives:

“The first official involvement of foreign powers in Greek affairs came with the Battle of Navarino — an event that forever defined the Great Powers’ relationship with the Ottoman Empire. The British government called it an ‘unfortunate incident.’”

Indeed, the battle began almost by accident. A series of tense exchanges and misunderstandings led the cannons of the Allied fleet to fire — and once the first shot rang out, there was no turning back.

What followed was a storm of fire and iron.

The Battle Unfolds

The British flagship Asia, under Vice-Admiral Edward Codrington, led the way into the bay, followed by the frigates Dartmouth, Albion, and Genoa. Behind them came the French fleet under Admiral de Rigny and the Russian fleet commanded by Admiral Heyden — in total, 28 warships armed with 1,298 cannons and 17,500 crewmen.

At first, the bay was eerily calm. Then, suddenly, gunfire erupted from both sea and shore.

By nightfall, the once-mighty Ottoman–Egyptian fleet — 89 ships, 2,436 guns, and 22,000 men — lay in ruins. Only 29 shattered vessels remained afloat, the rest sunk or ablaze.

The Allies lost 655 men; the opposing forces suffered over 6,000 casualties.

British statesman John Russell, later Prime Minister, called it “the most righteous victory since the beginning of time.”

A “Happy Mistake”

The Allied commanders had originally sailed to Greece to enforce a ceasefire, not to start a war. Their mission, as set out in the Treaty of London, was to pressure the Ottomans to end hostilities and withdraw their forces from the Peloponnese.

But their diplomatic overtures failed. Even a secret meeting at Pylos on September 25, 1827, between the Allied admirals and the feared Ottoman commander Ibrahim Pasha, produced no result. When the Allies anchored inside the bay to show force, a single shot — whose source remains disputed — sparked a full-scale battle.

As French historian Sergeant later described it, Navarino was “a fortunate mistake.”

The Aftermath and Global Impact

The shockwaves of Navarino were felt across Europe. To liberal circles, it symbolized the triumph of freedom over tyranny. For the Russian Empire, it was a chance to expand influence in the Balkans.

In Britain, however, the reaction was mixed. Both Tories and Whigs condemned the event for upsetting the fragile balance of power with Russia. Codrington was even recalled from command, replaced by Admiral Malcolm, and his crews were denied the traditional victory bonuses — a sign of official disapproval.

The Battle That Opened Greece’s Path to Freedom

Though the battle was decisive, it did not immediately secure Greek independence. Another two and a half years of diplomacy and warfare — culminating with the French expeditionary corps under General Maison — were needed before Greece finally won its freedom.

As French historian Edgar Quinet wrote:

“The Greeks owe the beginning of their national life not to charity, but to their own hands. Europe intervened only after seven years — when it had had its fill of the spectacle of slaughter.”

Even so, as Ta Nea wrote in its 1977 retrospective:

“Navarino was a decisive turning point in the struggle of 1821 — even if, for many scholars, it was also the beginning of foreign intervention in Greece.”