Imagine your 13-year-old signs up for TikTok and, while scrolling through videos, lingers on footage of explosions, rockets and terrified families from the war in Israel and Gaza.

Your child doesn’t search or follow any accounts. But just pausing on videos about the conflict leads the app to start serving up more war-related content.

That’s what happened to a handful of automated accounts, or bots, that The Wall Street Journal created to understand what TikTok shows young users about the conflict. Those bots, registered as 13-year-old users, browsed TikTok’s For You feed, the highly personalized, never-ending stream of content curated by the algorithm.

Within hours after signing up, TikTok began serving someaccounts highly polarized content, reflecting often extreme pro-Palestinian or pro-Israel positions about the conflict. Many stoked fear.

Dozens of these end-of-the-world or alarmist videos were shown more than 150 times across eight accounts registered by the Journal as 13-year-old users. Some urged viewers to prepare for an attack. “If you don’t own a gun, buy one,” one warns.

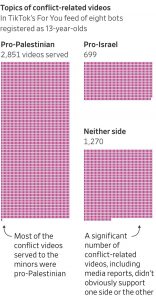

While a sizable number of the war-related videos served to the Journal’s accounts supported one side or the other in the conflict, a majority supported the Palestinian view.

Research shows that many young people increasingly get their news from TikTok. In the Journal’s experiment, the app served up some videos posted by Western and Arab news organizations. But they were a minority—about one in seven of the conflict videos. The rest were posted largely by influencers, activists, anonymous accounts, newshounds and the Israeli government.

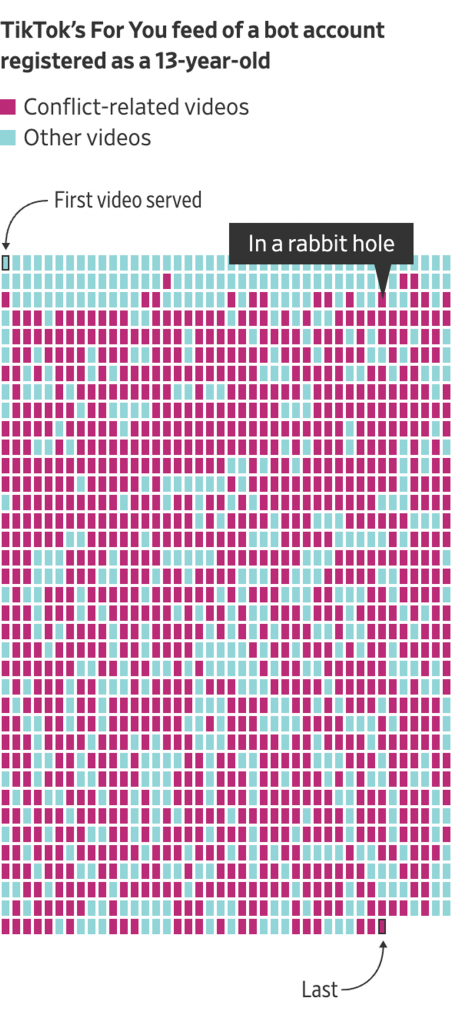

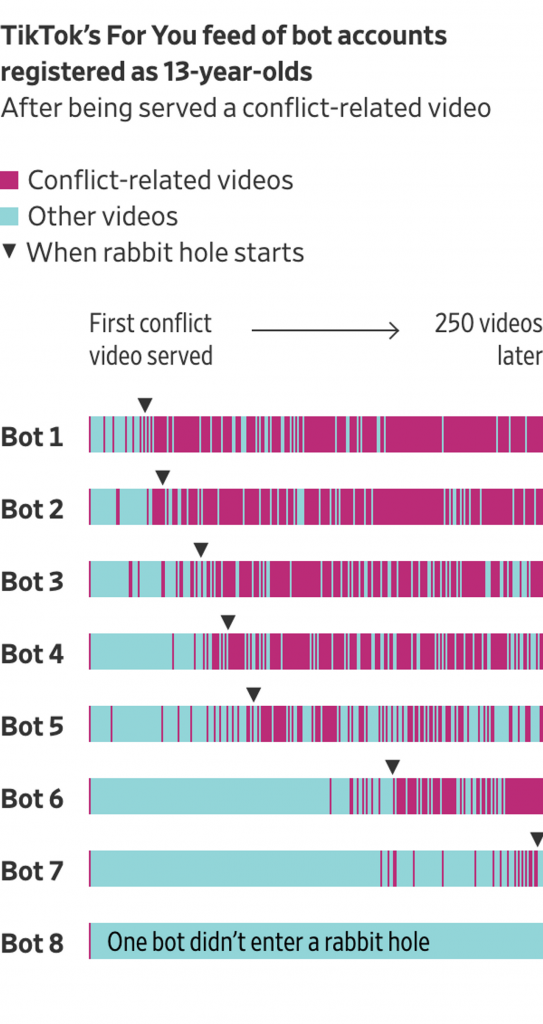

Some of the accounts quickly fell into so-called rabbit holes, where half or more of the videos served to them were related to the war. On one account, the first conflict-related video came up as the 58th video TikTok served. After lingering on several videos like it, the account was soon inundated with videos of protests, suffering children and descriptions of death.

TikTok determines what content to serve to users with a sophisticated algorithm keyed on what its users watch, rather than basing it mostly on what accounts users follow or the content they subscribe to, like some other social media. This makes it challenging for researchers and parents to understand the experiences young people have on the popular app.

The bots the Journal used provide a glimpse of the content young users may encounter on the app, as well as a test of the guardrails TikTok sets for what videos it shows them—and in what volume.

A spokeswoman for TikTok said the Journal’s experiment “in no way reflects the behaviors or experiences of real teens on TikTok.”

“Real people like, share and search for content, favorite videos, post comments, follow others, and enjoy a wide-range of content on TikTok,” the spokeswoman said in a written statement.

TikTok said that between Oct. 7 and Nov. 30, it removed more than 6.9 million videos with shocking and graphic content, 2.4 million promoting violent and hateful organizations and individuals, 2 million with hate speech and 131,000 with harmful misinformation.

The Journal set one of the accounts to a restricted mode, which TikTok says limits content that may not be suitable for all audiences. That didn’t stop the app from inundating the user with war. Soon after signing up, the account’s feed was almost entirely dominated by vivid images and descriptions of the conflict, which began on Oct. 7, when Hamas militants crossed the border and killed about 1,200 people in Israel.

TikTok’s algorithms are uniquely powerful at picking up which videos get users’ attention and then feeding them the most engaging content on the topic. “You don’t have to doomscroll—you can just sit and watch and let the platform do the rest,” said Emerson Brooking, who studies digital platforms as a resident senior fellow at the Digital Forensic Research Lab at the Atlantic Council, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.

Most of the videos TikTok served the Journal’s accounts don’t appear to violate the app’s community policies banning promotion of terrorist groups or content that is gory or extremely violent. But hundreds of the videos described death or showed terrified children. Many of them are difficult to verify.

War-related videos served at least 14 times to the bots are now marked as sensitive and sometimes blocked from being shown to younger users. Hundreds of others were later unavailable on TikTok, either because TikTok removed them or the poster took them down or made them private—but not before they were served to the Journal’s accounts.

“It’s not normal for any adult to see this amount of content, but for kids, it’s like driving 100 miles an hour without any speed bumps, being constantly inundated with demoralizing, emotional content,” said Larissa May, founder of #HalfTheStory, an education nonprofit focused on adolescent digital well-being and the influence of technology on mental health.

TikTok said its family-control features let parents filter out keywords and restrict searches for a child’s account.It also says that since Oct. 7 it has prevented teen accounts from viewing over 1 million videos containing violence or graphic content.

Of the Journal’s eight test accounts, five fell into rabbit holes within 100 videos after the first conflict-related video appeared. (A bot is considered to be in a rabbit hole if more than half of videos—a rolling average that includes the previous 25 and next 25 videos—are conflict-related.) Two others hit that point within the first 250 videos.

Similarly to other social-media platforms, much of the war content TikTok served the accounts was pro-Palestinian—accounting for 59% of the more than 4,800 videos served to the bots that the Journal reviewed and deemed relevant to the conflict or war. Some 15% of those shown were pro-Israel.

The spokeswoman for TikTok said the platform doesn’t promote one side of an issue over another.

TikTok served the Journal’s accounts videos from one pro-Palestinian account more than 90 times. The account, @free.palestine1160, has no bio but includes a link to a Qatar-based charity’s fundraising page for emergency relief and shelter in Gaza.

The charity didn’t respond to a request for comment.

While pro-Palestinian content was more common, the feeds were also interspersed with pro-Israel videos, including dozens from the Israeli military and government.

“I saw little kids who were beheaded. We didn’t know which head belonged to which kid,” an aid worker said in one video TikTok served the accounts. After being seen by a Journal bot, the video was later removed.

Hundreds of the videos TikTok showed the Journal accounts evoke death without showing it directly. One video described mass graves in Gaza and watching “the bodies of children being stored in ice-cream trucks because the morgues are so full of the dead.”

Content can still be traumatizing to children even if it isn’t visually graphic.

“No child should be watching video after video of kids in war for hours a day,” May said. “Being hit with this content day after day starts to prune kids’ ability to emote and process what they are seeing, and they just start being apathetic.”

—John West contributed to this article.

Sources:

@_emanboost, @theorysphere7, @uncovering_yt, @al_1713, @peace_and_love_foreverrr, @yosephhaddad, @learnarabic_with_naseem, @peace_and_love_foreverrr, @dody_do, @almayadeentv, @free.palestine1160, @devotedly.yours, @yourfavoriteguy, @falasteeenia, @idf, @israelinuk, @user6671134811741, @cbcnews, @hannahewestberg, @jessicamirandaelter, @nhintaodayne

Write to Sam Schechner at Sam.Schechner@wsj.com, Rob Barry at Rob.Barry@wsj.com, Georgia Wells at georgia.wells@wsj.com, Jason French at jason.french@wsj.com, Brian Whitton at brian.whitton@wsj.com and Kara Dapena at kara.dapena@wsj.com