On a blazing hot day in November, Raibel Palacio and three neighborhood friends boarded a flight at Cuba’s Varadero beach resort, taking selfies and chattering in excitement. They had a job offer that promised a way out of the island’s misery .

A few weeks later, Palacio was killed by a drone as he tried to tie a tourniquet to staunch the bleeding from a leg wound on the freezing front lines of Ukraine , said Danelia Herrera , his mother.

“Cubans are cannon fodder and they will kill them all,” she said, weeping in her home, a wooden shack on the outskirts of Havana.

The four young men are part of a wave of Cubans who enlisted in the Russian army , lured by salaries in the region of $2,000, far higher than they would be able to earn at home, where the average monthly wage is less than $20 and people rely on government rations or remittances from relatives overseas to get by.

Ambassador Ruslan Spirin , Ukraine’s special representative to Latin America and the Caribbean, said the government believes that about 400 Cubans are fighting in the country. “We take it seriously,” he said.

Others think the numbers go higher. Maryan Zablotskyi, a member of the Ukrainian parliament who has studied the issue, estimates that between 1,500 and 3,000 Cubans have enlisted as the island’s state-controlled economy crumbles .

Russia has also recruited fighters from the Central African Republic, Serbia, Nepal and Syria, according to Ukrainian authorities, to prop up its war effort. On the opposing side, the number of volunteers, initially numbering thousands, including U.S. military veterans , has dropped off as the war drags toward a third year.

The Cubans are one of the largest contingents, motivated by the implosion of Cuba’s economy, which is ossifying under a die-hard Communist government reluctant to open up to private and foreign investment after decades of mismanagement, and the impact of U.S. economic sanctions.

For military recruiters working for Russia, Cuba’s worsening poverty makes for easy pickings as Moscow attempts to fill the holes in its front lines, security experts say.

Deteriorating living conditions and an increasing sense of hopelessness among working-age Cubans have sparked an unprecedented wave of emigration. More than 500,000 Cubans, or about 5% of the country’s population, have left for the U.S. in the last two years, according to U.S. government data, while back home on the island, shortages of fuel, food and medicine are spreading. Power outages are frequent amid scorching heat.

Palacio was the first Cuban recruit whose death in combat last month was confirmed by his family. It was initially reported by the Spanish-language Univision network in Miami.

“After five months, they were going to give him a Russian passport and citizenship for me, his mother and our two daughters,” said Melisa Flores , Palacio’s wife. She hoped to escape poverty to a new life far from the shack she shared with her husband, which floods when it rains. Sometimes the family had to rely on neighbors for food.

In Russia, she thought things would be different, she said.

As word spread on WhatsApp chats across the Caribbean island, “everybody in the neighborhood was talking about going to Russia to work,” said Mario Velázquez . His teenage son, Andorf, an unemployed mason who lived in Havana, left for Moscow in July. Two recruiters, a Russian woman named Elena and a Cuban named Dayana, promised Andorf a bright future in Russia, Velázquez said.

The Cuban government said in September that it dismantled a recruitment ring luring Cubans to fight in Ukraine. The island’s Communist regime, historically wary of invasion by the U.S., bans mercenary recruitment. Prosecutors said they detained 17 people who could face prison sentences of up to 30 years or even the death penalty.

Ukrainian officials are skeptical about the impact of the Russian recruitment drive in Cuba.

“A few hundred Cubans won’t make a difference on the battlefield,” said one senior Ukrainian security official, though he noted that Russia’s aim in recruiting them was likely to draw Cuba deeper into the war on the Russian side.

Russia’s Embassy in Havana didn’t reply to requests for comment. Neither did Cuban officials in Washington and Havana.

As Russia expands its recruitment across a belt of impoverished countries, from the Caribbean and across Africa to parts of Asia, it helps Russian President Vladimir Putin push back what would be a deeply unpopular order to call up more Russians to fight until after a presidential election next month. Though he is expected to win another six-year term, the margin of his victory is important to the Kremlin as it tries to demonstrate continuing support for the war.

In a bid to increase the number of soldiers in its military, Putin signed a decree in January allowing foreigners who serve in Russia’s military for a year to obtain Russian citizenship for themselves, their spouses, children and parents.

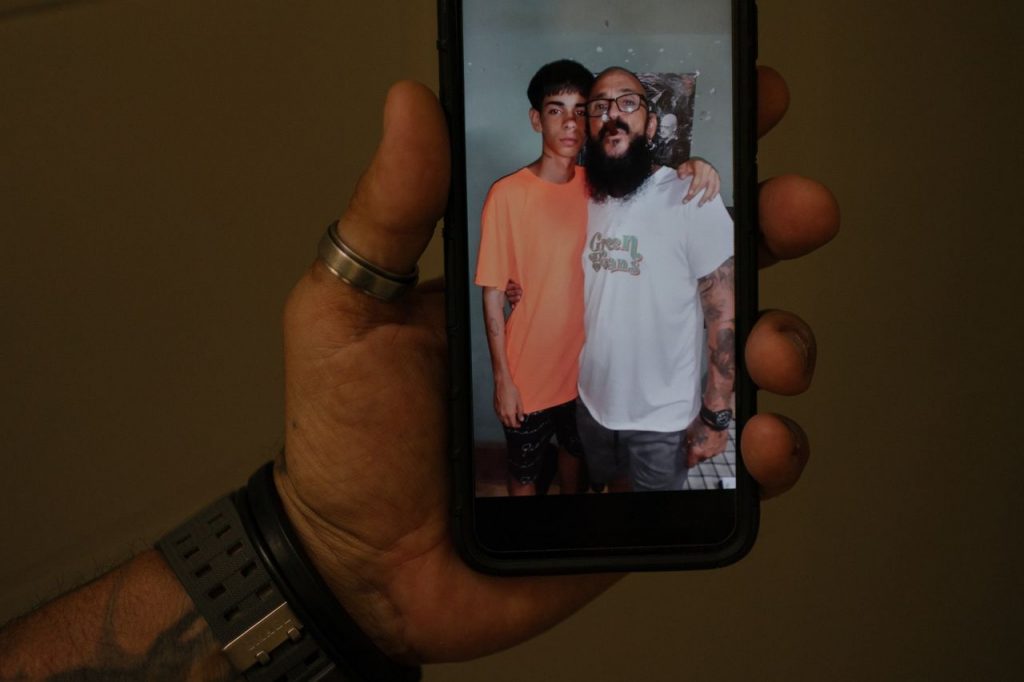

Mario Velázquez shows a photo of him and his son Andorf. PHOTO: LUIS ANTONIO ROJAS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Russia has waived debt payments to its former Cold War ally and supplied fuel oil to help keep the island’s sputtering power grid going. It has also donated tons of wheat and cooking oil, which are scarce on the island.

Havana has long been one of Moscow’s closest partners. At the height of the Cold War in 1962, the Soviet Union and the U.S. came to the brink of nuclear war after the U.S. discovered Soviet nuclear missiles on the island. From 1975 to 1991, Cuba deployed more than 50,000 soldiers to Angola and Ethiopia in support of Soviet policies.

The Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 transformed the Cuban military, once among the largest and best-armed in Latin America. The military was slashed to some 40,000 soldiers, and is now more focused on managing tourist hotels and growing beans than fighting in foreign wars.

Now the security relationship is picking up again as Russia looks for more troops.

Ukraine has been closely following a parade of high-ranking officials traveling between Moscow and Havana since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, including Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel and his defense minister, Alvaro López Miera , who met with Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu to discuss military cooperation.

“After the visits, we started seeing Cuban mercenaries on the battlefield,” said Spirin, the special envoy.

“They weren’t soldiers or former soldiers,” he said. “They are poor people who don’t have the money to buy airline tickets.”

Knowing the effectiveness of Cuba’s intelligence services, Spirin said, he found it difficult to believe that the government wasn’t aware of the recruitment. “We have informed the Cuban government of our concerns,” he added.

Jose Cohen , a former Cuban intelligence agent who defected in 1994 and now lives in the U.S., said it is impossible that the government doesn’t know of the flow of Cubans going to fight in Ukraine. “Cuba will always say it had nothing to do with it,” he said.

The U.S. has also raised “serious concerns” about the reports of Cubans recruited by Russia, a State Department spokeswoman said. The U.S. has asked Cuba for information on its investigation of the recruitment ring. Cuba hasn’t provided any or made any public comments since the initial announcement in September, the spokeswoman said.

“We have repeatedly warned Cuba not to let its citizens fight in Russia’s war,” the spokeswoman said.

In the industrial city of León in central Mexico, where he now works as a security guard and married a Mexican woman, Velázquez looks at photos on his phone showing his son Andorf, a skinny young man swallowed up in a green camouflage uniform three sizes too big for him over the white-and-blue striped shirt Russian soldiers wear.

Mario Velázquez now lives in León, Mexico, after leaving Cuba. PHOTO: LUIS ANTONIO ROJAS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Aerial view of León, Mexico. PHOTO: LUIS ANTONIO ROJAS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Andorf signed up for what he thought was a work contract to dig trenches and fix destroyed buildings in Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine, but not to fight, said Velázquez.

“It’s a dream that turned into a nightmare,” he said, his voice breaking. He hasn’t been able to talk to his son since September and fears for his life.

In a video recording of Andorf and his friend Alex Vega , the two slightly built young men said they ended up on the front lines in Ukraine after signing contracts in Russian that they couldn’t understand. They warn other Cubans not to follow them.

“There are a lot of Cubans who have disappeared,” Vega said in the recording. “If you are thinking about coming to Russia, don’t.”

Write to José de Córdoba at jose.decordoba@wsj.com