Jennifer Maravegias has been applying for dozens of jobs, so she is ready for questions about work experience and salary expectations. A recent question on an online application stumped her, though.

“Check this box if you want to make sure this isn’t scanned by a machine ,” the laid-off project manager says she was prompted before submitting her application.

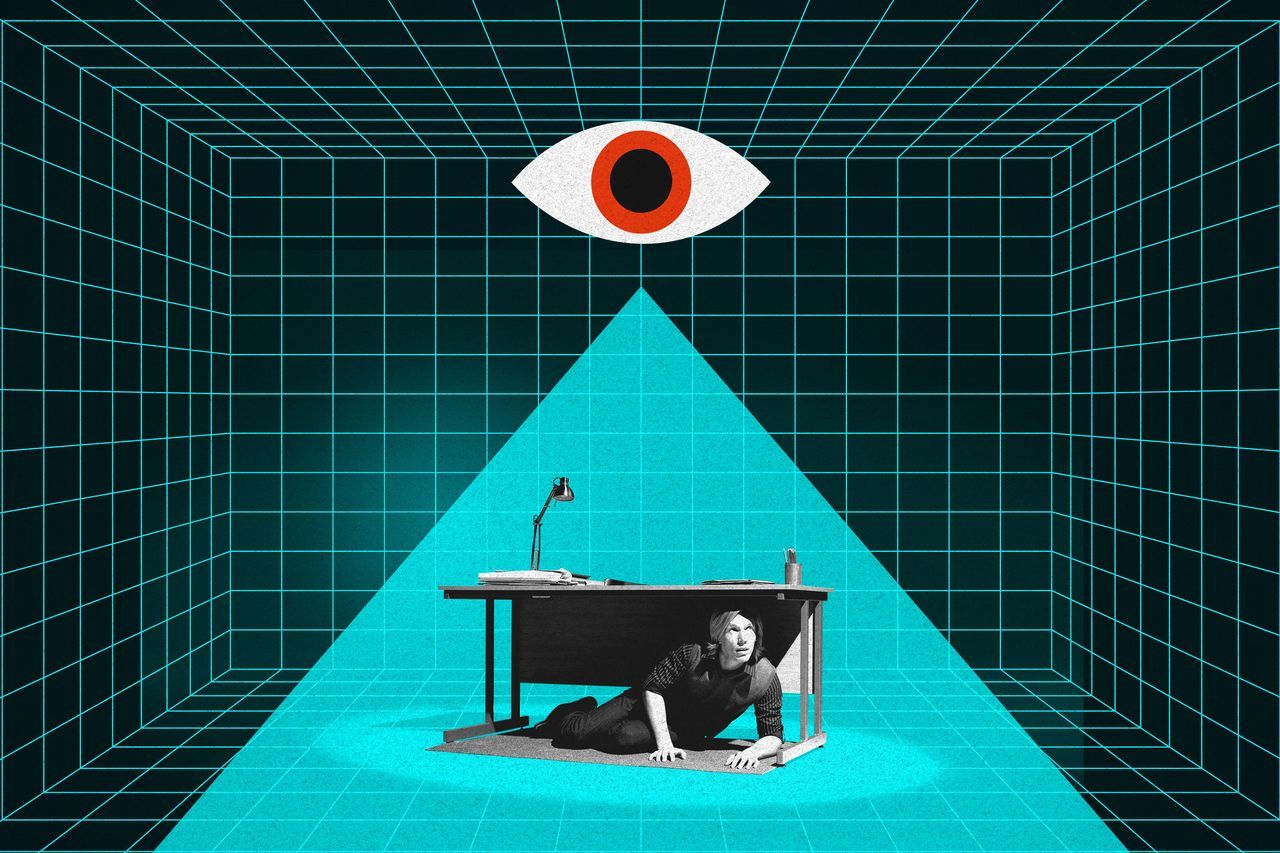

More job seekers in New York City can now request to opt out of letting artificial intelligence vet their résumés and job applications, thanks to a new law governing AI and hiring in the city. Some companies are extending the choice to non-New York applicants, too. But is skipping AI scrutiny a good idea?

Most major employers use some sort of automation to vet job applications, since companies often receive too many résumés coming in to manually review every one. Though efficient, algorithms can exclude qualified candidates or embed unintentional bias in hiring decisions.

New York’s law—the first of its kind in the nation—aims to bring transparency to the role of software in the job-application process. For any job based in New York, employers must disclose when AI is used to “substantially assist” in hiring and offer job applicants the chance to pass on such vettings in those cases.

But letting prospective workers forgo AI résumé reviews doesn’t ensure a human will review those applications instead, employment lawyers and researchers say.

Like Maravegias, many job seekers are unclear what the trade-offs of opting out are, and some are surprised that machines are reading their résumés at all. Months into her job search, Maravegias hadn’t gotten many bites and wondered whether opaque algorithms were hurting her chances . So she opted out, only to get zero response once again.

“I was still unemployed,” she says.

Anxiety over AI

Job seekers remain skeptical of AI’s role in the recruitment process. Two-thirds of U.S. adults said they wouldn’t want to apply for a job with an employer that used AI to help make hiring decisions, according to a 2023 Pew survey on AI in the workplace. The view was even more pronounced among women.

Jeff Sepeta, an IT manager in Chicago, works as a contractor who’s often moved from job to job in quick succession. Companies call him in to troubleshoot problems and move on, he says. But he fears that machines reviewing his résumé will judge him negatively if they misinterpret his short tenures, particularly when applying for noncontractor roles.

“At least when I’m dealing with a human I can explain,” he says.

Among Americans surveyed by Pew a year ago, more than 70% opposed allowing AI to make a final hiring decision, while another 41% opposed using AI to review job applications.

New York’s new rule, Local Law 144, requires employers using software to assist with hiring and promotion decisions—from chatbots that conduct interviews to résumé scanners that look for certain keywords—to regularly audit the tools for potential race and gender bias. Employers will also have to publish the results of those audits online.

The risk of not getting seen

Some employers argue that the New York law doesn’t apply to them because AI isn’t replacing the final human decision makers, said Emily Lamm, an attorney at Gibson Dunn. A Cornell University study of nearly 400 employers earlier this year was only able to identify 18 employers that had posted their audit results online, and even fewer that had posted notices informing job seekers about which automated hiring tools were being used and how to opt out.

For years, hiring software has helped employers winnow down what can be hundreds or thousands of applications to a smaller number of candidates who seem, at least on paper, best-suited to the role. Millions of qualified workers get screened out every year by automated tools that reject people for reasons like résumé gaps or failing to use the right combination of keywords , according to a 2021 Harvard study.

Yet opting out of AI vetting can hurt your chances of getting hired, because companies aren’t obligated to review all the applications they get, employment lawyers and researchers say.

“I’d say you’re more or less guaranteed not to be looked at,” said Joseph Fuller , a professor at Harvard Business School who was the lead author on the study.

AI-assisted screening could ultimately help many job seekers, Fuller said, noting that human-led hiring is also subject to concerns about discrimination.

Unless job seekers have a disability that qualifies them for an accommodation under federal or state disability laws, an employer doesn’t have to provide an alternate vetting process, said Niloy Ray, a lawyer who specializes in AI in the workplace at law firm Littler Mendelson.

“This is but a harbinger of things to come,” Ray said. “You may as well start figuring out how to address this.”

On the applicant side, many have already taken steps to navigate AI-driven hiring, paying for services and coaches that aim to help optimize résumés and make them an algorithmic match.

Know the pros and cons

Athena Karp, chief executive of HiredScore, which supplies AI-powered hiring software to employers, said that more than 80% of job seekers agree to the use of AI during the application process when its function is clearly explained.

AI can offer benefits to job seekers, Karp says, such as scanning for other job postings at a company that might match an applicant’s skills even when the person is rejected from the role initially sought.

The majority of HiredScore’s clients are offering applicants outside of New York City the ability to opt out of AI processing of applications, Karp says.

Robert Kerans, an IT manager based in Lake Bluff, Ill., said a recent experience left a sour taste in his mouth. He agreed to AI vetting while applying for a technology-support manager role at Accenture . He was rejected within 45 minutes. The speed of the snub made him question whether the system really worked, Kerans said, because he believed he was well-qualified for the role.

Accenture said that it uses AI to help inform its decision-making but that humans always have the final say on whether a candidate advances in the recruiting process.

Kerans said he’s happy to have a choice, at least, and has since chosen to forgo AI vetting.

“It can fail,” he says. “The reality is that having the human connection is more important.”

Write to Te-Ping Chen at Te-ping.Chen@wsj.com