LONDON—For the first time, populist or far-right parties are leading the polls in the U.K., France and Germany, the latest sign of growing voter discontent in much of the continent following years of high immigration and inflation.

Far-right and anti-immigration parties have already entered government in countries such as Italy, Finland and the Netherlands. But this year marks the first time that they have been ahead in Europe’s biggest economies at the same time. That could provoke a period of political turbulence in all three countries, even if national elections are likely still a few years away.

“It’s significant. Leaders in all three countries are grappling with an ascendant far right that looks on the cusp of power unless politicians can address what’s fueling the rise, which is immigration and cost of living,” said Mujtaba Rahman , head of Europe for risk consulting firm Eurasia.

France’s anti-immigration National Rally has had a consistent lead in polls this year. An Elabe poll last month showed Jordan Bardella, the young protégé of the far-right leader Marine Le Pen , was the most popular with an approval rating of 36%. Polling for the next presidential vote also suggests National Rally’s candidate—whether it is Bardella or Le Pen—would lead the first round.

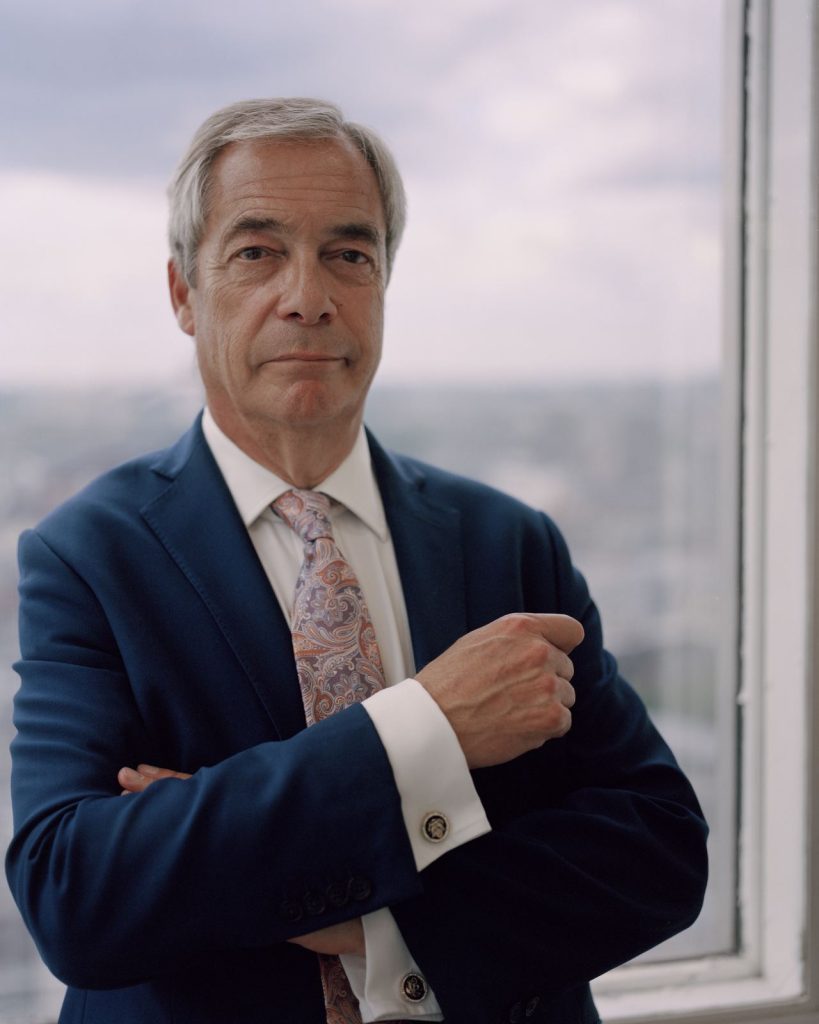

In the U.K., the anti-immigration Reform UK, led by the former Brexiteer Nigel Farage , has surged in the past six months and is now comfortably ahead in opinion polls of the ruling Labour Party and the opposition Conservatives, the political duopoly that has dominated British politics for the past century.

Nigel Farage leads the anti-immigration Reform UK. Photo: Dominic Whisson for WSJ

In Germany, the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, has been neck-and-neck with the ruling center-right Christian Democratic Union in polls since the start of the year. The AfD has pulled slightly ahead in recent weeks, the first time it has done so since April, according to Forsa, one of the country’s leading pollsters.

Friedrich Merz, leader of Germany’s governing Christian Democratic Union. Photo: Marzena Skubatz for WSJ

Like the U.S., much of Europe has experienced two things at the same time since the pandemic: record levels of immigration that have caused a voter backlash, and a surge in inflation that has now eased but left prices for many goods much higher than before—leaving many voters feeling worse off. Social media has also polarized opinions.

Unlike the U.S., however, much of Europe has almost no economic growth, fueling a widespread sense that the continent faces years of drift , as well as political gridlock.

The sense of economic decline together with rapid immigration is a toxic combination that has turned many voters against established political parties, said Jérémie Gallon, a former French diplomat and head of Europe for consulting firm McLarty Associates. “It’s the same story from smaller English cities to the French countryside to German towns, where many people feel like the traditional elites look down on them or ignore their concerns,” he said.

A vacant building in Grantham, England. Photo: Dominic Whisson for WSJ

Bardella and National Rally have tapped into widespread anxiety that France’s Muslim minority, one of the largest in Europe, is encroaching on the secular values of the French Republic, and into a perceived decline of living standards among working-class and middle-class families. In recent years, National Rally has evolved from a fringe protest movement to the country’s largest single party in the National Assembly, France’s lower house of Parliament.

That hasn’t proved enough yet for the far-right party to take the reins of government, but it has made the country increasingly difficult to govern. France’s government is again on the brink of collapse , less than nine months after conservative French Prime Minister Michel Barnier was ousted from office.

This past week, National Rally pledged to vote against the government again on Sept. 8, when centrist Prime Minister François Bayrou plans to hold a confidence vote in the National Assembly ahead of what are expected to be difficult negotiations for a new budget. On Tuesday, Bardella called on President Emmanuel Macron to hold new parliamentary elections or resign.

In recent years, Germany and the U.K. both saw the biggest surges in immigration in their history, even if the numbers have begun to fall this year. In Germany, the share of residents born outside the country surged from just over 15% in 2017 to a record high of 22% in 2024, according to government data. That compares with about 16% in the U.S.

The U.K., meanwhile, has grappled with a record rise in legal and illegal immigration. Some 4.5 million people arrived legally between 2021 and 2024, primarily from India, Nigeria and China. That is slightly more than those who legally entered the U.S.—which has about five times the population of the U.K.—over that time. In addition, tens of thousands of people have illegally crossed the English Channel on flimsy boats each year to claim asylum.

So far this year, record numbers of people—29,000 through the end of August—have made the crossing, sparking growing pressure on Prime Minister Keir Starmer , who came to power last year vowing to “smash the gangs” that control migrant smuggling and reduce the crossings.

Adding to the pressure on Starmer, protests flared this summer in some English towns over the use of local hotels where the government is paying for migrants to stay until their asylum cases are resolved.

In Germany, a surprising feature of the AfD’s latest surge is that it has coincided with a drop in immigration numbers under the current government. In the midst of tougher border controls, new asylum requests fell more than a third in the first half of the year compared with the same period last year. Friedrich Merz , the conservative chancellor, has also done away with some of his predecessor’s green policies, often criticized as excessive by the AfD.

A raft of growth-supporting measures, from corporate tax cuts to rising infrastructure investments, have yet to show any effect, however. The economy contracted by 0.3% in the most recent quarter, extending a two-year recession.

This, said Manfred Güllner, head of Forsa, was one of the factors for the AfD’s recent surge. “Voters are seeing a lot of action, but they’re not feeling any effect,” he said, pointing to the mismatch—or at least the time lag—between promises and results.

The AfD has campaigned for the deportations of immigrants in the country illegally; for Germany to leave the European Union and the euro currency; and for the country to rethink its culture of Holocaust remembrance. It rejects the notion of man-made climate change. Its economic polices are similar to those of Merz’s Christian Democratic Union, but it also wants to increase pension benefits and limit noncitizens’ access to welfare benefits.

Some of its leaders and lawmakers have drawn scrutiny for their sympathies toward Russia and China —the party has called for Germany to resume energy deals with Moscow—while economists have said its push to leave the EU could damage the country’s export industries. But the party has also enjoyed the support of people close to President Trump, in particular Vice President JD Vance and tech billionaire Elon Musk .

The AfD has tapped into economic frustration to buttress its appeal. Its program in the lead-up to February’s federal election focused on economic proposals, ahead of topics such as security and immigration. This has helped it gather support among blue-collar voters in economically depressed regions far away from the party’s historical strongholds in former East Germany, such as the Ruhr, the industrial Rust Belt region east of the Rhine Valley.

Write to David Luhnow at david.luhnow@wsj.com , Bertrand Benoit at bertrand.benoit@wsj.com and Noemie Bisserbe at noemie.bisserbe@wsj.com