Greece’s pension system is navigating a precarious balance between immediate social protection and long-standing structural deficiencies. The €409 monthly support payment for older citizens represents a temporary lifeline for those excluded from contributory pensions, yet it also exposes the limits of fragmented policy. The most recent December 2025 Pissarides review, a KEFiM-led initiative, provides the most recent assessment of these challenges, emphasizing systemic complexity, coverage gaps, and sustainability risks. This appraisal is a result of my association with the pension side of the review and highlights aspects such as the urgent need to connect short-term relief measures with comprehensive reforms that can secure dignified and fiscally sustainable retirement for all Greeks.

Short-Term Support Measures

Renewed attention has been given to the non-contributory support for uninsured elderly residents, who receive a monthly payment of €409 if they are over 67, meet income thresholds (€4,320 for singles, €8,640 for couples), and comply with asset limits. Although often described as a recent initiative, this benefit is grounded in Article 93 of Law 4387/2016, with the current level taking effect 1 January 2025 (Oikogeneia.gov.gr).

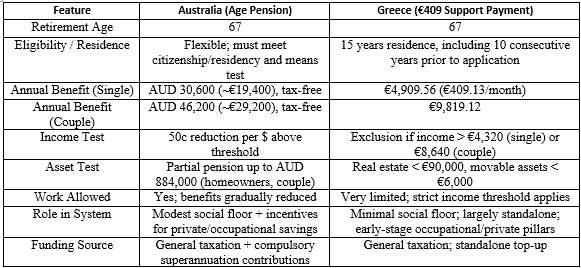

This payment provides an essential poverty-prevention function, ensuring vulnerable retirees are not left entirely without income. Yet it is insufficient to support a dignified retirement. In contrast, there are similarities with Australia’s (government funded) Age Pension which delivers a modest but adequate standard of living, complemented by mandatory private superannuation savings (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority). A short comparison between the two is presented here:

The table illustrates that while Greece’s €409 payment incorporates some Australian design principles, it falls far short in adequacy, scale, and structural support. Furthermore, Greece’s public pension system is also among the most costly in the OECD, with spending on old-age and survivor benefits reaching approximately 16% of GDP (OECD, 2025). This reflects the reliance on a pay-as-you-go system, broad coverage, and relatively generous benefits relative to contributions. By contrast, Australia’s public Age Pension represents under 4% of GDP, due to the system’s design: a modest government-provided safety net complemented by compulsory private superannuation savings (OECD, 2025). This stark contrast highlights how the structure and balance between public and private retirement income influence fiscal sustainability, underscoring the challenges Greece faces in aligning pension adequacy with economic prudence.

Long-Term Reform and System Modernisation

As highlighted during the 6th Occupational Retirement Provision Forum by John Livanas, Steve Bakalis, and George C. Bitros (To Vima), Greece’s pension system increasingly resembles a malfunctioning operating system: fragmented rules, overlapping entitlements, and opaque administration continue to undermine efficiency, reduce transparency, and erode public trust.

Simplification would reduce bureaucracy, lower government expenditure, and clarify entitlements. Beyond administration, full state responsibility for pensions risks violating basic economic principles. Under the identity S + T = I + G (private savings + taxation = private investment + government spending), excessive reliance on the public sector can crowd out private investment, weaken incentives, and jeopardize fiscal sustainability—a dynamic brutally exposed during the 2009 crisis. High taxation, bureaucratic opacity, and a shadow economy estimated at 20–21% of GDP reinforce these risks.

TEKA, Greece’s funded, defined-contribution scheme, responsible for citizens’ pension savings, remains largely parked in low-risk holdings at the Bank of Greece, reflecting early-phase caution. Its current monopoly structure limits competition, governance quality, and innovation. International experience suggests multiple providers, professional boards, and independent asset management are necessary for robust second-pillar functioning. Reforming TEKA would strengthen retirement security, reduce long-term fiscal pressure, and rebalance responsibility between state and citizens.

Long-Term Sustainability and the Pissarides Review

The recent Pissarides Commission’s evaluation under the auspices of KEFiM identifies pension reform as central to Greece’s long-term economic resilience. The review is clear: short-term interventions cannot substitute for structural reform. Greece therefore requires a dual strategy as short-term measures like the €409 payment protect vulnerable citizens today. These measures must feed into a reform pathway that:

- guarantees a minimum standard of living,

- simplifies administration and reduces bureaucracy,

- reforms TEKA toward a multi-provider, professionally governed system,

- strengthens occupational and private pension participation, and

- aligns public responsibility with sustainable macroeconomic principles.

Without this alignment, temporary lifelines risk becoming permanent stopgap measures—repeating the dynamics brutally exposed during the 2009 financial crisis, when an inadequate and fiscally unsustainable pension system amplified macroeconomic imbalances rather than cushioning them.

By contrast, during the same period, countries with well-developed private and occupational pension pillars—most notably Australia—were better insulated, as accumulated private retirement savings acted as a stabilising buffer for households and reduced pressure on public finances. As of late 2025, Australia’s compulsory superannuation system had accumulated AUD 4.4–4.5 trillion in retirement savings, one of the largest funded pension pools globally.

Conclusion

The €409 monthly support payment is a necessary short-term measure, but it is not a structural solution. As the December 2025 Pissarides review emphasises, pension reforms is an area where progress has been slow, with some urgency for Greece to transform temporary interventions into enduring reforms: simplify administration, reform TEKA toward multi-provider governance, strengthen occupational and private pillars, and align state responsibility with sustainable macroeconomic principles. Only then can Greece secure dignified, sustainable retirement outcomes while avoiding the fiscal fragility that has plagued its system for decades.