As Greece endures yet another sweltering heatwave this week, it brings back haunting memories of a disaster that scarred the nation almost four decades ago — the killer heatwave of July 1987.

For nine blistering days, from July 20 to 28, temperatures soared beyond 40°C (104°F), turning Greek cities into ovens and homes into death traps. But this was not just a spell of uncomfortable weather. It became one of the deadliest natural disasters in the country’s modern history, officially claiming the lives of more than 1,300 people.

Most of the victims were elderly, poor, or medically vulnerable — and they died quietly, often alone, in stifling apartments without air conditioning or access to basic healthcare. At the time, domestic air conditioning was a luxury, not a norm. Public infrastructure was woefully unprepared. And climate awareness was still in its infancy.

“The Whole Country Is Boiling”

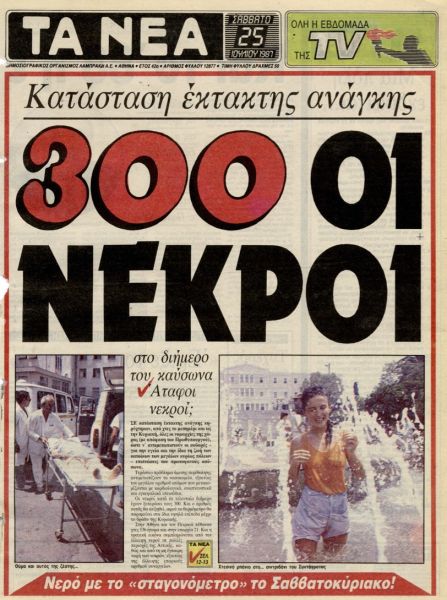

Greek newspaper headlines at the time were grim. “The whole country is boiling like a giant furnace,” reported TA NEA on July 22, 1987. The meteorological service predicted no immediate relief.

Even early on, the consequences were deadly. “Yesterday’s heatwave contributed to the deaths of four people — two in Athens and two in Volos — all suffering from heart conditions. Dozens more, mostly elderly, were hospitalized with cardio-respiratory problems,” the report read.

But this was just the beginning.

A Silent Epidemic of Death

Hospitals quickly became overwhelmed. Morgues reached capacity within days. Funeral homes couldn’t keep up. “A massive problem has emerged, and it’s expected to grow in the coming days,” reported TA NEA. “Hospital morgues are already full, and similar issues are being reported at mortuaries across the country.”

The death toll was rising so quickly that bodies had to be stored in makeshift locations. The capital, Athens — home to nearly 4 million people — began to resemble a ghost town.

Athens: A City Under Siege

By July 26, TO BHMA described Athens as a “dead city.”

“The capital is still a ghost town. Those who survive can only hope that by tomorrow afternoon, this deadly heatwave — the most lethal in recent Greek history — will begin to ease.”

The paper captured the national mood with brutal clarity: “The only topic of conversation these days is the unbearable and unrelenting heat. Every other issue has been pushed aside. And once again, Greece wins a gold medal — not in athletics, but in disorganization. The country has proven utterly unprepared for any kind of natural disaster. In many areas, even running water was unavailable.”

By then, the scale of the crisis was undeniable: hundreds dead, thousands confined to their homes, and hundreds of thousands suffering in suffocating heat, in what the paper called a city where “life has become unlivable.”

A Tragedy Born of Hubris and Unpreparedness

The summer of 1987 marked a dark turning point. It exposed not only the vulnerabilities of Greece’s public health system and urban infrastructure but also a deeper environmental blind spot.

In the 1980s, Greeks were only beginning to understand the environmental cost of rapid urbanization — the unchecked spread of concrete, the choking pollution, the absence of green spaces. Yet, in the years that followed, little changed. The warnings went unheeded.

Today, Greece — like much of the world — is grappling with the undeniable consequences of climate change: more frequent and intense heatwaves, longer wildfire seasons, unpredictable weather patterns, and vulnerable cities pushed to their limits.

The deadly heatwave of 1987 is no longer a distant memory. It is a warning that continues to echo in every stifling summer day. And as the mercury rises, the question lingers: have we truly learned anything — or are we still one hot week away from disaster?