Maria Damanaki, the former leader of Greece’s left-wing Synaspismos party, ex–EU commissioner, and current principal advisor to the international ocean conservation alliance Oceans 5 discusses the challenges of the green transition, Donald Trump’s impact on climate policy, the debate over hydrocarbon exploration, and whether dialogue with Turkey is inevitable.

Interview by Niki Lymberaki

For the past several years, Maria Damanaki has been dedicated to protecting the world’s oceans. In this interview, she speaks about her cooperation with the Greek government, the energy puzzle of the Eastern Mediterranean, and Greece’s complex relationship with Turkey. She also reflects on the dilemmas facing Europe’s Left, her years at the helm of Synaspismos—the coalition that eventually evolved into Syriza—and the approaching anniversary of the 1973 Polytechnic uprising, a defining moment in modern Greek democracy.

Some people believe that, like other top European officials, you cashed in your public career for a position with a major multinational corporation.

“Let me introduce myself properly. I am an advisor on climate and marine protection. I know the word advisor doesn’t always sound good in Greece—people tend to think we’re opportunists—but I do my best. I am the principal advisor to Oceans 5, the world’s largest philanthropic alliance for marine protection, which brings together some of the most important environmental foundations globally.”

We’re talking about the fight against climate change. How much does Donald Trump’s election affect all this?

“I was in New York when Trump came to the U.N. General Assembly and declared that everyone working on environmental issues is a fraud. But reality is unforgiving. Energy from renewables remains 40 to 50 percent cheaper than anything else. Last year, around $2 trillion was invested globally in renewables, compared with just $800 billion in oil extraction. Trump certainly has an impact, but he can’t reverse the current. That battle is already lost.”

And what about the European Union? It seems, let’s put it delicately, that its Green Deal targets are being scaled back.

“Europe is indeed, to put it politely, hitting the brakes on the green transition. The main reason, I believe, is that geopolitical and defense priorities have taken over. But the deeper problem lies in Europe’s lack of political integration.”

Recently, Mario Draghi spoke about the need for a ‘pragmatic federalism.’ Is that realistic?

“It’s not only realistic; it’s essential in my opinion. In this transactional age, power is what counts -nothing else. Integration is now more necessary than ever. And we need to move immediately on three fronts: the Capital Markets Union, Defense, and Energy. Energy, in particular, deserves attention because consumers are the ones footing the bill. But all of this hinges on one thing: the European Union must abandon the paralyzing rule of unanimity. I say this fully aware of the consequences this will have.”

Especially for smaller or less powerful countries like Greece.

“I believe Greece has what it takes to be in the fast lane, if we handle things wisely. We are on a growth trajectory, unlike some other member states, and we have long experience with how European institutions function. Even if we don’t have (unanimity), I believe that both our broader European interest and what we stand to gain as a country would still be greater by moving ahead with deeper integration.”

In your view, what should Greece’s role be today in the regional and European energy puzzle?

“Right now, Greece has a unique opportunity, thanks to its location and to the choices made by the Trump administration, to play a decisive role as a transit hub for natural gas. But there are many issues that need to be resolved for the “vertical corridor” up to Ukraine to function properly. American gas is expensive. Massive new investments are required for storage and regasification. Infrastructure projects are needed in many European countries. And we need full intergovernmental cooperation under the EU umbrella, something that does not currently exist. The fact that Europe still lacks a unified energy policy carries a huge cost for many countries, including Greece. Energy prices here are high, both for households and for industry.”

Is that mainly the result of Europe’s political deficit, or of distortions in Greece’s own domestic market?

“I would say it’s mainly a European deficit. There are, in essence, two Europes: countries whose energy mix relies on favorable factors, and others on the eastern and southern periphery that are at a disadvantage. So this is an opportunity for Greece to play a role as a transit hub. Some argue that Greece could also become a major producer. They predict drilling rigs will be operating within a year. I don’t share these rushed and exaggerated expectations.”

Drilling, Ms. Damanaki. One might assume this question is settled for someone who has devoted years to the green transition. Should Greece pursue hydrocarbon extraction or not?

“Extraction is not the solution, especially when we’re talking about the marine environment. The Eastern Mediterranean is an area of deep waters, and we don’t have a clear scientific picture of the reserves. Expectations are being cultivated that aren’t based on reliable data. However at this very moment, large American companies are showing strong interest, for reasons of their own and to serve their stock market needs. For them, exploratory activities in Greece are of negligible cost compared to their overall budgets. It would be difficult for any Greek government to refuse. What will ultimately happen, and whether any of this succeeds, we simply don’t know yet.”

Do you personally want these explorations to go ahead?

“I’m Greek. I must put the national interest first: to ensure Greece is not left out of the geopolitical game. Chevron and ExxonMobil, both active in Libya, are also interested in potential Greek maritime zones. If Greece wants to have a presence in the Eastern Mediterranean and maintain maritime zones, it cannot ignore this. So, although I am personally against extraction, I believe that at this stage, for geopolitical and national reasons, Greece cannot refuse the exploratory phase. As for drilling, that’s a discussion for later, if and when the data prove favorable.”

Would you see nuclear energy as an alternative path to cheaper power for Greece?

“I wouldn’t rule it out completely. Nuclear energy faces challenges of cost, safety, and waste management. Large-scale nuclear projects also require 10 to 15 years of preparation and massive investment, far beyond Greece’s capacity. But small modular reactors solve many of these problems. In my view, they shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. Still, we’re talking about the next decade, at least.”

Geopolitically, what is the goal of the proposed five-party conference?

“I think the Greek government’s initiative is the right one. Of course, certain conditions must be met: progress toward peace in Gaza, alignment of the initiative with Europe’s overall energy strategy, and, above all, a basic level of domestic consensus, so we don’t end up again in the familiar situation where one side accuses the other of national betrayal. If we meet those conditions, we could begin discussions on issues like environmental protection and migration and eventually move on to the crucial question of economic zones. In any case, I believe it’s time we finally woke up from our false sense of complacency and, sooner or later, had an honest discussion about what we actually want from our foreign policy.”

Haven’t we already answered that question?

“We’ve answered it, but in a way that I personally never found convincing. What we need, finally, is clarity from everyone. To put it bluntly: when you have differences with your neighbor, you can either resolve them through armed conflict, which I assume we don’t want, or through dialogue. So, there are only two paths left. One is the so-called path of inertia; the other is the path of initiative, which I have always supported. When does inertia benefit a country? Only when it can reasonably expect that, over time, conditions will change decisively in its favor. To be even more specific, and perhaps oversimplify, if we expect to become a technological powerhouse like Israel, or to experience a flood of investments that would enhance our soft power, or if we thought our neighbor would collapse, then inertia might make sense. But I see no such prospects. Inertia is also costly. We spend enormous sums on military equipment because as things stand, Greece cannot afford to be a defenseless nation. But how long can we sustain that arms race? And beyond that, there’s historical memory -something defenders of inertia tend to forget. Who was the first to say that the International Court of Justice could provide a solution? Konstantinos Karamanlis.”

But can Greece—its government or a prime minister—really say, “I will discuss our territorial waters”?

“No Greek prime minister could ever negotiate away our existing territorial waters at six nautical miles. That’s a matter of national sovereignty. The question of a possible extension up to twelve miles, as provided by international law, is something else entirely. I emphasize up to twelve, not at twelve, as some say. This is an exercise of a sovereign right, and something we can and must discuss. How else will we move forward? Let me remind you that in 2003, the Simitis government came very close to a solution but ultimately chose not to bear the political cost and didn’t proceed with it. I had the chance to speak with the prime minister at the time and told him clearly that leaving the issue unresolved was a mistake. Of course, it was his personal decision as a leader, which I respect. But Greece missed an opportunity.”

Do you believe that any prime minister who reaches such an agreement would be committing political suicide?

“Indeed, they would pay a heavy political price. But would it be so terrible for a leader to decide that, for the good of the country, they might not be re-elected? The real issue is to prepare public opinion.”

What does that preparation involve?

“During my years in Greek politics, I often encountered the same phenomenon, which I suspect still exists. Many serious people would tell me privately that they agreed with the positions I took, but when they appeared in public, they showed a completely different face. At some point, we must stop doing that. We need an honest national conversation, free of taboos and sacred cows.

What are those taboos?

“In Greece, taboos exist where you least expect them. Take the idea of dialogue, it’s practically demonized. The notion of compromise is treated as shameful. I think this stems from the legacy of the Civil War, which still lingers. I remember it well from my years in left-wing politics. I once said that the great problem of the Greek Left is that it clings to its purity test, its “left-o-meter”: always competing over who is the purest leftist. And so it keeps shrinking, like an amoeba endlessly dividing in search of what it believes to be its true and authentic core.”

The Left does that with its purity tests. What about the others?

“They have their own purity tests, their “right-o-meter”. “They do the same with patriotism—treating it as something to be measured. Patriotism is, of course, a noble sentiment, one each person experiences privately. But it’s tested only in difficult times”.

Marine parks are your area of expertise. Minister Akis Skertsos recently acknowledged your valuable contribution in a public post. What kind of collaboration do you have with the Greek government?

“Our cooperation began when John Kerry and I persuaded the Greek government to host the Our Ocean conference, and it has continued ever since. I work with the government on behalf of Oceans 5, meaning that I bring in international experience and share best practices from around the world. Obviously, I’m not paid, nor do I hold any formal position within the Greek government. I should add that I would gladly do the same for any Greek government. And I’d be equally happy to collaborate with any other democratic political force that was interested and asked for my help. I’m here—and waiting.”

Have other parties approached you? For instance, has Syriza ever reached out to Maria Damanaki?

“They haven’t shown much interest so far. I hope they will in the future. We’re here. Our door is open.”

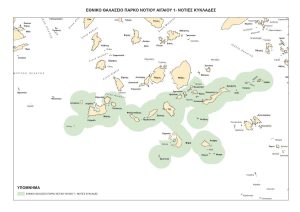

Why were the Dodecanese islands excluded from the final design of the marine parks?

“At some point, we’ll have a marine park there as well. The decision to start with the Southern Cyclades was strategic: it allows for a unified park with room for future expansion. Once the parks in the Aegean and the Ionian Seas have been established, Greece will exceed its ‘30×30’ target— even protecting 35%t of its marine areas once these projects are implemented. That would place Greece at the forefront of marine conservation in Europe.”

Several observers suggested that the Dodecanese were excluded to avoid provoking reactions from Turkey.

“At this point, the Turkish government cannot reasonably object, since the marine parks are entirely within Greek territorial waters. If it were to raise such objections, it would be escalating tensions with Greece to another level. And I don’t think that’s their current intent. On the contrary, the most recent statements by Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan point to the opposite direction.”

Are issues like marine parks potential fields of cooperation with our neighbors? Could a joint park be possible?

“I would personally welcome it, and if it is ever realized, I’ll do everything I can to help. We could move forward with a joint initiative for marine protection in the Aegean. A shared park could be much larger in scope, extending beyond the territorial waters of both countries. At the moment, we have Greek waters, Turkish waters, and an intermediate zone where no specific uses have been defined. That area could become a starting point for cooperation.”

What’s your view of where the Left stands today?

“I’m not in a position to give lofty advice. I don’t live here full-time, and there are younger, better people to take on that role. But I can’t help making a brief comment, especially after the success of Mahmood Mamdani, who reminds us that the Left can free itself from the burden of grand visions and focus instead on concrete issues that truly speak to citizens’ concerns.

Looking back on your years leading Synaspismos, is there anything you regret?

(Synaspismos /The Coalition of the Left, of Movements and Ecology was a Greek left-wing political party, founded in 1991. It eventually became part of SYRIZA)

“I made serious mistakes and because of them, Synaspismos failed to enter Parliament. Do you remember that 2.95 percent? The fact that I resigned, and took full political and personal responsibility, doesn’t really console me. My greatest mistake was that I, too, was trapped by the Left’s own self-imposed constraints. One of those I mentioned earlier: the obsession with the ‘grand vision.’ Another is the fixation on collectivism. I didn’t have the courage to make certain decisions and move forward with those willing to follow them. Perhaps things would have turned out differently for Synaspismos, if I did. Perhaps not. Who knows?”

Would you ever return to what we call frontline politics?

“Not a chance! There are others who can do the job better, and I’m doing something that I truly love.”

We’re only days away from the anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising. Why have you chosen not to speak about it publicly or to take part in commemorations?

“Because the student uprising at the Polytechnic was something immense, and deeply collective. My role was not what some people imagine. Besides, I have no additional information to reveal. So much has been written and said about that time. And anyone who wants to know can. I have nothing more to add. I’ve already said everything I had to say, through my actions.”