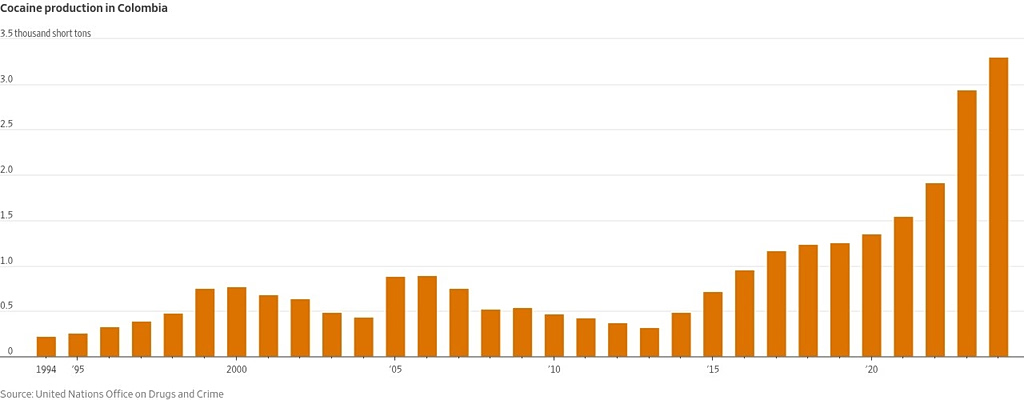

Once the most reliable U.S. ally in Latin America, this country is now racing to mend ties with Washington after its leader fell out with President Trump . Its biggest challenge is controlling a record surge in cocaine production.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro headed to Washington for a White House meeting Tuesday with Trump at a time when his country is producing almost nine times as much cocaine as in 2012. Heavily armed narcotics-trafficking militias have doubled in size since 2022. So much cocaine is reaching American shores that the U.S. has threatened to cut off foreign aid and sanctioned Petro for not doing enough to stop it.

Ahead of Petro’s meeting with Trump, Gen. Pedro Sánchez , the Colombian defense minister, visited Washington with a message that the country is cracking down.

The security services here say they are destroying a cocaine-production lab every 40 minutes. They seized almost 2 million pounds of cocaine last year, a record. And, they say, they have pinched supply so much that cocaine prices are rising.

“It’s reached its peak,” Sánchez said by phone, taking a break from talking to U.S. officials in Washington last month. “The rate of growth has declined.”

James Story , a former U.S. diplomat who led antinarcotics efforts in Colombia from 2010 to 2013, said Colombia has indeed interdicted a lot of cocaine, but the reason isn’t very impressive.

“You have record seizures of cocaine, sure, because you have record production of cocaine,” said Story, a former ambassador to Venezuela. “They’re producing a ton of cocaine.”

The fate of U.S.-Colombia ties might come down to the chemistry between Trump and Petro, a leftist former guerrilla who is openly hostile to capitalism, close to Cuba’s Communist government and frequently critical of the U.S., including its signature antidrug campaign of airstrikes on speedboats ferrying drugs from South America.

Trump has called Petro “a low-rated and very unpopular leader, with a fresh mouth toward America.” Last fall, the U.S. canceled Petro’s visa and froze any assets he may hold in the U.S., accusing him of allowing drug cartels to flourish. The U.S. hasn’t provided evidence to justify placing him on the Office of Foreign Assets Control list, typically reserved for major traffickers.

Trump even suggested that Colombia could be next the day after U.S. commandos extracted Venezuelan autocrat Nicolás Maduro from Caracas, Venezuela.

But Trump invited Petro to the White House after a 40-minute conversation on Jan. 7. Trump said he came away open to hearing Petro’s side in person. Petro, 65 years old, said he told Trump that political figures from Colombia’s “extreme right” had spread false rumors to undermine his leftist rule.

The hope for Petro is that he can reset relations that had been close since the 1980s. Successive Colombian governments received about $14 billion in U.S. aid to fight cocaine trafficking and insurgencies in close coordination with Washington—a partnership unmatched in the region.

The coming meeting between the two leaders is a “huge step in the right direction,” said Daniel García-Peña , Colombia’s ambassador to Washington. But he added: “That doesn’t mean the differences are going to be resolved.”

One problem might be that Petro denies that cocaine trafficking is flowing north from Colombia like never before. He told a huge crowd of supporters gathered on Bogotá’s central square recently that such assertions were a “bag of lies.”

“They tell this story to Trump,” the president said in his speech. “There’s no evidence at all.”

Evidence from Colombia’s countryside—including United Nations monitoring of drug crops, military data and interviews in coca-growing regions—shows otherwise.

Figures collected last year by the U.N. show Colombia was covered with 647,000 acres of the leaf essential to making cocaine—445% more than in 2012, when the U.S. and Colombia had dramatically reduced the size of the coca crop and cocaine production after a dozen years of spraying chemicals from crop dusters. The amount of cocaine that can be produced reaches 3,300 tons, nearly nine times as much as the U.N. drug researchers reported was produced in 2012.

Since Petro took office in 2022, drug militias, each fielding thousands of heavily armed fighters, have doubled in size to more than 25,000 members. The National Liberation Army, or ELN, counts 6,700 members, hundreds of them in Venezuela. The Gulf Clan, which the U.S. recently designated a foreign-terrorist organization, has about 9,000 members. And other groups made of renegade guerrillas who rejected a 2016 peace accord have 9,200 members.

In his mountainous home in southwest Cauca province, Uverney Ijaji , 42, who helps lead a cooperative of farmers, says coca remains central to the local economy and to the gangs that have grown strong trafficking it.

“The armed groups have taken territory, and so people from one place can’t cross over to where the other group is,” he said, calling government assertions that it had gained back some ground “a lie.” He added, “The farmers around here find themselves caught in the crossfire.”

This isn’t Colombia as it was a quarter-century ago, when the U.S. embarked on a bipartisan, multibillion-dollar program to curb cocaine production and contain Marxist guerrillas who some policymakers in Washington believed could seize power.

By the early 2010s, the industrial-sized fields of coca in Colombia’s remote far south had been decimated. Nationally, the coca crop had been reduced by 70%. And the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC—once Latin America’s largest and most powerful guerrilla group—had abandoned its goal of taking power and instead entered peace talks.

“It was an incredible drop,” said Story, the former diplomat who once led antidrug efforts. “There was a point in time where we no longer had any coca to spray in southern Colombia.”

The reversal since then—which experts trace to a 2015 court ban on aerial fumigation—is visible across remote regions, particularly those close to the borders of Venezuela and Ecuador where groups compete for control of booming drug routes.

Hugo Gomez , who oversees a program by the American group Mercy Corps to help coca producers switch to legal crops, said farmers in the Catatumbo region next to Venezuela breed heartier crops that result in more harvests. They also now cram 36,000 coca bushes per hectare, as opposed to 12,000 in the past.

The increased productivity means more cocaine available to traffic to the U.S. and the world’s expanding markets, from Australia to Eastern Europe.

“It’s not only an increase but in the density of plants, the number,” driving the growth in cocaine, Gomez said. “That means technological advances that are making coca fields more productive are leading to an increase in cocaine.”

Unilateral cease-fires called by the government to spur armed groups into peace talks have eased battlefield pressure, military analysts said, allowing militia commanders to recruit more fighters and use drug profits to upgrade their arsenals.

In Catatumbo, that has led 100,000 people to flee their homes in the past year as the groups battled over drug routes. And Jose Abril , a farmer who has grown coca but fled amid the violence, said the state failed to make the sustained investments to persuade farmers to switch crops.

“At this moment, Catatumbo is in a war without hope that there’s going to be any change,” he said. “As long as the ELN is there with other groups, they’re going to fight it out. It’s impossible there’ll be an end to it, impossible that there’ll be an end to the coca.”

Write to Juan Forero at juan.forero@wsj.com