HASAKAH, Syria—In a wing of the notorious Al Sina prison in northeastern Syria, where some of the world’s most dangerous inmates are held, guards wearing balaclavas stood along a corridor lined with cells. A prisoner pressed his face to a small, square hole in one of the cell doors. Behind him, some 20 other prisoners in brown jumpsuits sat barefoot on the floor.

“Is Biden still the U.S. president?” he asked a visiting journalist. The prisoner, a British Islamic State member, didn’t get an answer.

Visiting journalists are instructed not to answer any questions from inmates seeking even mundane information. Guards are also prohibited from speaking to them about current events.

Inmates at Al Sina don’t even know who the president of Syria is—that dictator Bashar al-Assad is gone and former jihadists once linked to al Qaeda and Islamic State are governing Syria. The less they know, the more secure are Al Sina prison and Syria, say prison officials.

The high-walled prison is part of a network in the region of more than two dozen detention facilities holding Islamic State members and their families since a U.S.-backed coalition led by Kurdish militias defeated the group in 2019. They are home to the largest population of Islamic State prisoners in the world, and those considered the most dangerous are held at Al Sina.

U.S. military commanders and regional security experts have warned that the detainee population is an unresolved security dilemma threatening a new and uncertain Syria. Islamic State has targeted the camps and prisons with propaganda and messages to stir unrest—part of the reason the most dangerous prisoners held in Al Sina are kept under an information blackout.

Escape attempts from the largest detention camp in northeast Syria, Al Hol, have increased this year. Sleeper cells are active inside the camps and weapons have been confiscated during searches by Kurdish and U.S. forces, according to camp administrators, Kurdish counterterrorism and military officials, U.N. investigators and interviews with detainees.

“It’s something disastrous that we can clearly see happening in front of our faces, yet we’re still struggling to do anything about it,” said Colin Clarke, executive director of the Soufan Center, a nonprofit research center focusing on counterterrorism. “If ISIS was able to successfully stage some kind of a prison break or detention center break, it would be disastrous.”

The fall of the Assad regime last year has only deepened concerns. The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces who guard the archipelago of prisons and detention camps are under pressure from Syria’s new rulers and their backers in Turkey.

Al Sina, with its masked guards, maintains tight controls on the flow of information to its inmates. Photography by Moises Saman for WSJ

Authorities want to avoid a repeat of what happened at the Al Sina prison three years ago, when Islamic State militants attacked the facility. That sparked a weeklong battle against American and Kurdish-led forces, which left more than 500 dead, mostly militants. In the chaos, hundreds escaped and potentially re-entered the ranks of Islamic State.

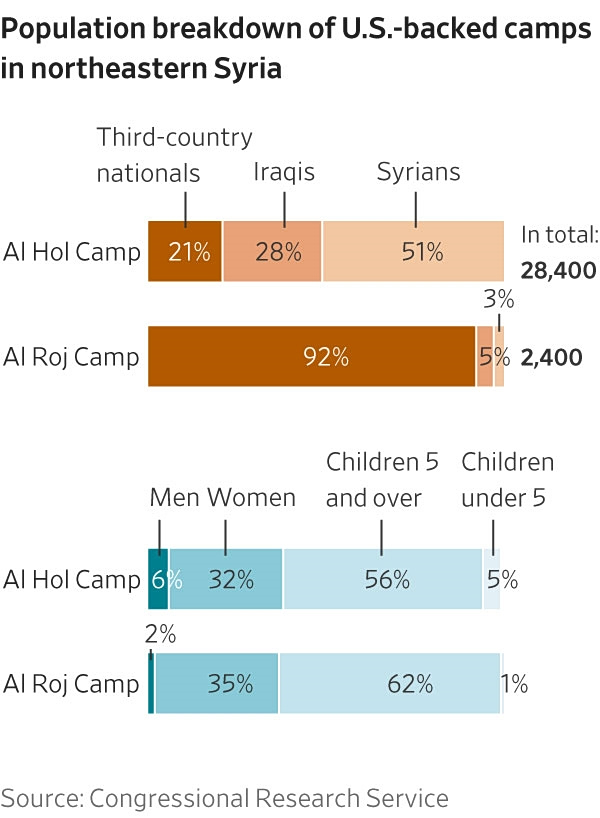

Some 8,400 imprisoned Islamic State militants from 70 countries and roughly 30,000 Islamic State wives, children, radicalized supporters and others accused of ties to the group live in the network of prisons and detention camps. Nearly half the population are foreigners, including Europeans and some Americans. About 60% are children, half of whom are under the age of 12.

The Pentagon’s Central Command has described the inmates at Al Sina as an “ISIS army in detention,” using the acronym that many use to refer to Islamic State.

U.S. intelligence officials, in their annual threat assessment to Congress in March, warned that Islamic State would seek to exploit the end of the Assad regime “to free prisoners to rebuild their ranks.”

Adm. Brad Cooper, the head of Central Command, told a U.N. gathering in late September that Islamic State remains influential in the detainee camps. “As time goes on, these camps are incubators for radicalization,” he said.

The Al Hol detention facility, a dusty and overcrowded complex ringed by barbed-wire fencing, sits about 20 miles east of Al Sina prison near the border with Iraq. It holds mainly women and children—families of Islamic State fighters. A smaller camp, Al Roj, lies to the north.

The U.N. and humanitarian organizations have described the conditions at both camps as inhuman and degrading, citing issues such as inadequate healthcare and instances of violence against women.

The Trump administration this year has cut at least $117 million in U.S. aid to northeast Syria, including at least 15 projects in Al Hol and five in Al Roj, according to the NES NGO Forum, a coalition of aid groups in the region. In July, USAID, the foreign-aid arm of the U.S. government, was closed.

Programs that lost funding included assistance to medical facilities and health-related rehabilitation, as well as providing psychological support and safe spaces for children, said Jihan Hanan, the director of Al Hol. The loss of the programs will make children at the camp more susceptible to radicalization, she added.

The inspector general for the U.S. military’s Syria and Iraq mission against Islamic State reported in August that the USAID cuts and the loss of programs to help youth have “increased tensions in the camp.” The report also found that USAID’s own staff noted that women and children were more vulnerable now to “abuse, exploitation and radicalization.”

The U.N. and European donors have filled in some of the gaps, but it is far from the funding that the U.S. once provided, said Hanan.

“U.S. foreign assistance to the camps will not remain an indefinite responsibility,” a State Department spokesperson said. “The United States has shouldered too much of this burden for too long.”

At their peak, Al Hol and Al Roj housed more than 73,000 people. The population has dropped as detainees have been released or repatriated to their home countries, particularly Iraq. The U.S. government still continues to fund repatriations.

Kurdish and U.S. officials have repeatedly urged countries to take back their nationals, which could eventually allow the detention camps and prisons to shut down. But few governments have done so, fearing that radicalized jihadists could destabilize their countries and spawn political problems at home.

“This problem will only get worse with time,” Cooper said at the U.N. gathering. “Every day without repatriation compounds the risk to all of us.”

The U.S. has repatriated around 50 American citizens since 2016, according to the State Department, including an unaccompanied minor in July. According to some estimates, fewer than 10 U.S. citizens remain in the facilities. The State Department didn’t respond to a request for the precise number.

U.S. commanders are concerned about security at the prisons and camps. Training for the Kurdish guards at the facilities is inconsistent because they are pulled away often to deal with instability elsewhere, the inspector general reported. Kurdish-led forces have clashed with militants backed by the Syrian government and Turkey.

Islamic State has exploited the instability, ramping up attacks this year against the Kurdish-led forces. The group has also sought to take advantage of the fragile political climate and aid cuts by stirring unrest in the detention facilities, said Hanan.

In November 2024, as rebels marched on Damascus, an Islamic State operative infiltrated Al Hol, according to U.N. investigators. He replaced experienced militants with teenage boys, allowing several fighters to escape. He also reactivated the Ansar al-Afifat brigade, which was tasked with gathering intelligence inside the camp and recruiting youths, U.N. investigators said.

“It’s in charge of indoctrinating the kids,” said Hanan. ”It’s going very strong.”

In April, Kurdish-led and American coalition forces raided Al Hol after the security situation inside worsened. Islamic State sleeper cells had attacked the camp’s police, and the offices of some charities were burned. Some cells tried to organize a mass escape attempt. The operation led to 20 arrests and confiscation of three AK-47 rifles, a pistol, hand grenades and homemade bombs.

In November, Kurdish-led and U.S. forces arrested a senior Islamic State leader at Al Hol whom they had been surveilling for days.

Al Hol doesn’t keep its detainees under the strict information blackout that Al Sina imposes. Islamic State has exploited that to spread its propaganda.

The group regularly sends Quranic messages to detainees’ cellphones assuring them that they will be rescued one day. It also gives them updates on its latest operations, saying they were revenge for the detainees’ incarceration. The militants use social media to organize and communicate with sleeper cells and spread propaganda.

In one voice message, listened to by The Wall Street Journal, the group told its followers to rise up, “to engage in jihad and to fight alone if necessary” to help those who are detained.

“Can their souls rest easy, their women and children live in peace, while the women and children of the believers are behind walls?” the message said. “Ignite the war. Draw your swords. Strike blow after blow.”

One detainee, Hussein Saleh, said Islamic State has tried to assassinate him four times for helping Kurdish camp police, branding him a traitor. He now lives in a protected safe zone inside the camp with others who have faced threats from the group.

“There are many killers here because they started believing in Islamic State ideology,” Saleh, 42, said as he sat in front of his tent. “They don’t have money and Islamic State pays them in the camps. They will kill a person for $50.”

Write to Sudarsan Raghavan at sudarsan.raghavan@wsj.com