How do you truly appreciate an ancient artifact, or understand the urgency of its return to its homeland, if you’ve never even seen it? That is the paradox UNESCO seeks to address with its groundbreaking new project: The Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects.

Three years after it was first announced at MONDIACULT 2022, the initiative was unveiled this week at MONDIACULT 2025 in Barcelona. The museum opens its doors not in a city, but everywhere at once: a global, immersive platform where looted treasures are finally given back their stories — until, one day, they are given back for good.

A Museum Designed to Disappear

In most museums, the collection expands with every new acquisition. Here, the goal is the opposite. This museum will shrink. Each object added is one that has been stolen, looted, or illicitly trafficked. As restitution takes place, the digital display will vanish — symbolizing that justice has been served and the artifact has returned home.

“When an object comes home, a story can begin again,” reads the welcome message in the Return and Restitution Room, a dedicated section showcasing successful cases of cultural repatriation.

The Architecture of Memory

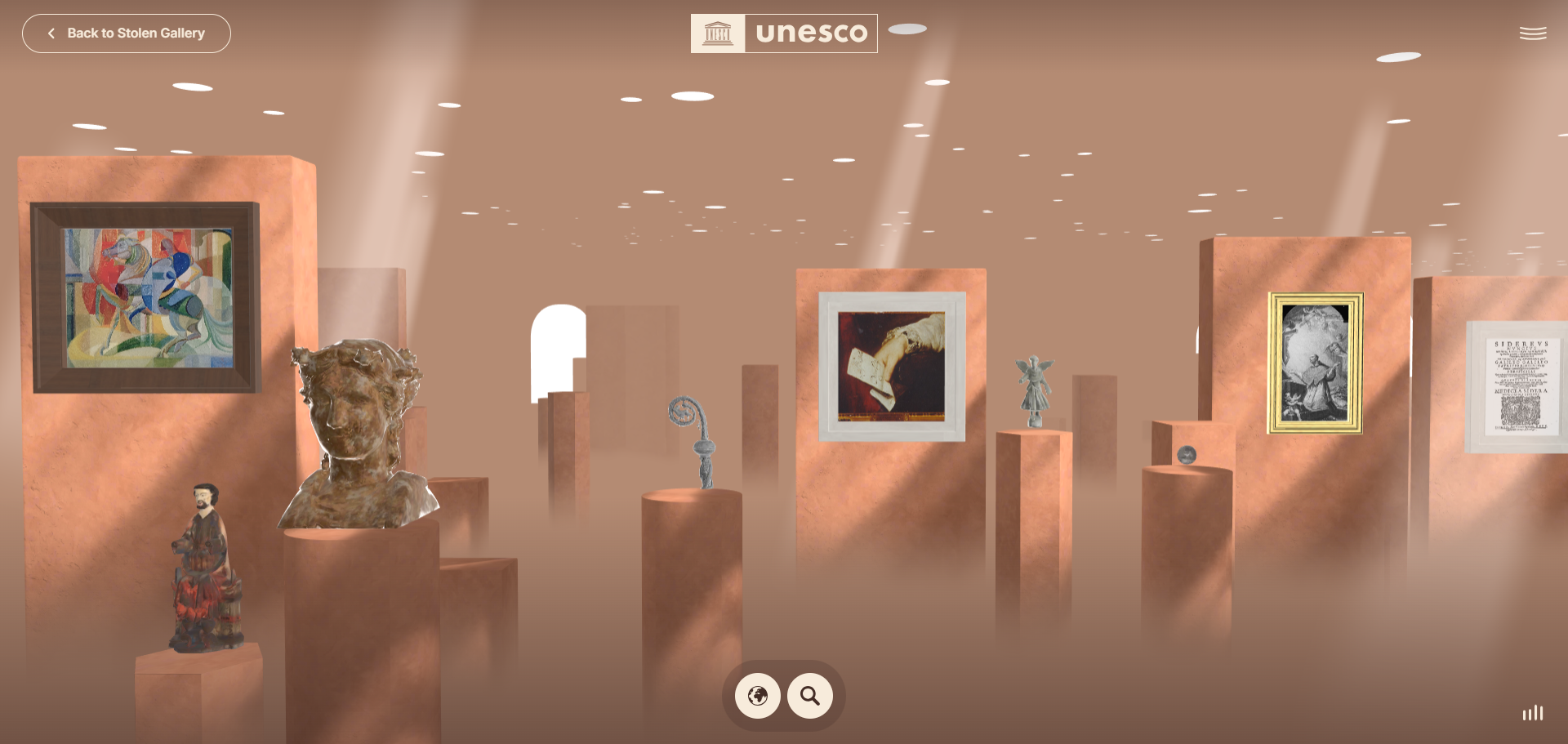

The museum’s design, by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Francis Kéré, evokes the baobab tree — a resilient, deeply rooted presence in African culture. Inside this symbolic space, exhibitions combine digitized artifacts, interactive tools, and even VR experiences, bringing visitors into direct dialogue with objects that were taken from their original communities.

Visitors can explore more than 250 cultural objects from 46 countries, searchable by region, date, or origin. From rare books to Cycladic figurines, from Southern African heritage to ancient Greek offerings, every piece is accompanied by the story of its creation, theft, and enduring significance.

Nine Greek Voices From the Past

Among the museum’s 277 registered items, nine belong to Greece — a poignant reminder of how deeply the country’s cultural heritage has been affected by looting.

The journey begins at Olympia, with a miniature bronze cauldron dating from the late 9th century BCE. From the same sanctuary, but crafted in the late 8th century BCE (the Geometric period), comes a small bronze figurine, likely a votive offering at the Great Altar of Zeus.

From prehistoric Thera (Santorini), two vessels dating back 3,600 years tell the story of early Aegean civilization: a drinking vessel decorated with black-and-white motifs and an olive oil or wine container, both unearthed at the settlement of Akrotiri.

Five of the nine pieces are depictions of women. Among them, two Cycladic marble figurines from Naxos, dating to the Early Bronze Age (3000–2200 BCE), stand out as timeless emblems of the islands’ artistic language. From the wider Cycladic world also come a limestone statuette of a goddess associated with childcare — likely dedicated at the sanctuary of Aphrodite near ancient Thera — and a marble female head from Paros. The latter may represent either a kore, the archetypal young maiden of Archaic sculpture, or a sphinx, with its painted eyes once bringing the hybrid creature to life.

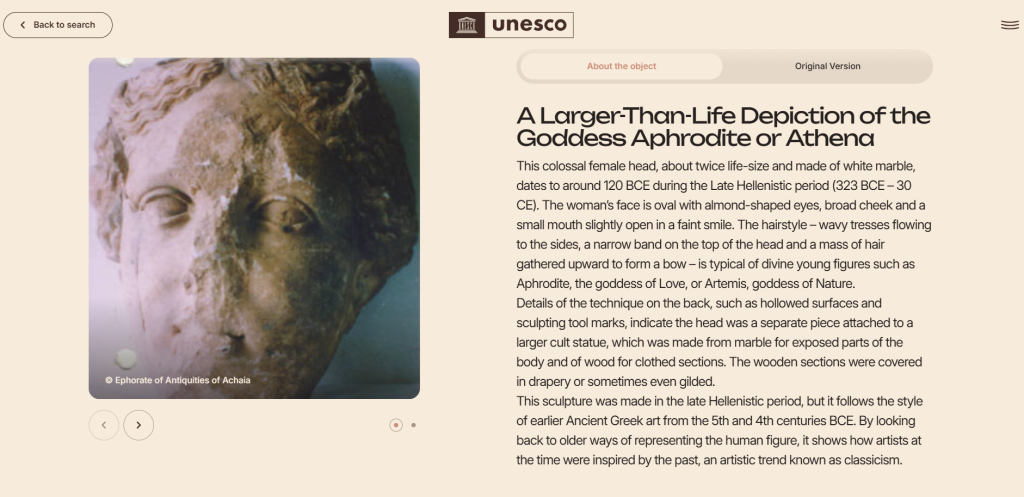

The final piece is monumental: a colossal female head, about twice life size, attributed to either Aphrodite or Athena. With its almond-shaped eyes, broad cheeks, and faint, enigmatic smile, the sculpture was discovered in 1987 at the ancient Theatre of Aigeira in Achaia during excavations by the Austrian Archaeological Institute.

Technology, Testimonies, and Justice

Harnessing 3D modeling, virtual reality, and testimony from affected communities, the Virtual Museum isn’t only about objects. It’s about people. It’s about stolen identity, interrupted memory, and the possibility of cultural renewal.

Supported by Saudi Arabia and developed in collaboration with INTERPOL, the project is the first of its kind — a global effort to not just document stolen heritage, but to return it.

UNESCO has long championed restitution as a matter not only of ownership but of dignity, justice, and identity. “A restitution process often goes beyond the act of physical restitution,” the organization notes. “It encompasses the restitution of knowledge, a strengthening of cultural or scientific cooperation, and a renewed dialogue between communities.”

In this light, the museum is both an archive and an act of resistance. Until the day these objects go home, they remain here — not in silence, but with their stories told.

View this post on Instagram