LANDENBERG, Pa.—When Milan Jevtitch finished his Ph.D in chemical engineering in 1986, he got a job right away at Procter & Gamble. He climbed the corporate ladder, bought a spacious four-bedroom home for his family and saved for a comfortable retirement.

His daughter’s job search has been much tougher. Anais Jevtitch , 24, graduated cum laude from Ohio University in December 2023 and has lost count of the number of applications she’s submitted for positions in marketing, social media and film and television production. Nearly two years later she is still living in her parents’ colonial-style home on the outskirts of Philadelphia, working part-time jobs as she continues her relentless search.

“‘Ghosted’ is the term she uses,” Jevtitch, 68, said of his daughter. “I’m very frustrated, almost angry…It’s really difficult for her to even get interviews.”

Ask many older Americans how they are faring financially and they’ll tell you they are comfortable. Their houses and 401(k)s have soared in value and they’re looking forward to secure retirements. Yet many are brimming with pessimism about the economy because they see how their children are struggling—to find jobs, to afford mortgages or even rent, to pay for healthcare and child care.

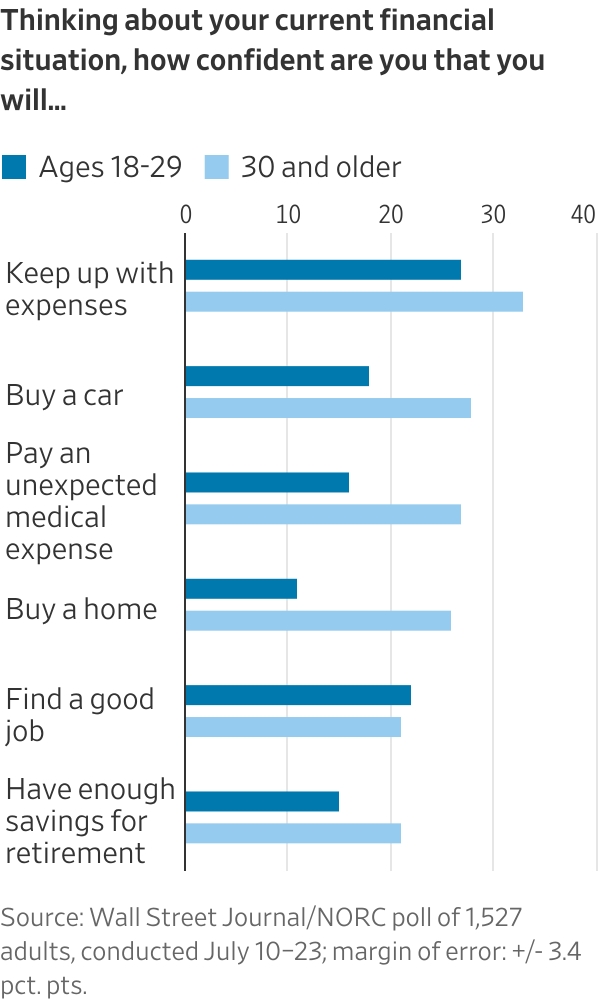

In a July Wall Street Journal-NORC poll that examined Americans’ economic views, the most common respondent was someone comfortable with his or her own finances but gloomy about the economy’s future. Nearly 70% said they believe the American dream no longer holds true or never did, the highest level in nearly 15 years of surveys. Nearly 80% weren’t confident that life for their children would be better.

The divided fortunes of parents and their adult children are part of a split-screen economy that is delivering robust returns for high earners and many older Americans while conditions for many others worsen. There have always been divisions between high-earning Americans and others, such as younger or low-income workers. But those divisions are now widening within the same families, flipping traditional expectations about younger generations economically surpassing their elders.

In some cases, financially secure parents are subsidizing their children’s rents, helping them travel for job interviews and paying for job coaches. Other families are turning to multigenerational living arrangements.

Recent college graduates are taking a particular hit. They typically face higher unemployment than older workers, but the gap is widening . While the overall unemployment rate rose to 4.3% in August, it is much higher for recent college graduates—6.5% over the 12 months ending in August. That is about the highest level in a decade , excluding the pandemic unemployment spike.

Some economists blame AI for replacing entry-level roles. Others say companies have slowed hiring because they are uncertain how tariffs and other regulatory changes will affect their costs. Recent grads report submitting hundreds of applications through LinkedIn and other portals and barely ever getting a response.

“They are getting absolute radio silence and becoming increasingly desperate to stand out,” Ben Tobin , a career coach in Portland, Ore., said of the computer-science graduates he helps. “Almost all the ones I talk to are either being supported by their parents or living with them. Many are finding some kind of other job to fill the gap…One is walking dogs through an app.”

A 50% leap in home prices since the beginning of the pandemic is another sore spot. Young Americans have typically had to save to buy a home, but many of today’s young adults have given up the idea of ever affording one.

In the WSJ-NORC poll, about 23% of respondents said they were extremely or very confident that they could afford to buy a home, but only 11% felt the same about today’s children’s generation. About 32% were confident they could keep up with their expenses but less than half that share were confident of the next generation’s ability to do so.

On a recent afternoon, Anais Jevtitch had just returned home from a busy day of job searching. In the morning she attended a local networking event, where she collected business cards from marketing professionals and asked for job leads. She also participated in the group activity: writing an obituary for herself, as a way to focus on her life goals.

“I was the youngest person in the room, so writing an obituary for myself at 24 years old was kind of a crazy first activity,” she said from her parents’ living room while the family dogs ran through fall leaves in the yard. After the networking event, she visited her career coach in nearby Kennett Square. Ed Samuel—whom her father had recently hired to help her—worked with Anais to refine her LinkedIn profile.

Later, from a childhood bedroom decorated with Star Wars and rock-band posters, Anais opened her laptop and pointed to the 50 versions of her résumé she has written since February. Then she clicked over to LinkedIn to check her connections count: 270. Samuel has been pushing her to reach 500 to raise her visibility with recruiters.

Anais’s mother, Bettina Jevtitch , remembers an easier path to the good life when she was young. Bettina and her husband were both French immigrants to the U.S. when they met in Cincinnati in the 1990s. One of her friends back then managed to buy a modest home and car from her bartending income. “There is no way that now we can do that,” she said. “There is no way that Anais can even afford to move out of here.”

Steven Conn , a history professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, was struck recently by his students’ reactions to the film “A Raisin in the Sun,” which concludes with a Black family fulfilling its long-delayed dream of buying a home in 1950s Chicago. “One of my students said, ‘Yes, that is their American dream. We don’t get that.’ And everyone in class nodded their heads. Owning their own home is already something they don’t believe will happen,” Conn said.

Conn’s son, Zach, has been searching for a job since graduating this summer from Macalester College in Minnesota. For now, Zach is living rent-free in a Philadelphia apartment owned by his parents, where he estimates he has applied for about 400 jobs since July, in fields from shipping to museum work.

“You’re shouting into this void that just feels pretty dehumanizing,” Zach said. Many of his friends are also relying on family for financial support, he added. “There is this sense of, we’ll never be able to buy a house and we’ll never be able to build the life that we were dreaming of.”

Steven Conn and his wife also own a second home in Ohio and have solid retirement savings. They faced their own challenges finding jobs in the difficult academic market when they were starting out, Conn said. But Zach’s struggles have helped darken Conn’s views on the economy.

“There is something different in the world of employers and employment. And I think it has a lot to do with the digitization of this process…It feels lonelier, it feels more isolating than I remember it when I was his age,” Conn said.

North of Chicago, in the prosperous suburb of Wilmette, Ill., Sam Cummins was preparing this week for a rare opportunity in the hyper-digital application process: a virtual one-way interview. “You talk to the computer yourself,” Cummins, who graduated from DePauw University in May, explained from his parents’ Cape Cod-style home.

Cummins is applying for sometimes dozens of jobs a day in insurance, banking and other fields, and even brings his laptop to his caddying gig at a local country club to pursue leads between rounds. He always appreciates when golfers offer to put in a word for him, though he worries such referrals don’t always break through the labyrinth of automation.

His mother, Susan Troy , called the process “soul destroying.”

“You always hear that with a liberal arts degree from a good school you can do many things, you are very hirable,” she said, adding that she was still hopeful he would find a job soon. “But here we are in mid-October.”

Sam Cummins, with his mother, Susan Troy. Sometimes he applies for dozens of jobs in a single day. Jeanne Whalen/WSJ

Mary Lovely , senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C., agrees that past generations faced their own troubles. The 1970s oil shock and stagflation clubbed the economy when she was a teen, and high interest rates thwarted home buyers in the 1980s. But when she went to college, she wasn’t worried about finding a job, and when she found one it came with health insurance. “I just don’t think these things took up such high multiples of our income,” she said.

Lovely has seen the obstacles facing today’s young people in her professional research and in her own family. Her two adult children have relied on their parents for financial support in recent years while facing a tough job market and soaring costs for healthcare and housing.

“Fortunately we can afford to help them,” Lovely said. But she worries about wider opportunities for the young generation.

“We’re not giving them what they need to really get off to a good start,” she said. “I have lots of friends who are going through the same thing and are helping their kids if they can. And a lot of people are talking about it because they realize it’s not their fault. It’s not that their kid’s an idiot…it’s just so much bigger than the individual kids.”

Write to Jeanne Whalen at Jeanne.Whalen@wsj.com