When slavery ended on Dec. 6, 1865, millions of African-Americans were emancipated with little more than the tattered work clothes on their backs. The 13th Amendment resolved the founding contradiction of a Republic built on liberty yet fueled by enslaved labor. But freedom came without land, capital or institutional support—casting Black Americans into the world without the tools or resources needed to survive, let alone thrive.

Poverty, homelessness and exclusion from banking, job training, education or business formation were the realities facing most African-Americans after emancipation. Some Black communities managed to flourish in Northern states such as New York, California, Pennsylvania and Ohio. But most lived in the South, where schools, banks, housing and essential services for Black Americans were nearly nonexistent.

The task was enormous: Someone had to build these foundations from scratch.

The first attempt came with the Freedmen’s Bureau, a government effort established by Congress in the final days of the Civil War, with the support of President Lincoln, to aid Black freedpeople and poor white refugees. The bureau did valiant work—building schools for Black children, supporting land-grant universities, providing housing aid and expanding access to capital. But these efforts were short-lived. The Freedmen’s Bureau was abolished in 1872, just seven years after its founding, its work barely having made a dent.

Into this void stepped a generation of Black entrepreneurs—largely unknown today—who built the banks, businesses and institutions that made freedom real. They were the architects of Black America.

Robert Reed Church was among them. Once a slave, he became one of the South’s most powerful figures and one of America’s first Black millionaires. He transformed Memphis’s Beale Street into a hub of Black enterprise and culture.

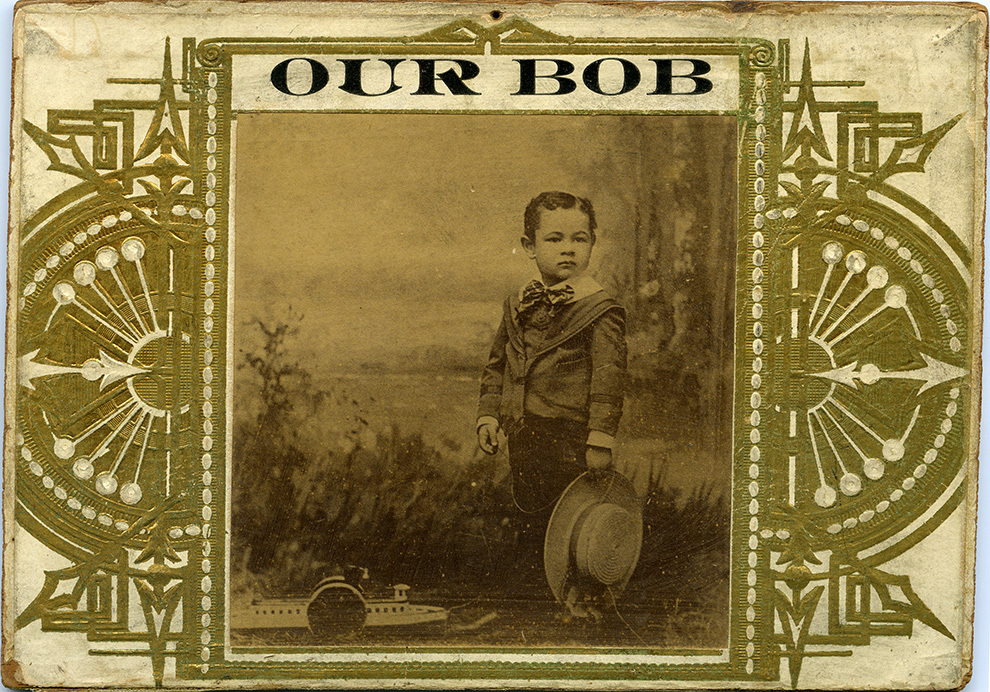

Studio portrait of Robert Reed Church as a young man. CHURCH FAMILY PAPERS/UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS LIBRARIES

But Church was more than a self-made man; he was a force, challenging the racial and economic order at every turn. He fought for Black voting rights and education, lobbied presidents, governors, senators and civil-rights leaders—and when necessary, picked up a gun to defend his people against lynch mobs.

A defining moment

On a warm spring day in 1862, the Confederate Navy boarded the Victoria, a lavish steam-powered gambling riverboat owned by Memphis businessman Capt. Charles Beckwith Church. The gray-uniformed soldiers informed the crew and the captain that the ship had been commandeered for the war. Naval officers carried out the velvet chaises and card tables that lined its cabin and refitted the vessel for battle. Among the captured “cargo” was an enslaved man named Robert Reed Church.

Church was tall, with sand-colored skin, slicked-back black hair, piercing eyes and a thin mustache. He was stoic and spartan, but his calm countenance concealed a fiery spirit. Raised from the age of 12 on a bawdy riverboat, Church—the unacknowledged son of Capt. Church and an enslaved woman named Emmaline—learned to always strike back anyone who struck him.

He kept to himself during the war, following the orders the Confederate soldiers gave him. But the morning after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Memphis, Church decided to make a break for it. Amid the chaos and gun smoke, he made his way to the edge of the ship’s deck. He plunged into the river, battling swift currents to reach the Memphis bluffs, soaked and shivering as if he had been baptized.

That moment reshaped his life and set a course to alter Black America’s economic destiny.

A business built on defiance

Like most formerly enslaved people, Church was denied formal schooling as a child. Instead, he learned from his life experiences as an enslaved steward on the Victoria. Working on the floor of the ship’s smoke-filled gaming parlor served as a hands-on education in the gambling and entertainment business.

In 1866, backed by his wife, Lou Church, a successful African-American hairdresser, Church made plans to open a billiard hall with an attached nightclub in Memphis. He secured a storefront and applied for an operating license with the city, but was denied because of his race. Church opened his doors anyway. A few days later, police arrived to arrest him and dragged him from his establishment in front of an onlooking crowd.

Church fought back against the charges that he was operating without a license, claiming that he had been denied the paperwork on the basis of race. To the shock of many in Memphis, Church won his case—a victory that declared Black Americans wouldn’t be so easily denied their rights in this new era.

The billiard hall owned and operated by Church. Photo: Church Family Papers/University of Memphis Libraries

Church became a household name in Memphis, and his club became a sensation, with lines stretching around the block. Inside, ragtime pianos mingled with the clack of billiard balls. Young people danced beneath flickering gaslights. Tennessee high-rollers came for high-stakes card games. At his establishment, Church mingled with a powerful mix—from ex-Confederate Army general Nathan Bedford Forrest to Hiram Revels, the first Black American to serve in the U.S. Senate—the symbols of a fragile new social order.

In May 1866, racial violence exploded in Memphis. Former Confederates, many now police officers, resented Black enfranchisement and federal oversight. This bubbled over into a clash between Memphis police and Black federal troops that ignited a race riot that left dozens dead, many wounded and Black schools burned. Church, Memphis’s wealthiest Black man at the time, was targeted. His wife begged him to stay home, but he went to work and stood defiantly behind his bar. Gunmen eventually arrived and shot through his pane-glass shop window; Church was hit.

Bleeding from the head, Church was left for dead. But he survived, albeit with a bullet lodged deep in his skull. He wore a revolver on his hip thereafter and numbed chronic headaches with whiskey and morphine. His wounds fueled a resolve to build his business and Black economic power.

The rise of a real-estate magnate

When yellow-fever epidemics devastated Memphis in 1873 and 1878, killing a undefined fifth of its population, Church saw opportunity. He bought abandoned properties for pennies and purchased municipal bonds, pumping capital into a city that once tried to kill him.

By 1885, Church controlled prime real estate on Beale Street, transforming it into Black Memphis’s cultural and economic heartbeat. He leased homes to Black workers and rented storefronts to businesses, bars and clubs.

Church reinvested his wealth in Memphis, beginning with a discreet money-lending operation in the 1870s. From behind the bar at his billiard hall, he lent out wads of cash. Eventually, he formalized his business by opening the Solvent Savings Bank & Trust in 1906. His bank was part of a wave of 134 Black-owned banks across the country that provided essential services to African-Americans barred from opening accounts at white-owned banks. Without access to the capital these banks provided, Black businesses, grocery stores, home lenders and agricultural enterprises couldn’t have supplied the food, housing and services that formed the backbone of Black life.

During Reconstruction, Church began building political influence by advising Sen. Revels and P.B.S. Pinchback, the Black governor of Louisiana. Their efforts advanced Black political power, but all lost their seats when Reconstruction ended. Undeterred, Church continued working to build political influence and advocate for African-Americans.

At the turn of the century, Church leveraged his influence to expand the political power of Black voters. After making significant contributions to the Republican Party, he helped arrange a dinner between President Theodore Roosevelt and educator and author Booker T. Washington at the White House—the first time an African-American dined with a sitting president.

The following year, in 1902, Church hosted Roosevelt at an auditorium he built in Memphis, where the president addressed a crowd of 10,000 Black citizens—the first time a sitting president directly spoke to Black voters. It was a watershed moment for African-American progress and respect at the ballot box.

The businessman also fought back against racial terror and its chilling effect on Black progress. All too often, when Black communities, towns or enterprises found success during Jim Crow, they faced brutal backlash—often in the form of nooses, gunfire or firebombing. Conservative estimates place total financial losses in the agricultural sector alone at $326 billion . Church knew this violence firsthand, of course, from being shot at his club in 1866.

Church became the first funder of journalist and sociologist Ida B. Wells’s groundbreaking research into lynching. He joined the Tennessee Rifles, an armed anti-lynching group, and helped Black families relocate from regions racked by racial violence. Perhaps most notably, after a local lynching shook up the Black community in Memphis he financed a group of Black Tennesseans to moving to what became known as Black Wall Street.

The bravery to build

Church exemplified how building Black America wasn’t just about capital—it was about the bravery to build political alliances and to face the violence that often accompanied economic and social progress.

When he died in 1912, Church’s fortune was estimated at $700,000 (more than $23 million in today’s dollars). But his wealth was never just personal. It was a weapon to create Black self-sufficiency in a hostile world. His homes anchored communities under siege; his capital funded Black enterprise; his storefronts gave entrepreneurs footholds in a segregated market; and his political alliances, sometimes with foes, ensured Black voices had a seat at the table.

As America marks 250 years since the Declaration of Independence, Church’s legacy proves Black economic power was no accident. It was built by entrepreneurs and activists like Church and Mary Ellen Pleasant, who picked up where the Freedmen’s Bureau left off, building infrastructure and opportunity for newly liberated people.

Studio portrait of Church. Photo: Church Family Papers/University of Memphis Libraries

Today, that legacy thrives. Black Americans’ spending power is projected to reach $1.7 trillion by 2030 , according to the McKinsey Institute for Economic Mobility. There were over 3.5 million Black-owned firms as of 2019, according to the Small Business Administration and the latest census data. Most of those are sole proprietorships, but nearly 135,000 are businesses with employees. That’s a testament to the groundwork laid by pioneers like Church.

Church’s legacy on Beale Street and beyond shows that even under the harshest conditions, wealth and power can be seized—and with them, a stake in America’s future.

Shomari Wills is a TV news producer, journalist and author. He is the author of “Black Fortunes: The Story of the First Six African Americans Who Survived Slavery and Became Millionaires.” He can be reached at reports@wsj.com .