On this day, 6 December 2008, 15-year-old Alexandros Grigoropoulos was shot dead by police officer Epaminondas Korkoneas in the Athens district of Exarchia—a neighbourhood long associated with youth activism and clashes with authority.

His killing sparked one of the most intense eruptions of public anger in modern Greek history, exposing a deep crisis of trust between citizens and the state. Within hours, the news ignited a massive and prolonged uprising across the country, once again bringing the issue of police violence to the forefront—an issue that was anything but new.

Decades earlier, from the 1960s through the 1980s, incidents of state repression had already fuelled public outrage. Many were followed by incomplete investigations, minimal accountability and a growing suspicion that the rule of law did not apply equally to the country’s security forces.

Among the most defining cases—now etched into Greece’s political memory—were the deaths of Sotiris Petroulas (1965), Iakovos Koumis and Stamatina Kanellopoulou (1980), and 15-year-old Michalis Kaltzas (1985).

The Death of Sotiris Petroulas (1965)

Sotiris Petroulas, a 23-year-old economics student at ASOEE (Athens University of Economics), was killed on 21 July 1965 during the massive demonstrations of the “Iouliana”, a constitutional crisis that shook Greece months before the country slid toward military dictatorship.

During the protests, police attacked demonstrators with batons and tear gas in central Athens.

To VIMA, published on 22 July 1965, described a city turned into a battlefield:

“The scenes at Syntagma Square between police and demonstrators, and the fanaticism shown by police forces during the clashes, could only recall a fascist regime…”

Wielding clubs, police charged at protesters, who responded by erecting barricades with wooden planks torn from nearby construction sites. Cars were overturned and set ablaze to slow the advancing riot squads.

At the height of the clashes, Petroulas collapsed to the ground, severely injured. Eyewitnesses testified that police fired a tear gas canister directly into the crowd at head level. The projectile struck Petroulas in the face.

When his body was taken to the morgue, police imposed strict restrictions. They attempted to hand over the body for burial before relatives arrived—prompting outrage and intervention from opposition MPs.

Two Autopsies

Under pressure from the family, a second autopsy was conducted with independent doctors present. The findings matched the first:

“Death resulted from an internal meningeal hematoma caused by gas pressure from a tear-gas bomb that exploded near his face…”

Yet claims have persisted for decades that Petroulas may have been strangled by police while being carried away—claims that official examinations never fully dispelled.

His funeral became one of the largest demonstrations of the “Iouliana,” with crowds shouting “Immortal,” “Sotiris lives,” “Democracy,” and “114”—a rallying cry defending the constitution.

As one contemporary report wrote:

“The death of Petroulas is the blood price once again paid by the country’s students in their struggle for democracy and against authoritarianism.”

Iakovos Koumis & Stamatina Kanellopoulou (1980)

On 16 November 1980, during the annual march commemorating the 1973 Athens Polytechnic uprising against the junta, 26-year-old Cypriot student Iakovos Koumis and 21-year-old worker Stamatina Kanellopoulou were fatally injured in the center of Athens.

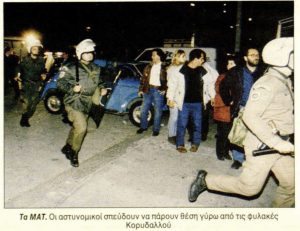

Both happened to be in areas where violent clashes broke out between demonstrators and the MAT riot police. Reports from the time described severe head injuries and excessive force. Public debate quickly shifted to police practices in the years after Greece’s return to democracy.

Despite lawsuits, months of investigation and public outcry, no perpetrators were ever identified.

To VIMA wrote on 25 November 1980:

“According to the police, the perpetrators of Kanellopoulou’s fatal injury are unknown… They may have been policemen, demonstrators—or it might have been an accident.”

In the case of Koumis, who died after days in a “clinically dead” state, no case file was even opened.

In May 1982, after more than a year of judicial inquiry, To VIMA reported:

“The investigation has concluded without locating the perpetrators of two deaths and dozens of injuries… Police authorities showed reluctance to assist, providing vague and contradictory information.”

All charges were eventually dropped. No one was convicted.

Michalis Kaltzas (1985)

On 17 November 1985, again during the Polytechnic anniversary, clashes erupted in Exarchia.

Amid the chaos, 15-year-old Michalis Kaltzas was shot in the back of the head by special police guard Athanasios Melistas.

The killing ignited one of the most defining debates of the post-dictatorship era on police violence.

A week later, Ta Nea published a detailed investigation titled “Police Officers Who Kill Are Not Remanded”, highlighting that Melistas’ immediate release was not an exception but part of a longstanding pattern:

“None of the police officers who in recent years have shot and killed or injured civilians are currently in pre-trial detention… Courts rarely prosecute such cases.”

The article reviewed numerous earlier incidents in which officers shot civilians—including teenagers and bystanders—without meaningful judicial consequences.

A Systemic Problem

These cases—Armaos, Kalafatas, Kontopidis, Sinioros, Boul, Taylor, Kechaidis, Gouliovas, Spyropoulos—created what the newspaper called a structural culture of impunity.

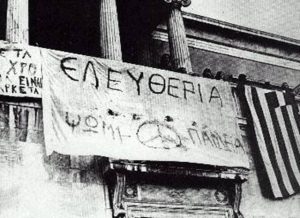

The public’s reaction to Kaltzas’ murder, however, was unprecedented: building occupations, two ministers offering (unaccepted) resignations, removal of the police leadership, 42 arrests, dozens of injuries and extensive damage across Athens.

As Ta Nea noted:

“All these events raise a critical question: shouldn’t Justice finally show greater urgency so that these cases reach the courtroom?”

First Verdict – Two Years with Suspension

Three years later, on 23 September 1988, the Mixed Jury Court sentenced Melistas to two years in prison, suspended, for “manslaughter with intent committed in a fit of rage.”

He did not spend a single day in jail.

As Ta Nea wrote the next day:

“The courtroom erupted in applause—mostly from uniformed and plainclothes police officers.”

Kaltzas’ mother declared:

“If all policemen who are meant to protect citizens are like him—and like those who appeared in court—then God help us.”

Appeal – Melistas Acquitted

In January 1990, despite forensic testimony confirming that Kaltzas had been killed by a direct shot to the back of the head from a .38-caliber bullet, the Appeals Court fully acquitted Melistas.

It was the final act of a legal trajectory that began with his immediate release in 1985, continued with a minimal suspended sentence, and ended with complete exoneration.