With unseasonably high temperatures and the Greek tourist season kicking off early this year, beaches in Greece are filling up, “and the difficult balancing act that we perform each year at Schinias beach has already begun,” Eleni Katsirodi, Head of the Management Unit for Attica’s Protected Areas told To Vima.

The Contradictory Nature of Schinias-Marathon National Park

Schinias beach is located northeast of Athens and is part of the Schinias-Marathon National Park, which boasts one of the last three pine forests in Greece with Pinus pinea and halepensis pines, a priceless marshland that two thirds of all migratory birds passing through Greece make a stop at, the important Markaria Spring, and unique flora and fauna.

Yet, given the active farmland, beachfront villas amidst the pines, and even an Olympic rowing center with an adjacent hotel, visitors would be forgiven for wondering how a national park allows so many activities that seem in conflict with conservation efforts.

Katsirodi explains, “The region was made a national park in 2000 by Presidential Decree 395/2000 to protect it from further deterioration and development. The farms, houses and businesses were already there, so there was not much we could do about them.”

By Arne Müseler / www.arne-mueseler.com, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=85236349

“The Olympic rowing center and hotel were built around the time of the decree, which may seem like a conflict because it necessitates permanent interventions to the landscape, but the presence of water year-round has actually proven a boon to wildlife,” says Katsirodi. To accommodate bird populations, all lights are turned off at night, only kayaks and canoes are allowed, and races are staged only after the birds’ reproductive cycle is complete.

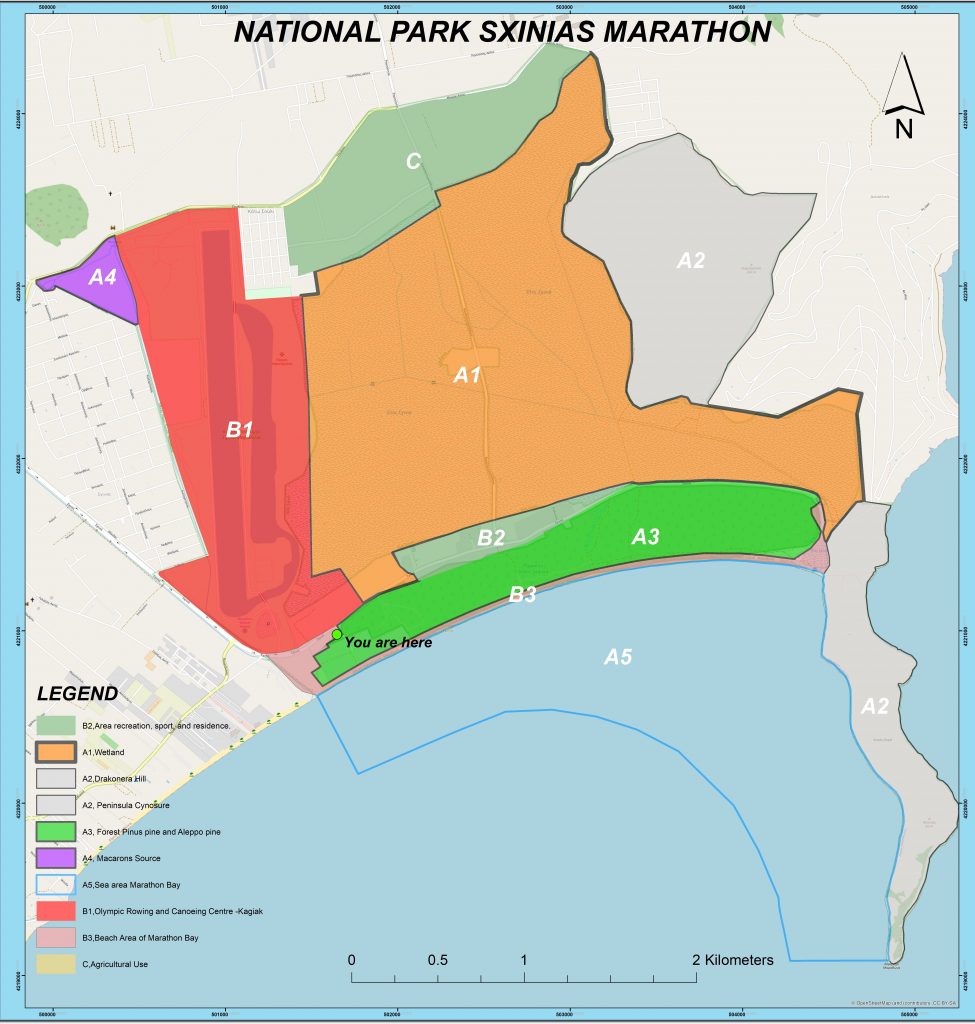

Today, the Schinias-Marathon National Park is divided into ten zones between the sea in Marathon Bay and the Olympic center, with one of three levels of protection assigned to each. With its Umbrella and Aleppo pines, the Schinias Pine Forest (depicted as area A3 below), enjoys the highest level of protection.

The Conflict with Local Society

Schinias doesn’t usually make it on the bucket list of tourists, but rather, it is frequented by middle class families and Athenians looking for an affordable respite from the bustle of the city.

For decades they could be heard honking their way through the narrow, winding dirt roads along the beach, parking in the shade of pine trees, laying out their blankets and picnicking by the beach – for free.

Bulldozers cleared the beach of Schinias every spring to remove dead Posidonia seagrass, illegally built tavernas served up fresh fish on the beach, and the beach and forest itself were often littered with trash.

That is until a few years ago, when metal bars were installed to stop cars entering Schinias’ protected forest and the beachside tavernas were demolished.

“The decision was hard to explain to the local community. Pinecones fall straight onto the ground beneath the trees, so when the cars drove over them, it stopped new trees being born,” explained Katsirodi.

“We also faced the threat of fines from the European Union for the activities in the forest zone, along with the risk of forest fires. It would have been impossible to evacuate people from the park if there was a fire.” But it wasn’t until the fires of Mati in 2018, which killed 107 people, the people started to take public safety concerns seriously, she added.

Regenerating the Pine Forest and Beach

After just a few years of restricting access to the forest, visitors who stroll down the beach towards the protected forest and explore the coastal zone will see noticeable changes.

The taverns are gone, the beach and forest are clear of visible debris and cars, hard and soft mounds of dead seagrass lie matted on the beach, and fenced-off young trees can be seen in the forest.

Katsirodi says they immediately started planting indigenous pines where the taverns used to be, “but in just two years the forest started regenerating on its own. We now have 60 fenced-in areas with new trees.”

Three pilot regions of around 1.5 hectares each are monitored by the Institute of Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems and Forest Products Technology. Genetic tests have been performed on the indigenous pines of Schinias and researchers have discovered that they are uniquely resilient to climate change.

As a result, there are even plans to use part of the park to develop a nursery for Schinias pine trees, which will then be used to help reforest other regions in Greece.

The most eyebrow-raising change, though, is the dead seagrass on the beach. Still, a curious visitor with quick wit will grasp the seagrass’ importance.

POSBEMED, an EU-funded project on the sustainable management of beaches that receive influxes of dead Posidonia seagrass in the Mediterranean region, discovered that the withered leaves, fibers and rhizomes combat beach erosion by reducing wind and swell wave energy, and building dunes.

The evident success of the project has put the breaks on the annual visits of the bulldozers, which also inadvertently removed tons of beach sand along with the seagrass. Now Greece is stopping the practice in other regions of Attica, as well.

Working with the Community

Still, the visible success of the restoration efforts merely dampen the grumbling of locals who want free beach access, as inflation continues to hit wallets and the movement against sunbeds and umbrellas culminated in the Greece-wide “Towel Movement” last summer.

Further down the beach, access to the beach is blocked by beach tavernas which charge an entrance fee to access their facilities, while parking on the narrow main road is forbidden. In search of a compromise solution, the park service has entered into discussions with the local mayor to arrange a beach bus that will shuttle beachgoers between the Olympic rowing center carpark and Schinias beach.

Meanwhile, the “Paralies” adopt-a-beach program (‘paralies’ means ‘beaches’ in Greek) operates on the beach during the high season from June to mid-September.

For the past three years, Schinias beach has been divided into four 750m-long sections and adopted by, respectively, AVIN SA, PPC SA, Vassia Kostara Limited Collections, TERRA NOVA Ltd and Fiber Loop PC.

In essence, the companies cover Paralies’ operational costs, which range from 15,000 to 20,000 euros per section, and include installing and collecting waste bins, recording categorizing transporting and disposing of waste, reporting on waste to the Hellenic Ministry of Environment and Energy, staging awareness-raising campaigns with citizens and beachgoers and, of course, the cost of consumables and the salaries of the trained staff who visit the beach twice-daily to remove trash.

Chemical Engineer Ioannis Spanos of Paralies says the program has been a tremendous success with the local community and as a project. “Beachgoers are very enthusiastic and ask the staff cleaning the beaches a lot of questions. We have been cleaning the beaches twice a day every day throughout the summer for three years now. Families who have been visiting the beach for years have seen us at work, watched the beach get cleaner, got educated and changed their behaviors.”

In three years, Paralies has removed a whopping 6,900 kg of plastic waste, 2,683 kg of paper waste, 4,457 kg of glass, and 12,622 kg of mixed waste from the beach.

A New Presidential Decree

The farms that form part of the park do not use organic farming methods, so the run-off from pesticides goes directly into the sea.

This causes an undetermined level of harm to the aquatic environment in general and the priceless Posidonia sea grass beds in particular, which act as carbon sinks, fish nurseries and more.

However, according to the management of the National Park, there is no way to oblige farmers to change over to organic farming, which is expensive, labor intensive and requires training.

A new Presidential Decree is, however, under public consultation and will—it is hoped—address some of the more entrenched problems surrounding conservation and protection in the area. But the jury is still out.

Is the ICZM Protocol a Solution or Another Problem?

Some say that what Greece really needs to do to protect its precious coastal zone areas, like Schinias, is to ratify and implement the United Nation’s Environmental Program protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM).

ICZM is a process that promotes the sustainable management of coastal zones from the sea to the coast by looking at the coastal zone as one integrated area, as opposed to a piecemeal land versus sea approach. The latter approach is often criticized for resulting in conflicting uses of the land-sea interface in coastal zones and burdening ecosystem services. But, while Greece signed the protocol in 2008, it has yet to ratify it.

The General Secretary for Natural Environment and Waters at the Greek Ministry of Environment Petros Varelidis had this to say, “I don’t foresee Greece ratifying the ICZM in the near future. Greece already has a very restrictive building framework for the coast and the scale of our landscape is different from that of Spain or Italy, and this needs to be taken into account.”

ICZM restricts building within 100 meters of the coast, “and while this isn’t a problem for the west coast of the Peloponnese, it may be for a small island. When you have steep cliff, why should you be restricted from building a hotel on it overlooking the sea?”

Putting this in perspective, Varelidis adds, “If these were the rules in the past, Santorini would not exist today. It is not that we want to develop all of the coast. On the contrary, we love the environment and want to protect it. But there is no one-size-fits-all approach. We need something tailor-made for the uniqueness of Greece.”

This article is part of a special thematic series covering key issues related to the 9th Our Ocean Conference, which will be hosted by Greece this year and held in Athens from April 15–17 at the Stavros Niarchos Center.