The survival of the Hellenic Post does not depend on the communication strategies of this government, the next one, or any other that comes and goes — nor on the emails that were meant to “inform” the political leadership and got lost along the way, unread. It depends on their adaptation to the modern world.

With the bugle, the leather satchel with two straps, and the cart that sets off lazily from an abandoned post office? Or with every tool that the digital age provides?

It hardly matters anymore whether the Post belongs to the Superfund, whether its management is overly technocratic and lacking the political sensitivity that regional MPs have in abundance, or whether the investor carries a Greek passport. What truly matters is whether ELTA — which once made history with rare stamps and postcards that reached their recipients decades later — will become part of a national and state entity that offers better services to its citizens.

That is where the importance of the endeavor lies. ELTA is one of those national acronyms which, even when devalued, never lost their special weight. The measure of their success does not lie in the market and its self-regulations. This is the difference between them and private couriers, private clinics, or private schools. The bar is set elsewhere — and it is national.

Do we have a state with good post offices and hospitals, good schools and universities, good transport, and even better public services such as electricity and water?

Or a chaotic state that wounds our national self-confidence because “nothing ever changes” in a daily life of hardship and insecurity?

In other words, what matters is the method and the “model” that ensure letters, parcels, and pensions arrive on time — and especially in the provinces, that the sense of an absent state does not weigh down citizens. That sense is certainly worse than even a broken-down state.

The state does not need to be present through idle employees watching the seconds tick by on a wall clock. It can be present through vans and tablets — as long as it is present.

As long as Hermes flies — and flies as fast as the couriers, if not faster.

In the years before the financial crisis, two rigid schools of political thought clashed in this country. One claimed that the state — that is, the taxpayers — must bear the cost of its services, whatever that may be. The other claimed that the state is, by definition, a failed entrepreneur.

It was a battle between a statism that denounced every privatization as the “selling off of the family silver,” and a blind faith in the market that read only balance sheets, believing that even the air we breathe could be traded. Both were proven wrong — but in the meantime, the state went bankrupt. And it went bankrupt precisely because it failed to adapt to the flexibility offered by alternative business models, later adopted — after paying the price — by various public enterprises. At least, those were saved.

Today, the Hellenic Post is not threatened so much by the government’s communications fiasco as by its political consequences. Some MPs see salvation for abandoned post offices in philately; others denounce “dark plans of privatization and sellout by technocratic managers.”

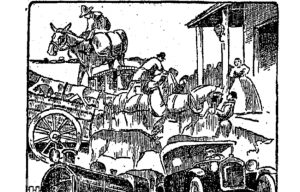

It’s not just Hermes. It’s also the public discourse — returning to the era of the oxcart.