Giorgio Armani , the designer and business mogul who brought subtle Italian luxury to the world stage and conquered Hollywood, has died at age 91.

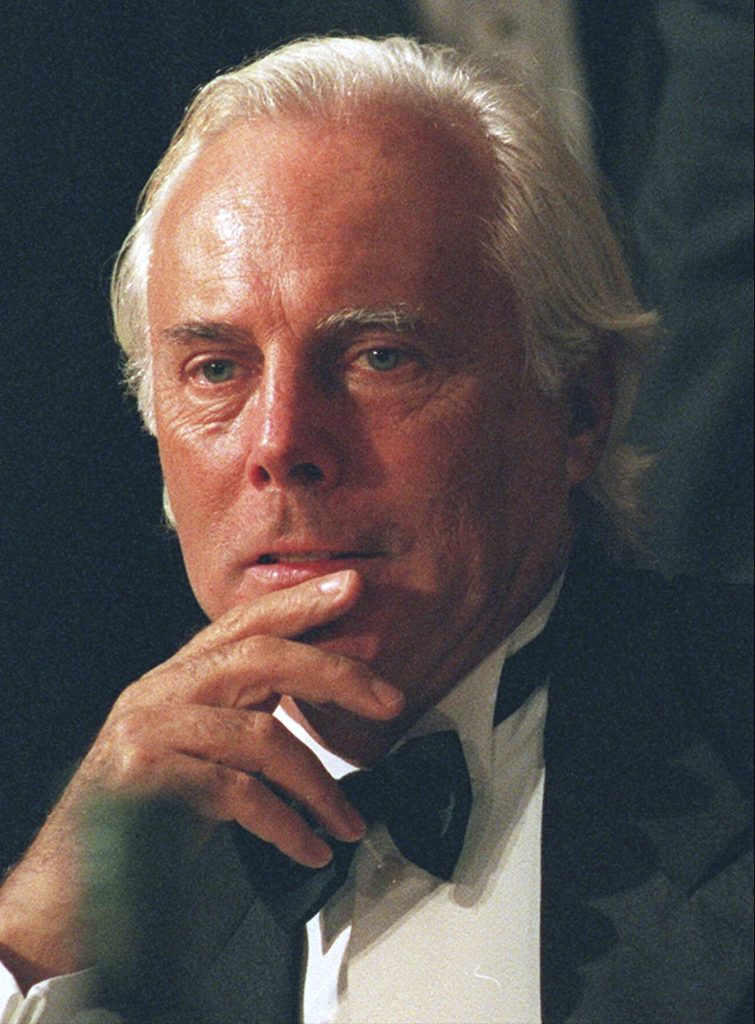

FILE – Italian fashion designer Giorgio Armani, at the National Italian American Foundation, Oct. 29, 1994 in Washington. (AP Photo/Greg Gibson, file)

A news release from his namesake brand said “he worked until his final days, dedicating himself to the company, the collections, and the many ongoing and future projects.”

During his years at the helm of his multibillion-dollar Milan brand, he remained steadfastly independent in a fashion landscape dominated increasingly by conglomerates.

Although he disliked the moniker , Armani was often called “the king of fashion.” In an interview with The Wall Street Journal in 2024, he insisted that the secret to success was his humble, consistent work ethic, not his larger-than-life public persona. Yes, he owned a deep-green superyacht and homes in New York, Milan, Pantelleria, Antigua, Paris, St. Moritz, St. Tropez, Forte dei Marmi and Broni, but he still showed up at the office every morning and ruled his sprawling business empire with a firm hand.

Armani, who called himself a “designer-businessman,” was the sole shareholder of his privately held company at the time of his death. In 2023, the company’s revenue was $2.6 billion worldwide across men’s and women’s lines, the Emporio Armani diffusion line, Armani Privé haute couture, interiors, dozens of restaurants, 2,500 retail stores, fragrances and a cult-classic beauty line. Whether it took the form of relaxed suiting, “Liquid Silk” face makeup or cosseted interior design, his work whispered refinement in the most hushed register possible.

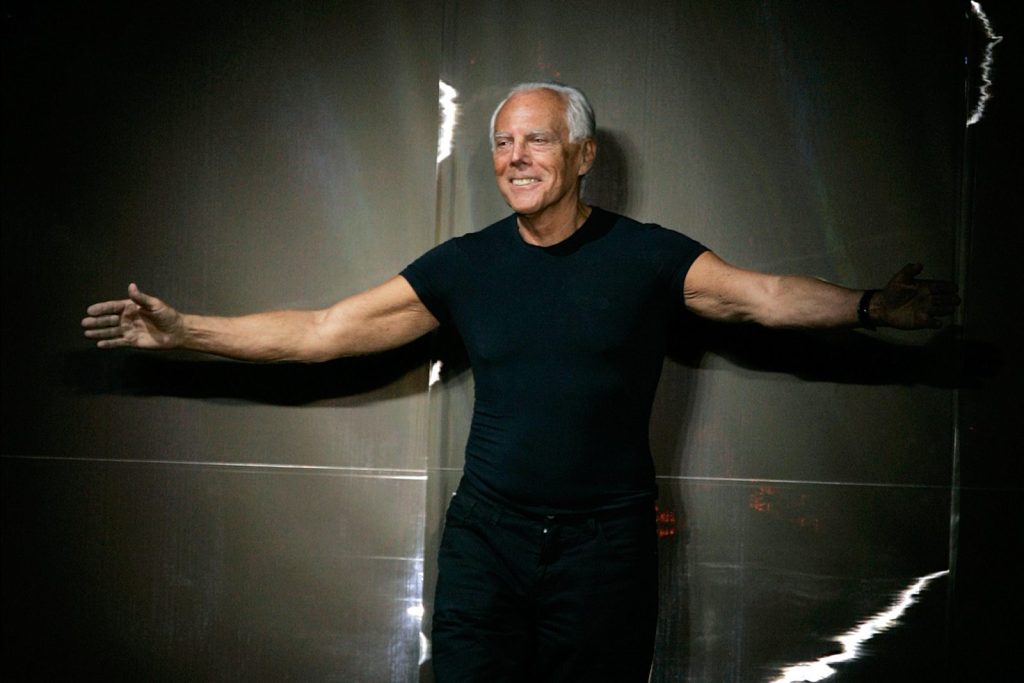

Giorgio Armani acknowledges the applause of the audience after presenting the Emporio Armani menswear Fall-Winter 2023-24 collection, in Milan, Italy, Saturday, Jan. 14, 2023. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

His stylistic innovations included an emphasis on neutral, in-between colors, soft shoulders, and a more relaxed approach to evening looks for men and women. He often drew inspiration from Asian culture in his work; for example, Akira Kurosawa’s 1980 film “Kagemusha” inspired his fall 1981 “Samurai” collection.

“I love that he has this balance of softness and power,” said Armani’s fellow designer Michael Kors at his last New York runway show in 2024.

The designer’s quiet touch made an indelible mark in flashy Hollywood. Armani first became a household name when he designed Richard Gere’s low-key suits in the 1980 movie “American Gigolo.” From the 1980s until recent years, he was a go-to designer for unshowy red-carpet looks, dressing Oscar winners from Jodie Foster to Cate Blanchett.

In 2024, Armani stressed the “extremely important” role independence played in his impact. “It’s not a question of pride,” he said. “It’s about getting things done. When I have an idea, I want to see it through to the end.”

From left, actress Zoe Saldana, designer Giorgio Armani and singer Solange Knowles attend the ‘Armani 5th Avenue’ store opening party, Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2009 in New York. (AP Photo/Evan Agostini)

While Armani had no children or spouse, he set up a trust in 2016 that laid out his plans for his company, including a charitable foundation and details for how an eventual public stock listing or an acquisition should be handled. He worked with a close circle of collaborators, including his sister, Rosanna, who is on the board of directors; his niece Silvana, who is the head of women’s design; his niece Roberta, the head of VIP and entertainment relations; and his nephew Andrea Camerana, the sustainability managing director. His right-hand man and close friend was the head of menswear, Pantaleo (Leo) Dell’Orco, who came out to take a bow with Armani in recent years.

Baptism by fire

Born in the northern Italian town of Piacenza on July 11, 1934, Armani was the middle child of three siblings, between older brother, Sergio, and younger sister, Rosanna. His father worked for a transportation company while his mother took care of the family.

Armani described his childhood, marked by a fascist regime and World War II, as hardscrabble. At 9 years old, he was standing outside a local movie theater, looking at a poster for “Snow White,” when one of his friends came across an unexploded shell of gunpowder. It caught fire, and the young Armani burst into flames. He said that he shut his eyes, only to open them 20 days later in the hospital. While there, he was placed in a vat of pure alcohol to remove the dead skin. His only lasting scar was on his foot, where his shoe melted into his flesh.

The violent burn of his youth contributed to Armani’s desire to become a doctor. He attended medical school in Milan for three years before dropping out to fulfill his compulsory military service. But after the army, Armani’s latent creativity was stirred, and he dropped the dream of a career in medicine.

The young Armani began working as an assistant architect, designing interiors and displays for the La Rinascente department store in Milan. He moved into menswear, working for a time for Hitman, a company owned by Nino Cerruti, and freelancing for other brands.

In the mid-1960s, Armani met his longtime life and business partner, Sergio Galeotti. A Tuscan architectural draftsman 10 years his junior, Galeotti became a galvanizing force for Armani and persuaded him to start his own business in 1975. Galeotti, 30, took care of the business, while Armani, 40, was the creative force and face of the brand.

“He woke me up from a sort of torpor, from the little life in which I was living,” Armani told The Wall Street Journal in 2012.

In the first 10 years of the company, Galeotti and Armani made Giorgio Armani SpA a destination for a certain type of loose, chic menswear and womenswear—tailoring without rigidity, liberal use of a neutral palette and natural fibers. On Wall Street, the Armani “power suit” took hold and became the greige standard for a new class of businesspeople.

In 1985, Galeotti died from an AIDS-related illness, a loss Armani mourned until the end of his life. Armani credits Galeotti’s death as a catalyst for him to give priority to the company’s independence and to continually take business matters into his own hands.

After his partner was gone, Armani became a mogul in addition to a designer.

From Corso Venezia to Rodeo Drive

In 1979, movie director Paul Schrader visited Milan with actor John Travolta, who was slated to play the role of Julian Kaye in “American Gigolo.” Schrader perused Armani’s spring collection of relaxed separates and earth-toned suits, and decided it was perfect for the film. Travolta was eventually replaced by Richard Gere, and when the film came out in 1980, it was a hit for everyone involved, including the Italian designer.

“That’s also when I first visited Hollywood, and my first time on a movie set,” Armani told System magazine in 2024. “Seeing a film being made was a dream come true for a cinephile like me.”

By 1982, when Armani was photographed for the cover of Time magazine (with the cover line “Giorgio’s Gorgeous Style”), his name had become synonymous with sophistication in the U.S., mostly thanks to his Hollywood bona fides.

Armani would go on to work on costumes for over 250 films, including the Prohibition-era period pieces for “The Untouchables” in 1987, Jodie Foster’s shimmery, sharply cut look in the 2013 sci-fi “Elysium” and Christian Bale’s luxe suits in the 2008 movie “The Dark Knight.”

As effective as Armani’s work on screen was his prowess for dressing stars for the red carpet. Before his Hollywood breakout, Armani admitted how Diane Keaton dressed like a real person in “Annie Hall” in 1977, so he dressed her in a similarly eclectic look for the following year’s Oscar awards. undefined undefined In 1990, Women’s Wear Daily dubbed that year’s Oscars “The Armani Awards” when the designer dressed many actors including Tom Cruise, Rosie Perez, Michelle Pfeiffer and Julia Roberts. By then, Armani had already set up a VIP dressing office on Rodeo Drive—a novelty at the time—to service his new celebrity clientele.

“I thought a more natural and personal style was needed off-screen, to be more closely aligned with actors’ on-screen work,” Armani told System magazine of his Hollywood vision.

The self-sufficient sovereign

In his later years, Armani was admired as much for his longevity in the fashion business as he was for his independence, as luxury conglomerates like LVMH (formed by the merger of Moët Hennessy and Louis Vuitton) and Kering gathered steam. Meanwhile, many of his compatriots were snapped up: Tapestry owns Versace; Kering ’s holdings include Gucci and Bottega Veneta; LVMH owns Fendi and Bulgari.

Although Armani said in 2024 that representatives for conglomerates continued to make overtures to him about an acquisition—even more as he grew older—he always told them the same thing: “It’s not the right time.”

Even after turning 90, Armani showed no signs of stopping. He continued to put on fashion shows in Milan and Paris for lines including Giorgio Armani, Emporio Armani and his couture Armani Privé line, many of them at his custom-built circular “teatro,” with its luxurious padded seats. He celebrated 50 years of his company with a 93-look fashion show in New York, and opened a 12-floor building on Madison Avenue, complete with clothing and home boutiques, a restaurant and 10 residences, which started at $21.5 million. He saved one for himself, so he could have pads on both the Upper West Side and the Upper East Side in a city he rarely visited.

While Armani continued to quietly innovate into the latter part of his life, a new generation of fans sought out his vintage pieces from the ’80s and ’90s. Streetwear retailer Kith and Swedish brand Our Legacy collaborated with the brand on youth-focused collections, and Australian tailor Patrick Johnson said on a podcast that Armani was always his No. 1 inspiration.

Now, his heirs including family members Rosanna, Silvana, Roberta and Andrea, as well as right-hand man Leo Dell’Orco, will be faced with whether to succumb to the inevitable offers from potential buyers, will make the company public, or continue on its current path.

Italian fashion designer Giorgio Armani poses with models at the end of his men’s Spring-Summer 2014 fashion show, part of the Milan Fashion Week, unveiled in Milan, Italy, Tuesday, June 25, 2013. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

One question is whether the next chapter will involve a new creative director. If so, the successor will have a towering legacy to live up to.

“Humbleness,” said Armani when asked in 2024 which quality he’d like to impart to his collaborators before he left. “Sometimes people in this business have strong egos, and it’s important to remain modest.”

Write to Rory Satran at rory.satran@wsj.com