Danielle Gansky was 7 years old when an administrator at her upscale private girls’ school in suburban Philadelphia flagged problems with her academic performance. She was a bubbly and creative kid, but she was easily distracted in class and her schoolwork was sloppy.

The school told Gansky’s mother that the girl should see a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and prescribed a stimulant. Concerned that Danielle might get kicked out if her focus didn’t improve, her mother broke into tears and agreed. But the pills made Gansky agitated, moody and angry. So another doctor put her on Prozac.

More pills followed. Over the years, Gansky was always on two and sometimes three or more psychiatric drugs at once. By her late 20s, she had taken 14 different kinds of psychiatric pills.

None of it ever felt right. The pills dulled her mind and made her irritable or sleepy. But when Gansky complained about the drugs, her doctors would up her dose or try another medication.

“I was living in a body hijacked by the medication,” said Gansky, 29, who is still struggling to wean herself off an antidepressant. “I didn’t have the words or authority to challenge what I was being told.”

Tens of thousands of kids who take prescription ADHD medication also wind up on other powerful psychotropic drugs—including antipsychotics and antidepressants, studies show. For some of them, the ADHD drugs themselves can be a trigger, according to doctors, patients and psychologists, who say additional medications are often prescribed to manage side effects such as insomnia, despite limited scientific evidence supporting these combinations in young, developing brains.

About 7.1 million American children ages 3 to 17 have an ADHD diagnosis, according to an analysis of 2022 federal data. About half took ADHD medication for it that year, and prescriptions are growing.

The decision to treat ADHD with medication is often made by desperate parents trying to keep their kids from falling behind or being kicked out of school or daycare, parents and mental health clinicians say. For preschool-age kids, the drugs are often dispensed against pediatric guidelines, which call first for behavioral therapy, a treatment that can be hard to get. And mental health providers say the drugs are frequently prescribed to treat childhood trauma that has been misdiagnosed as ADHD.

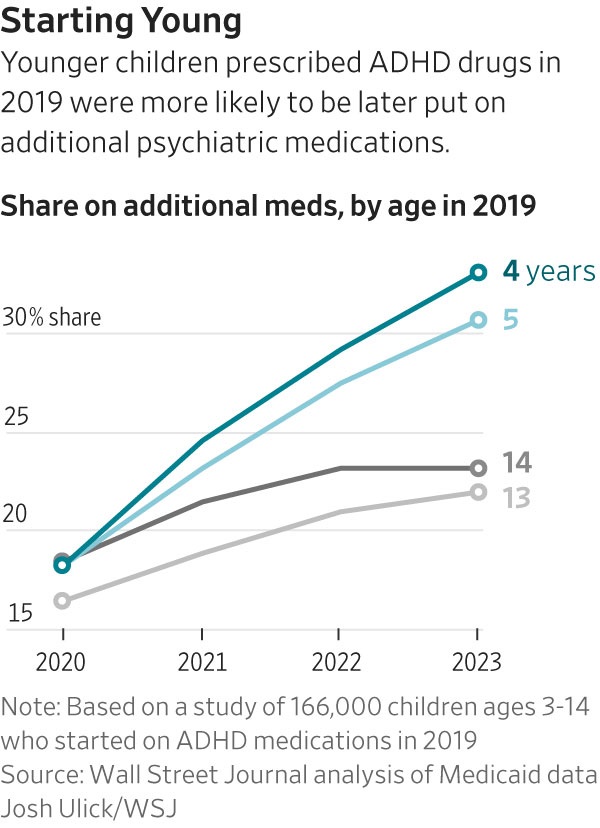

For one in five kids who take them, ADHD drugs are just the beginning. A Wall Street Journal analysis of Medicaid data from 2019 through 2023 shows that children who were prescribed a medication for ADHD were far more likely to take additional psychiatric drugs over the ensuing four years.

The Journal compared about 166,000 children aged 3 to 14 who started on ADHD medications in 2019 to kids who didn’t. The medicated group was more than five times as likely to be on additional psychiatric medications four years later. Factors such as differences in sex, race and foster-care status didn’t explain the gap.

The data also show that for most children, medications are the first stop in ADHD treatment. Only 37% of the kids newly prescribed ADHD drugs in 2019 had prior behavioral therapy appointments, the Journal’s analysis showed.

The Journal analysis identified nearly 5,000 providers who ordered ADHD drugs for at least 100 children each between 2019 and 2022. On average, they gave additional psychiatric drugs to 25% of their patients. A tiny number ordered the combinations at much higher rates, including 128 who did so for more than 60% of their patients.

Children taking ADHD medicines could be prescribed additional drugs for many reasons, and the Journal analysis didn’t assess what triggered the prescribing. ADHD and other conditions including depression and anxiety often occur together, researchers have found.

Clinical trials have shown ADHD drugs—among them stimulants such as Ritalin and Adderall—are safe and effective for many patients. But less is known about the impact of multiple psychiatric drugs on young children.

“We need long-term studies following young people to fully understand the effects of psychiatric medications on the developing brain,” said Dr. Mark Olfson, professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Antipsychotic medications are of particular concern, he said. Some studies suggest that adults taking antipsychotics for long periods experience cognitive decline, but long-term studies haven’t been conducted on children, he said.

“The best scientific evidence suggests that it is very rare for two or more medications in kids to be helpful and there are concerns about safety, because there can be additive adverse effects of different types of medications,” said Dr. Javeed Sukhera, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and chair of psychiatry at the Institute of Living at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut.

A child on several medications at once often hasn’t had a comprehensive evaluation by a child psychiatrist, Sukhera said. Stimulants can cause side effects that can be mistaken for an additional disorder. “When a young person shows up with anxiety after starting a stimulant, that doesn’t mean that they have an anxiety disorder,” he said.

Many adults say that ADHD medications vastly improved their lives, and some scientific studies show that medicating reduces risk of other potential problems such as juvenile delinquency and subsequent mental-health disorders.

Still, side effects of the ADHD medications on young children can be severe and unpredictable, sometimes pushing parents to accept additional pills to address them.

All too often, under pressure from preschools and elementary schools, many parents seek help from pediatricians or psychiatric nurse practitioners—who frequently lack in-depth training in pediatric mental health—rather than wait months or even years for appointments with behavioral specialists or child psychiatrists.

Alexandra Perez, a clinical psychologist at Emory University School of Medicine who works with young children on Medicaid and private insurance, said she has seen children as young as 4 on multiple psychiatric medications. Many have experienced adversity or trauma and have behavioral problems as a result that get labeled as ADHD, said Perez, who practices Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), a method that has been proven to reduce behavioral difficulties associated with ADHD.

“Children are quickly diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed medication,” she said. “That doesn’t tackle the root causes. We are putting the Band-Aid of medication on, a temporary fix.”

‘Like a zombie’

Easton was 3 years old when his daycare provider sent up a flare about his behavior. His inability to sit still was so disruptive that the provider said something had to change fast. His aunt and caregiver, Kymberly Stacks, was at wit’s end, and took Easton to Siskin Children’s Institute, a nonprofit healthcare organization in Tennessee that accepted his Medicaid insurance.

A physician assistant diagnosed him with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, and told Stacks that guanfacine, a blood-pressure medication often prescribed for ADHD, could calm him down enough to stay in daycare. She never disclosed that guanfacine wasn’t approved for toddlers by the Food and Drug Administration, said Stacks. (Doctors do prescribe it off-label to young children as an alternative to stimulants).

Siskin declined to comment.

“They were pretty on the edge with him,” Stacks said, of the daycare. “He had been written up multiple times. I think us putting him on meds helped him stay in daycare.”

On the medication, though, Easton “was like a zombie,” recalled Stacks, who has since adopted the boy, whose biological parents were unable to care for him. Each time the family raised concerns to the physician assistant, she upped his dose.

As the dosage lost effectiveness every few months, he again became aggressive to other children in daycare. He often had to sit in the school director’s office all day. One of Easton’s friends was expelled for exhibiting similar behaviors, leading Stacks to search for additional help.

A new psychiatrist told Stacks he was overmedicated on guanfacine and put him on Abilify, an antipsychotic, which seemed to lessen his defiance. Adding the stimulant Evekeo only made him more hyperactive; Concerta and ProCentra also didn’t help.

Easton has rotated on and off of six psychiatric medications, many times on two at the same time, since the age of three.

Frustrated, Stacks weaned Easton off all the meds over the summer with his doctor’s blessing. His ADHD tendencies didn’t seem to change much; he seemed like a normal 6-year-old kid who loved to run and play outside. But his outlook darkened: He threatened to stab a child at camp and would laugh when he got into trouble.

Doctors put him back on the antipsychotic and he seemed to stabilize but started gaining weight. Once kindergarten started, the phone calls home began again: he wouldn’t stay seated. The school suggested he try stimulants again.

In recent weeks, Stacks tried Ritalin (it made him bounce off the walls and act “completely unmedicated”) and now, Quelbree, another ADHD medication.

“I constantly think he was put on medication way too young, but no doctor ever said anything,” said Stacks, who works with autistic children as a behavioral therapist.

The Journal’s Medicaid analysis additionally found that patients who started ADHD medications early were more likely to be prescribed additional psychiatric drugs. The youngest children—those between 4 and 6 years old in 2019—were the most likely to be on additional psychiatric medications four years later. The analysis didn’t assess the reasons.

Over 23% of the ADHD group in the Journal’s analysis—more than 39,000 children—were on at least two psychiatric medications at once by 2023. More than 4,400 were on four different drugs simultaneously, with a vast majority of them on an antipsychotic.

In a 2017 study looking at Medicaid children diagnosed with ADHD between 1999 and 2006, researchers found that for 60% of the years in which children were on multidrug regimens, they had additional mental health diagnoses like anxiety and depression that could explain the prescribing. But for nearly 40% of those years, they only had an ADHD diagnosis. Some clinicians may be reluctant to assign diagnoses to young children, according to the study.

‘Mental-health desert’

Many parents say that effective behavioral therapy can be hard, if not impossible, to find.

Hayley Rogers’ son was diagnosed with ADHD in kindergarten at age five. As he fell behind in first grade, his doctor referred him to occupational therapy and a psychologist.

Rogers said she took a day off work and called every single psychologist or therapist she could find, both in-network with her insurance and out-of-network, and “literally nobody was accepting new patients for in-person care in the entire Seattle area. We got zero support because there is such a shortage with behavioral health for pediatrics.”

With no options for therapy, she started her son on the Adderall dose he was prescribed, she said. The medication has generally helped her 8-year-old’s impulse control, but he still struggles with emotional ups and downs at times.

More than 42% of children aged 3 to 5 are prescribed medication within 30 days of an ADHD diagnosis, meaning doctors may be directing parents to drugs before giving behavioral therapy a chance to work, according to a 2025 Stanford University paper. That’s despite American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines advising against starting with medication for those ages, instead recommending behavioral interventions first.

The Journal’s analysis showed that about one-third of 4-year-olds who were prescribed ADHD drugs in 2019 were taking additional psych medications four years later.

Rogers says she gave up waiting, with no end in sight, for a therapy appointment for her son. She now asks ChatGPT what to say when she needs direction in tough moments, and it provides scripts to her based on ADHD parenting advice.

In Louisiana—one of the top states for prescribing ADHD meds to children, according to federal data—child psychologist Amy Mikolajewski, a PCIT practitioner and assistant professor at Louisiana State University, says “we are a mental-health desert.”

Mikolajewski has observed how behavioral therapy and small changes–like breaking up tasks and positive reinforcement when kids are doing the right thing—can significantly help. In PCIT, Mikolajewski helps parents through a monthslong training program that is designed to help strengthen their bonds with their children and address disruptive behaviors, aggression, defiance and other ADHD symptoms. Some parents who have gone through it say they have seen dramatic improvements in their preschoolers’ symptoms.

Untreated Trauma

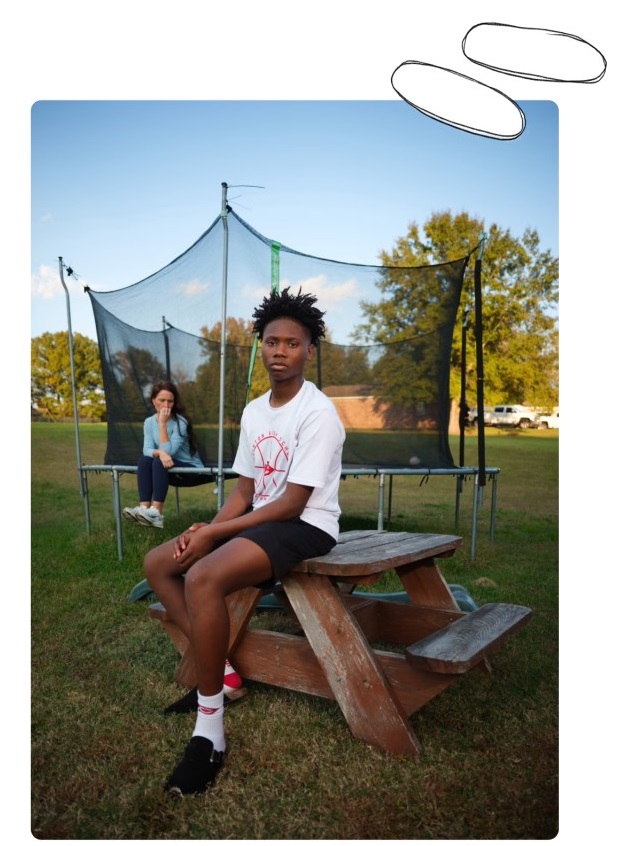

When he was 11, Tyrell Cooley was taking a very high dose of Concerta, along with guanfacine, sometimes used as an adjunct to a stimulant, at night. He had been impulsive, couldn’t sit still and hated school—his stomach hurt every morning when he went. “I used to get in trouble a lot in school,” Tyrell recalled. “I had a detention every other day.”

He was frequently anxious and sullen, a result of trauma from his birth mother’s drug use, according to his adoptive mother, Mallory Cooley. He was medicated not to treat the underlying psychiatric condition, his mother said, but to keep him calm in school. “People just wanted to give him medications to sit still and not actually deal with why he’s doing what he’s doing,” she said.

Tyrell hated medication. He had little energy or appetite. “It made me feel drained overall,” he said. “I didn’t like talking to people. I couldn’t bring up the energy in my body to talk.”

The Cooleys spent a month searching for a family therapy program for Tyrell, who is on Medicaid. They wanted one that would address the trauma of an unstable childhood they felt was driving his angry, impulsive behavior. Twice a week for about a year a therapist came to their home in Clinton, Miss., and Tyrell’s school. They worked with Tyrell on how to control his anger and impulsiveness and how to talk with people and trust them. The therapist met with the family to talk about how to help Tyrell.

The Cooleys gradually weaned Tyrell off his medications, feeling that the pills were fueling some of the wild behavior and masking problems that were better dealt with in talk therapy.

Tyrell, now 15, said he feels much better off the medication and after the therapy. “I’m more connected with people,” he said. His mother said he “talks 24/7 all day every day” and while he can be hyperactive, “I do feel he can control himself.”

Jennifer Havens, the chair of the department of child and adolescent psychiatry at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, says her field has done children a disservice by failing to recognize trauma—and rather treat manifestations of trauma as ADHD or other psychiatric disorders like bipolar disorder or psychosis.

“We have made a mess and it’s dangerous because some kids really need medication, and if we just said ‘no meds,’ that’s not the answer, but if a kid is on five, six, seven medications, that’s just wrong.”

‘The real guinea pig’

Jordan McDonough, a home inspector with three children who was himself medicated from childhood, is wrestling with how to help his 4-year-old son showing signs of ADHD.

McDonough took Ritalin from age 5. Doctors kept “upping it and upping it,” he recalls. By third grade, he was on Wellbutrin for depression, as his parents went through problems at home. He cycled through antidepressants Celexa and Lexapro, ADHD medications Concerta and Strattera, as well as other prescriptions he can’t remember over the ensuing years.

At 14, McDonough attempted suicide. In the hospital, he recalls having an epiphany. “If I’m going to be sick forever, why don’t I just use my own devices instead of taking this pressed poison?” He had a lucid conversation with the ER doctor that night, who agreed to take him off the medications.

Life off pills has been uneven. McDonough struggled with marijuana use and still feels he hasn’t always “carried his weight” at home. His teenage son is on Adderall and Zoloft after a turbulent childhood with an addicted mother. McDonough hopes to avoid prescriptions for as long as possible for his younger son, who is starting to do well and make friends at a special-education, small preschool.

Nancy Gansky lives with regret over her decision to give her daughter medication. When Danielle was 11, doctors added Wellbutrin and guanfacine to her medications briefly. Then Ativan or Xanax in her teens. An antipsychotic, risperidone, when she was 15 made her sick and put her in the hospital.

When Danielle was 16 years old and on Prozac, Concerta, and Ativan, she felt dizzy and so tired she couldn’t get up in the morning. She was late so often for school that administrators said she might have to repeat some classes and asked for a doctor’s note to explain the tardiness. The doctor wrote the note—and raised her Prozac dose. More antipsychotics came in her 20s.

“The doctors would tell us, oh, that’s just her. She needs more medicine,” Gansky’s mother said. “I took it at face value.”

Gansky quit taking a stimulant regularly in high school, but remains on an antidepressant, fluvoxamine. She has tried to stop it twice, but fell into painful withdrawals—leading to more medications, including antipsychotics Seroquel and Zyprexa, which prompted symptoms of their own, like shaking and emotional numbness. She has had to go to the emergency room a few times, her body shaking. Her brain fog and some other symptoms remain.

She lives with her parents and had to pull out of a master’s program in school counseling. Her experience with withdrawal from her antidepressant led her to push for change as an adviser to a new advocacy group and to attend events held by the Make America Healthy Again movement, led by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The decades of medication, Gansky said, “changed my brain.” “I feel like I am the real long-term study that the pharmaceutical companies have neglected to do,” she said. “I’m the real guinea pig.”

Illustrations by Audrey Valbuena/WSJ; Adobe Stock (2)

Write to Shalini Ramachandran at Shalini.Ramachandran@wsj.com , Betsy McKay at betsy.mckay@wsj.com and Tom McGinty at Tom.McGinty@wsj.com