REVINGEHED, Sweden—Deep in the Scandinavian forest, Elin Forsberg ’s face is planted in the grass, her arms pinned to her back by two soldiers in mock arrest.

The 19-year-old high achiever is one of the newest members of Sweden’s armed forces and a product of its fiercely competitive conscription process.

“It’s a privilege,” Forsberg says of being chosen for military service—less than 10% make the cut. In this exercise, she is playing an enemy intruder at an arms depot with her new regiment, which later this year will send forces to Latvia as part of Sweden’s first international mission as a North Atlantic Treaty Organization member.

To confront and deter an expansionist Moscow , the U.S. and many of Russia’s near neighbors are struggling to attract enough recruits to reinforce their militaries. Not so in Sweden, where each year the armed forces turn thousands of young men and women away.

As the newest member of NATO, Sweden is betting that the best way to bolster its defenses against Russian aggression is to stack its military with the country’s top performers. Conscription under the Swedish model now functions as a filter, not a dragnet.

All young men and women in Sweden must enlist, but rigorous testing sorts the best from the rest. That has created a virtuous recruitment circle where military service, lasting up to 15 months depending on the role, is regarded as prestigious and conscripts compete for spots. Afterward, they join the country’s reservists for 10 years, or until they turn 47.

The system has proved so successful at nurturing talent that former conscripts are headhunted by the civil service and prized by tech companies. It could provide a model for the U.S., which in 2022 had its toughest recruitment year in almost five decades, dragging on America’s military might. As a proportion of its population, Sweden’s annual armed-forces recruitment rate now tops that in the U.S.

For months, Forsberg trained for the conscription tests by lifting weights and braving the blistering cold to run along the seafront in her hometown of Kungsbacka.

“I’ve always wanted to be part of it,” Forsberg said of the army. “If someone says they’re in the military, you look up to them.”

Becoming battle ready

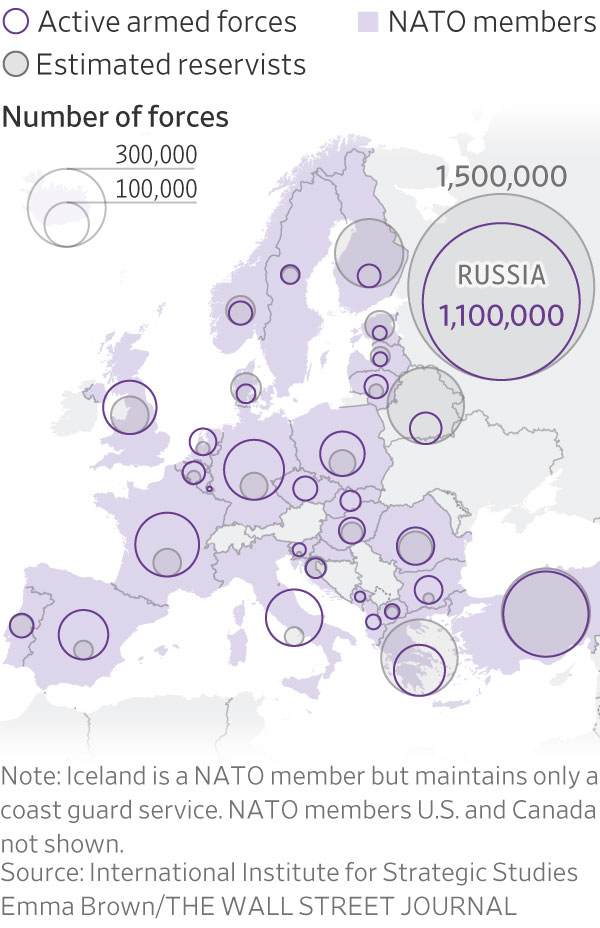

Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine has abruptly reawakened Europe to the necessity of maintaining sizable, battle-ready armies . European intelligence officials say Russia anticipates a conflict with NATO within the next decade, and aims to raise a standing army of 1.5 million by the end of 2026. Russia’s military superiority over Ukraine will continue to grow, “unless Western countries quickly step up,” one intelligence official said.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has dismissed warnings of a potential Russian attack on NATO members as “complete nonsense.” In early 2022, the Kremlin used similar language to ridicule American warnings that Russia planned to invade Ukraine.

German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has warned that Europe should prepare for possible war with Russia by the end of the decade. He also has called Germany’s abolition of conscription in 2011 a mistake, adding earlier this month that it should be reintroduced.

Comprehensive conscription was common throughout Europe in the 19th century when countries such as France and Germany manned their armed forces mostly with men from lower classes; Russia often employed a coercive version. During the American Civil War, both sides had drafts, but the U.S. only reintroduced it, along with Britain, during the two World Wars. After the Cold War, most countries abandoned the practice.

But Sweden, apart from a brief gap during the 2010s, has relied on conscription for more than a century to populate its army. This year, out of about 100,000 young Swedes who had to enlist, just 6,200 made the cut for conscription, an annual increase of slightly more than 10%. The country aims to reach 8,000 conscripts next year, and 10,000 soon after that.

Selection is based on physical and mental fitness, IQ tests and motivation to serve. Health issues such as allergies, asthma or eczema can rule recruits out.

Forsberg did so well on her tests that the army picked her to train for the highly-skilled role of artillery observer for a company of Combat Vehicle 90s in the South Scanian Regiment.

She began in March, an hour before the blue NATO flag with its white compass was hoisted on the base in Revingehed, marking the country’s accession to the alliance.

Not everyone who meets the military’s requirements wants to serve, and the armed forces have traditionally weeded out such people, to ensure that its soldiers are not just skilled, but also highly motivated. But to further increase its intake, the military might start insisting more of them join up, Swedish officials say. Evading the draft is punishable by a fine or up to a year in prison.

Long wars

While Western nations don’t have to match Russia soldier for soldier, the brutal war of attrition in Ukraine has shown that mass armies still matter, particularly in yearslong wars, said Jan Joel Andersson , senior analyst and expert on rearmament at the European Union Institute for Security Studies.

“NATO has far too few trained and equipped coherent units, or force packages, to fight a major war,” he said.

During a recent nine-day military exercise involving 1,000 soldiers and 200 officers, the South Scanian Regiment trained conscripts in Leopard battle tanks and Combat Vehicle 90s, both used by other European militaries, one of several ways Sweden is dovetailing with fellow NATO member states.

From a hill overlooking the training area’s rolling fields, a group of engineers from the Swedish defense contractor Saab guided a Martlet MI-2 drone above the canopy of a forest, shooting lasers at a CV90 below. The soldiers returned laser fire, hitting the drone, which high-tailed to the hill, lights blinking. Re-creating Ukrainian battlefield conditions, the scenario was meant to give conscripts a taste of modern warfare, where enemy attacks come by land and from the sky.

Shrunken forces

After the Cold War, European nations cut their forces to the bone and replaced large conscription armies with smaller professional forces. Aging populations and expensive social welfare states meant that manning even small armies became difficult.

At the same time, focus shifted from territorial defense to new threats such as terrorism, and support for international missions in Afghanistan and Iraq, which along with advances in weapons technology lessened the need for mass armies.

From 1990 to 2015, Germany—enlarged by reunification—shrank its combat battalion numbers from 215 to 34, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a London-based think tank. In the same period, other European nations followed suit. Italy’s battalion numbers fell by 67% and France’s dropped by almost as much. British battalions were cut by almost half.

The U.S. struggles, too. In 2022, the U.S. Army had its toughest recruiting year since the advent of the all self-enlisted military in 1973, missing its recruitment goal by 25%. After lowering its target from 65,000 to 55,000 recruits, the Army is optimistic about meeting the mark this year. The Navy, however, anticipates a shortfall of about 6,700 on its ambition to recruit 40,000 sailors, the second year in a row that it will undershoot.

Large-scale demilitarization

When the Berlin Wall fell, Sweden dismantled huge parts of its military infrastructure and reduced its troop strength by more than 90% from its peak in the 1960s. The Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces sounded the alarm in 2013, saying the country would only be able to defend itself against an armed aggressor for a week.

Today, Sweden can mobilize around 66,000 uniformed personnel, including some 12,000 reserves and over 20,000 home guards, compared with 850,000 men and women during the height of the Cold War in the 1960s. The aim is to increase the number of active forces to more than 100,000 by 2030.

“Sweden has gone from being a huge organization in the 1980s with a regiment in every town and city, to an anorexic organization in the mid 2000s,” said Johan Österberg , expert on military conscription with the Swedish Defence University. Rebuilding a military takes more than recruits, and even with sufficient numbers, “we don’t have buildings for them to sleep in,” he said.

Since 2017, about 100,000 Swedes each year must fill out an online questionnaire for the armed forces from which about 20% are selected to undergo psychological and physical testing. Around one-third of them are picked as conscripts.

In high school, “I dreamed about doing conscription,” said Ida Carlsson , who arrived at the South Scanian Regiment in March and was selected to become its first female reconnaissance platoon commander in 13 years. “I was very impatient.”

Norway has a similar conscription model to Sweden. Of about 60,000 young Norwegians, the armed forces each year select about 40% for tests and pick about 10,000 to serve. The Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany and Denmark also are looking at introducing or updating their conscription programs.

Because Swedish military service attracts the best in class of any generation, civilian employers value former conscripts. After 14 months of military service as a Persian interpreter, Anders Fridén completed a tour to Afghanistan and went straight into a job at the Swedish Embassy in Tehran. The foreign service explicitly advertised for applicants who had done military service, Fridén said.

Since then, he has worked as a management consultant in the U.S., and is now at a tech company in Zurich. The 35-year-old said all his employers had valued the skills his military service had taught him.

“I think there is a recognition in society that this is a useful thing to do,” he said.

Write to Sune Engel Rasmussen at sune.rasmussen@wsj.com