Teenagers in English classrooms today in many ways seem a world apart from students decades ago. The books sitting on their desks, however, are remarkably similar.

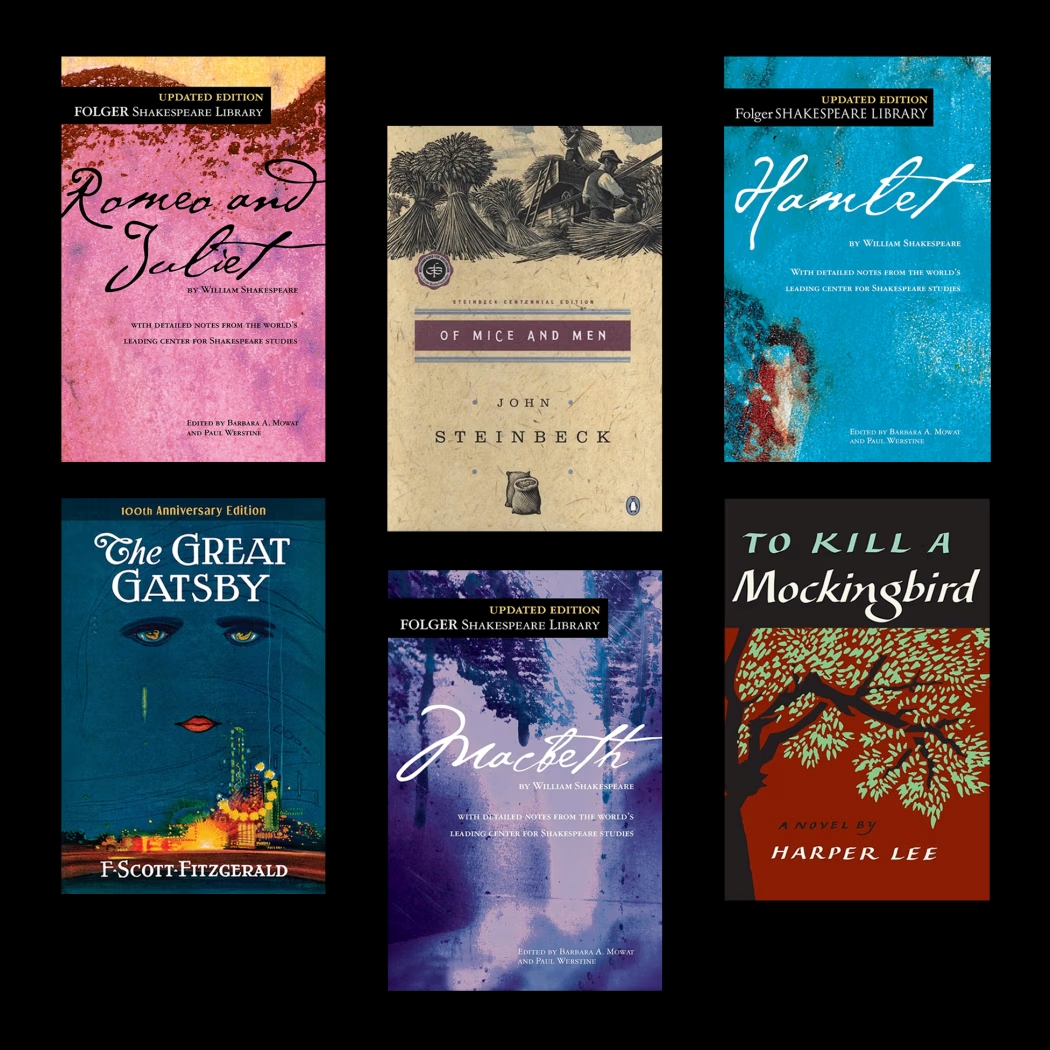

Classics including Shakespeare plays, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” and Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” all appear in the top 10 books assigned by English teachers at public middle and high schools today, according to a new report. Six of the top 10—John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” and “Hamlet” among them—overlap with the most-taught books reported in an influential 1989 study.

“We’re all shocked that what’s being taught has shifted so little from 30 years prior,” said Emily Kirkpatrick, the executive director of the National Council of Teachers of English, which produced the new report.

The staying power of the classics, Kirkpatrick and English teachers say, has as much to do with inertia as literary merit. Building the curriculum around a book and buying physical copies for each student takes time and resources. The internet is awash with ways to teach “Romeo and Juliet,” the most popular book on the new list, but teachers say fewer resources exist related to newer releases.

Introducing a new text also often involves several layers of approvals and scrutiny.

When high-school English teacher Gina Kortuem noticed her sophomores were no longer responding to “Animal Farm,” by George Orwell, she wanted to sub in Trevor Noah’s 2016 autobiography “Born a Crime.”

She learned the timing wasn’t right at her parochial school in suburban St. Paul, Minn., to buy a new batch of books. Kortuem herself also started to question the age-appropriateness of some of the language in the comedian’s memoir, which tracks his upbringing as a mixed-race child in apartheid South Africa. Instead, Kortuem decided to teach “Julius Caesar.”

“If it’s newer, fewer people have heard of it, and you have to push so much harder to get it approved,” she said.

As the student population in America’s public schools becomes more diverse—white students are no longer the majority, at 44%—the English teachers association and others have encouraged teaching texts from a wider range of voices. All of the authors of the top 10 books are white, with eight by men and two by women.

Long Island, N.Y., high-school teacher Brian Sztabnik has taught a lot of the classics in his Advanced Placement classes, including Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” and Miller’s “Death of a Salesman.” A few years ago, he added a newer historical fiction book, “Mudbound” by Hillary Jordan, after hearing about it in online teacher forums.

One year, Jordan came to visit Sztabnik’s classroom, giving the students a chance to ask her questions about the novel, set in 1946 Mississippi. “Just that possibility of real-life authors being able to interact with students,” Sztabnik said, “could be that one small thing that bridges that gap from absolute boredom and apathy to engagement.”

Some teachers accomplish greater diversity through short stories, poems and excerpts, which are easier to add and subtract from lessons than full-length books.

The power of the classics is their ability to create shared cultural touchpoints, said Michael Hicks, a recently retired English teacher in Los Angeles. “We need these through lines,” he said. “We need common ways to think about our culture and talk about things.”

The new study is drawn from in-depth surveys of more than 4,000 middle- and high-school English teachers. Almost 44% of the respondents said they had experienced some form of censorship regarding which books they could teach, from parents, school boards or elsewhere.

Some of the most censored titles teachers reported were Toni Morrison’s 1970 novel “The Bluest Eye,” “The Hate U Give,” a 2017 young-adult novel by Angie Thomas, and 2007’s “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie.

Some classics were as popular to teach as to ban, like Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”—a top book in the 1980s—and Harper Lee’s “To Kill A Mockingbird,” which was also among the current most-taught books.

The report found that teachers in more affluent and whiter areas had more autonomy in choosing their own curriculum and books. About one in five teachers said they had the freedom to choose all of their texts, with one in five also saying none of the texts were their choice.

The National Council of Teachers of English says the report is the most comprehensive look at what’s being taught by English teachers since a 1989 federally funded survey done by State University of New York researchers.

In the smartphone and TikTok era, English teachers have battled growing disengagement from teenagers, who sometimes have trouble focusing on full books. In a federal survey of students who were 13 as of 2023, 14% reported reading for fun almost every day, down from 27% in 2012 and 35% in 1984.

Sticking with only the classics, said Rex Ovalle, a teacher at Oak Park and River Forest High School in Illinois, isn’t the way to win over modern teens.

“I more than anything want to create a lifelong reader,” he said.

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com