BERLIN—A dozen senior German officers convened at a triangle-shaped military compound in Berlin about 2½ years ago to work on a secret plan for a war with Russia.

Now they’re racing to implement it.

Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine ended decades of stability in Europe. Since then, the region has embarked on its fastest military buildup since the end of World War II. But the outcome of a future war won’t depend only on the number of troops and weapons in the field.

It will also hinge on the success of the monumental logistical operation at the heart of Operation Plan Germany, the 1,200 page-long classified document drafted behind the nondescript walls of the Julius Leber Barracks.

The blueprint details how as many as 800,000 German, U.S. and other NATO troops would be ferried eastward toward the front line. It maps the ports, rivers, railways and roads they would travel, and how they would be supplied and protected on the way.

“Look at the map,” said Tim Stuchtey, head of the nonpartisan Brandenburg Institute for Society and Security. With the Alps forming a natural barrier, North Atlantic Treaty Organization troops would have to cross Germany in case of a clash with Russia, he added, “regardless of where it might start.”

Recruits take part in live-fire training during a media day at the Reconnaissance Battalion, as the German army showcases its new six-month basic training program designed to prepare soldiers for homeland defence and NATO operations, in Ahlen, Germany, November 13, 2025. REUTERS/Leon Kuegeler TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

At a higher level, the plan is the clearest manifestation to date of what its authors call an “all-of-society” approach to war. This blurring of the line between the civilian and military realms marks a return to a Cold-War mindset, but updated to account for new threats and hurdles—from Germany’s decrepit infrastructure to inadequate legislation and a smaller military—that didn’t exist at the time.

German officials have said they expect Russia will be ready and willing to attack NATO in 2029. But a string of spying incidents, sabotage attacks and airspace intrusion in Europe, many of them attributed to Moscow by Western intelligence, suggest it could be preparing to pounce sooner.

Analysts also think that a possible armistice in Ukraine, which the U.S. is pushing for this week, could free up time and resources for Russia to prepare a move against NATO members in Europe.

If they succeed in boosting Europe’s resilience, the planners think they cannot just ensure victory, but also make war less likely.

“The goal is to prevent war by making it clear to our enemies that if they attack us, they won’t be successful,” said a senior military officer and one of the earliest authors of the plan, known in military circles as OPLAN DEU.

The magnitude of the shift now required was on display this autumn, somewhere in the east-German countryside.

There, the defense contractor Rheinmetall set up an overnight field camp for 500 soldiers, with dormitories, 48 shower cabins, five gas stations, a field kitchen, drone surveillance and armed guards screened for Russian and Chinese influence. It was built in 14 days and dismantled in seven.

“Picture building a small town from nothing and dismantling it in just a few days,” said Marc Lemmermann, head of sales at Rheinmetall’s logistics business.

Rheinmettall recently signed a €260 million deal to resupply German and NATO troops, part of the military’s efforts to incorporate more of the private sector into the plan.

The autumn operation exposed flaws too: The land couldn’t accommodate all the vehicles, said Lemmermann, and it consisted of noncontiguous plots, forcing Rheinmetall to bus soldiers to and fro. A previous dress rehearsal highlighted the need for a new traffic light at a specific location to alleviate gridlock when military convoys move across the country.

Such lessons are continuously incorporated into OPLAN and its annexes. The document, housed on the military’s air-gapped “red network,” is now in its second iteration.

Some of the biggest obstacles facing Germany’s military planners are intangible: ponderous procurement rules, onerous data protection laws, and other regulations forged in a more peaceful era.

Executing the plan requires rewiring mentalities, erasing almost a generation’s worth of habits.

“We must relearn what we unlearnt,” said Nils Schmid, deputy defense minister. “We have to drag people back from retirement to tell us how we did it back then.”

A troubling accident

A stretch of road on the A44 federal highway between the villages of Steinhausen and Brenken, in western Germany, offers a metaphor for how Europe lowered its guard in the past four decades of peace—and what it would take to raise it again.

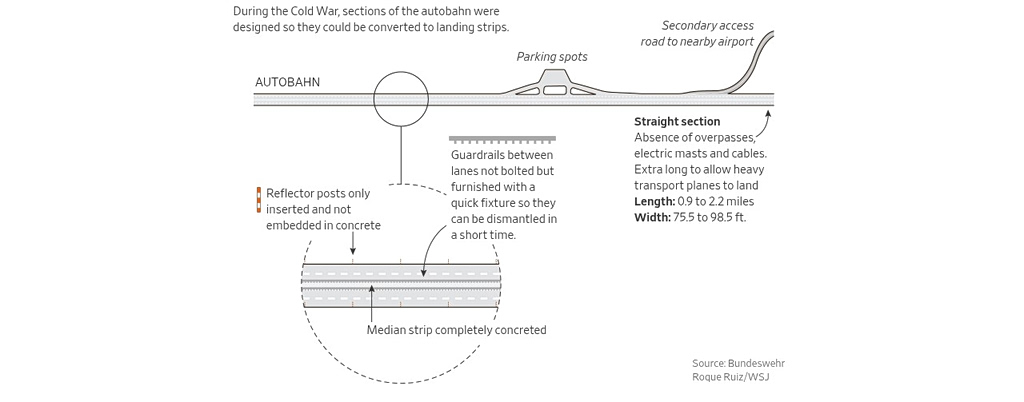

Unlike elsewhere on the autobahn, the median strip on this 3.5-mile section isn’t grassy but solid tarmac. The rest areas are unusually large and oddly shaped. There are no overpasses or power cables in sight.

Dozens such sections were built during the Cold War for use as emergency landing strips. Kerosene tanks were buried underneath the parking areas. The guardrails could be unclicked and a mobile air traffic tower set up in minutes.

So-called dual-use infrastructure was the norm in Germany during the Cold War. Much like mandatory conscription meant civilian and military life were intimately connected, highways, bridges, train stations and ports were designed to serve as military assets if needed.

Then the Cold War ended, as did the need for dual-use infrastructure. Tunnels and bridges built after that were often too narrow or flimsy to accommodate convoys. In 2009, Berlin dropped requirements for signs showing the military vehicles roads could support.

Recruits participate in a training drill during a media day at the Reconnaissance Battalion, as the German army showcases its new six-month basic training program designed to prepare soldiers for homeland defence and NATO operations, in Ahlen, Germany, November 13, 2025. REUTERS/Leon Kuegeler

Even Cold War-era infrastructure isn’t always usable. Berlin estimates 20% of highways and over a quarter of highway bridges need repairs due to chronic underinvestment. Germany’s North Sea and Baltic Sea harbors need work worth €15 billion, including €3 billion for dual-use upgrades such as dock reinforcements, according to the federation of German seaports.

Such patchiness would limit the military’s freedom of movement in case of war. Chokepoints on the military’s mobility map are among the most closely guarded secrets of the blueprint.

“This is leading to detours, delays and is putting lives at risk,” said Jannik Hartmann, associate fellow at the NATO defense college in Rome and an expert in military mobility.

A recent, little-publicized but consequential incident underlines the problem.

On the night of Feb. 25, 2024, the “Rapida,” a Dutch-flagged cargo ship, rammed a railway bridge over the Hunte river in northwestern Germany, shutting down railway traffic.

Railway operator Deutsche Bahn erected a temporary bridge that opened two months later, only to be rammed by another ship in July, interrupting rail traffic again for another month.

Though they only made the local news, the incidents sent NATO scrambling. The reason: The bridge sat on the sole railway link serving the North Sea port of Nordenham, the only terminal in Northern Europe licensed at the time to handle all munitions shipments to Ukraine.

In neither case did security officials find signs of foul play.

Still, ammunition supplies were choked for weeks and some of the cargo had to be reloaded back onto ships. The top U.S. military command in Europe was forced to move shipments to a Polish port, according to a Department of Defense report to Congress.

“Many ports only have one rail route to the hinterland,” said Holger Banik, CEO of Niedersachsen Ports, which owns several ports in Lower Saxony. “This is a weakness.”

In the short term, improving resilience means making the most of the existing road and rail networks. Longer term, Berlin aims to spend €166 billion by 2029 on infrastructure, including more than €100 billion on the long-neglected railways, and give priority to dual-use infrastructure.

Things go off script

The yearslong effort to make Germany war-ready again began days after Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when German Chancellor Olaf Scholz unveiled a €100 billion rearmament fund, hailing the decision a zeitenwende, or an “epochal change.”

Later that year, the German military, known as the bundeswehr, created a Territorial Command to lead all homeland operations and tasked its commander, Lieutenant General André Bodemann, a veteran of Kosovo and Afghanistan, with drafting OPLAN.

In a war with Russia, Germany would no longer be a front line state but a staging ground. On top of a degraded infrastructure, it would have to contend with a shrunken military and new threats such as drones.

“Refugees and reinforcements would be pouring in from opposite directions. The flows would need channeling, which the bundeswehr alone can’t do, especially while it’s fighting,” said Claudia Major, head of trans-Atlantic security initiatives at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

This means the military would need to join with the private sector and civilian organizations on a scale it hadn’t done before.

By March of last year, drawing on feedback from an expanding circle of ministries, government agencies and local authorities, Bodemann’s team had completed the plan‘s first iteration.

The time had come to put it in action.

While the new Merz government was trumpeting a €500 billion defense spending plan and a return to conscription this year, the bundeswehr was working under the radar, briefing hospitals, the police and disaster relief agencies, striking agreements with states and the autobahn operator and drawing transit routes for military convoys.

In late September, a military exercise dubbed Red Storm Bravo took place in the northern city-state of Hamburg to rehearse cooperation between the bundeswehr and the police, firefighters and civil protection units.

The scenario was a miniature OPLAN in action: 500 NATO troops would land in the port to form a convoy of 65 vehicles headed eastward through the city. They would have to fend off attempts to block the port, drone attacks and protests.

Disembarking at sunset amid the scent of overripe bananas wafting from a nearby fruit warehouse, the camouflaged soldiers assembled silently on the dock, helicopters circling overhead. Shortly before midnight, the convoy departed for the city.

Then things began to go off-script.

A convoy always moves as a block: Once it crosses an intersection, it doesn’t stop, whatever the color of the traffic light. No civilian vehicle should be able to insert itself into it.

Yet as the column rolled through the checkpoint, officers on the sidelines bristled at the long gaps between vehicles. Later on, a black drone buzzing overhead caused a brief commotion before someone radioed in confirmation that it was the bundeswehr’s.

Then, protesters jumped from bushes and glued themselves to the tarmac ahead of the vehicles. The incident was part of the drill and the demonstrators were reservists.

Soldiers weren’t allowed to intervene. The police, which were, turned out not to have the solvents needed to unglue the mock protesters.

It took two hours for the vehicles to restart. By then, it was early morning and the convoy had traveled all of 6 miles.

Surging sabotage

The inadequacies of peacetime legislation have also made it harder for Germany to protect itself against sabotage—one of the biggest threats facing OPLAN.

Such sabotage is already happening. Scores of attacks, from arson to vandalized cables, have targeted the railway system in recent years. In October, a Munich court jailed a man for planning to sabotage military installations and railway infrastructure on behalf of Russia.

This week, Poland said Russia was behind an explosion that damaged railway tracks in the country’s east.

Germany’s domestic intelligence agencies said it conducted almost 10,000 employee background checks for critical infrastructure operators last year alone.

“If Germany is going to be NATO’s hub, then as the enemy, I’d want to target that: block the ports, take down the power, disrupt the railways,” said Paul Strobel, head of public affairs for Quantum Systems, a Peter Thiel-backed maker of surveillance drones that is in talks with the bundeswehr about providing convoy and infrastructure protection for OPLAN.

Quantum Systems, one of Germany’s largest and most successful defense startups, has delivered hundreds of drones to Moldova and Romania and it has thousands flying in Ukraine everyday, said Strobel. Yet so far it has sold only 14 to the bundeswehr.

One of the main culprits: Antiquated legislation. Drones sold to the German military can’t be flown over built-up areas. The law also requires them to have position lights.

“Which makes sense in civilian use but defeats the purpose in a military setting,” said Strobel.

The bundeswehr is sanguine about its progress. “Considering that we started with a blank page in early 2023, We are very happy with where we are today,” said the officer and OPLAN co-author. “This is a very sophisticated product.”

Yet as the recent stress tests showed, there is still work to do for the plan and reality to line up. The biggest uncertainty facing the planners is how much time they have.

Given the steep rise in sabotage, cyberattacks and airspace intrusions, the difference between peace and war is looking increasingly fuzzy.

“The threats are real,” Chancellor Friedrich Merz told business leaders in September. “We’re not at war, but we no longer live in peacetime.”

Write to Bertrand Benoit at bertrand.benoit@wsj.com