How old is your pancreas? What about your brain or heart?

Scientists have come up with a way to estimate the age of organs, separate from the body’s age as a whole. They found in a recent study that many of us are walking around with at least one organ aging much more quickly than the others, and that older organs can indicate a greater chance of developing diseases.

Measuring organ age is the latest frontier in the world of biological age, the idea that your body’s physical age can be different from its chronological one. For example, a 50-year-old man hypothetically might have physical health that more closely resembles that of a 53-year-old, with, say, a 51-year-old heart and a 54-year-old brain.

Measuring organ age is the latest frontier in the world of biological age, the idea that your body’s physical age can be different from its chronological one. For example, a 50-year-old man hypothetically might have physical health that more closely resembles that of a 53-year-old, with, say, a 51-year-old heart and a 54-year-old brain.

Knowing the age of your organs might one day help you prevent and treat disease. In theory, if you knew that your heart was aging too fast, you could take steps to ward off heart disease .

“Heart aging predicts future heart disease, and brain aging predicts future dementia ,” says Hamilton Oh , one of the paper’s lead authors and a graduate student at Stanford.

Walking into your doctor’s office and getting a simple test to determine your organ age is likely still a ways off, but the concept is gaining interest among researchers, doctors and people focused on their own longevity and health. Scientists caution that more research is needed before such a technology might be ready for mainstream use. Some also say that parts of the recent study made too many assumptions.

Older hearts, higher risk

Most existing biological age tests , which various companies sell for several hundred dollars, work by measuring chemical changes in our DNA. Those tests generally give users a single number estimating their body’s biological age or rate of aging.

Attempting to calculate the age of specific body parts, like organs, goes a step further, and this latest study uses a different technique.

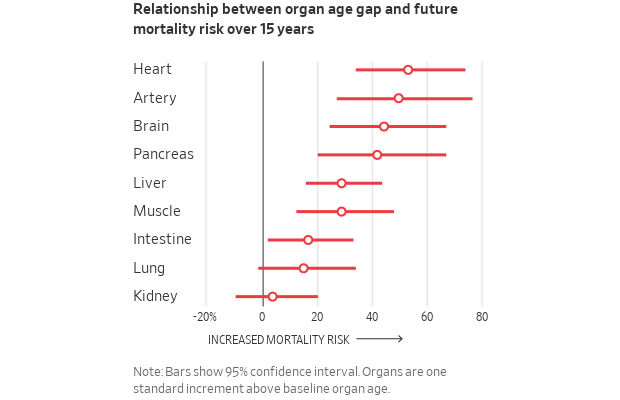

The recent study, published in the journal Nature in December, found links between older organs and health problems. An older heart, for instance, was linked to a higher chance of heart failure among generally healthy people. And older arteries and brains were associated with a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment.

People with hypertension, meanwhile, had kidneys that were about one year older than their same-age peers.

To find this, researchers associated different organs with certain proteins. They used blood samples to measure the levels of those proteins, which change with age.

They designed an algorithm to calculate the gap between someone’s chronological age and the ages of their organs. Roughly one in five relatively healthy people over the age of 50 has at least one organ that is aging much more quickly than the others, according to the study, which included more than 5,500 participants.

The gap, researchers found, could be used to predict how likely someone was to develop certain age-related diseases or die.

In the heart, for instance, every roughly four additional years of age was associated with a 2.5 times higher risk of heart failure over 15 years for healthy people. Healthy people with “older” brains had a 10% higher chance of developing cognitive impairment over the same period than those with “younger” brains.

“Understanding more holistically what is happening to someone with aging gives us a more personalized prediction in terms of that person’s individual risk,” says Morgan Levine , a former assistant professor at Yale who now works at a biotech company. Levine, who wasn’t involved with this recent study, has developed biological age tests, including one designed to measure organ-specific aging, using blood samples.

The Stanford researchers have co-founded a separate biotech company that has a blood test in development based on the research. They are working on a follow-up study with data from roughly 50,000 people from UK Biobank, a large health database.

Not yet ready for your doctor’s office

Scientists caution that more research is needed with a wider group of people before an organ-age test would be ready for mainstream use.

The links that researchers made between the proteins and organs aren’t clearly settled science, says Ben Orsburn , an instructor and principal investigator at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine whose research focuses on the study of proteins but who wasn’t involved in the study.

Before a test like this reaches patients, scientists should first figure out what treatments, such as drugs or lifestyle changes, can help people lower their health risks if they receive a high organ-age gap score, scientists say.

“It’s not going to be terribly helpful for someone to know they might arguably get a particular age-related disease early unless there are preventive steps or other interventions they can take to help that,” says Dr. James Kirkland , a physician and professor of aging research at the Mayo Clinic.

Doctors can already order targeted tests to assess the health of certain organs through protein measurements, such as liver function tests.

More advanced testing might one day lead to patients being able to tell through a blood test which organs are aging faster and start treatment years before chronic diseases like Alzheimer’s, diabetes or hypertension set in, researchers say.

“If that’s true, you don’t need to start taking biopsies of all different organs,” says Austin Argentieri , an aging researcher at Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital who wasn’t involved with the study.

Write to Alex Janin at alex.janin@wsj.com