The first kiosks appeared on the streets of Athens in 1877. Only a few decades had passed since the shedding of the Turkish yoke, and the newly founded Greek state, a colorful mosaic, was trying to find its bearings, shape its identity, and gain international recognition. It was then that the Mayor of Athens, Timoleon Filimon, installed the first kiosk in Syntagma Square for reasons of… beautification: a polygonal kiosk purchased from Switzerland for 15,000 drachmas. Another followed in Omonia, the next in today’s Vathis Square, and then in Varvakeios. From then until today, kiosks became identified with the Athenian landscape, bore witness to the city’s history, and followed its evolution, having much to tell.

View this post on Instagram

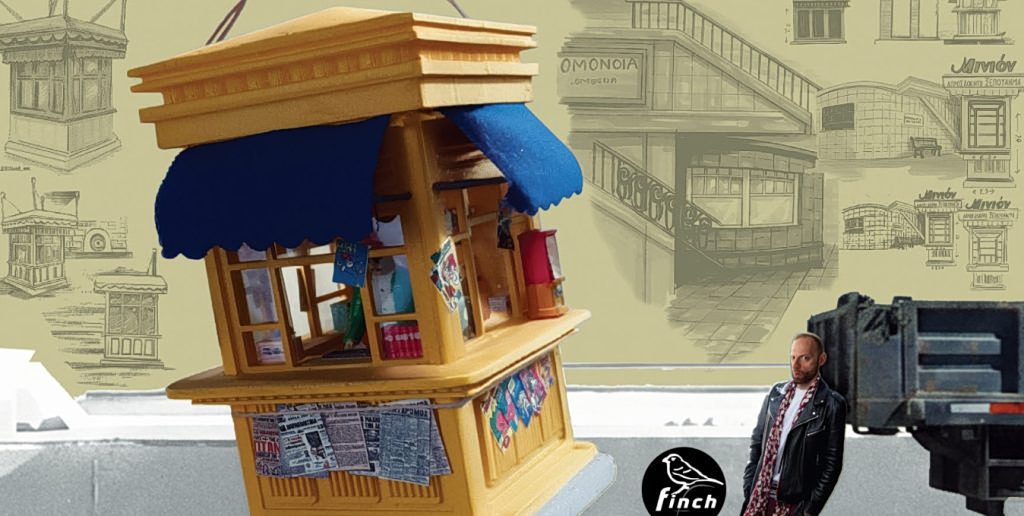

A nostalgic journey through the history of the Athenian kiosk, guided by art, is offered by a unique exhibition currently being held in Athens. Legendary kiosks—such as the kiosk of the famous… Koutalas on Vouliagmenis Avenue, where transactions were carried out using a long ladle; the small “Minion,” which was the forerunner of the large department store on Patission Street; and the kiosk on Panepistimiou Street that collapsed in 1997 during works for the construction of the metro—come to life through the hands of visual artist Andreas Finch.

In the form of a “game”

There are 20 three-dimensional representations of real Athenian kiosks, measuring 25 x 25 cm, made using a combination of materials: plastic from a 3D printer, wood, balsa, and cement. “This exhibition emerged after long-term research and presents the gradual course of Athenian kiosks from the beginning of the previous century to the present day, with emphasis on their historical, architectural, and folkloric evolution over time,” he himself tells TA NEA. Being a collector of old Greek toys, he realized at some point that although he owned toys depicting characteristic Greek professions, such as the Athens–Piraeus bus driver, there was not a single kiosk. “So I decided to design one myself in the form of a ‘toy.’ I relied on old photographs, postcards, and archival material that I had been collecting for many years, and this effort eventually led to the creation of the exhibition,” he says.

In this way, emblematic kiosks are revived, such as “the blue kiosk on Karagiorgi Servias Street, which few remember today. It was built in 2000 and was blue with little stars on the roof,” says Andreas Finch, “as well as historic kiosks such as ‘The Muses’ in Omonia Square, which are connected to a very interesting story,” he continues. “In 1934, when the electric railway station at Omonia was moved underground, the authorities decided to open eight ventilation shafts around the perimeter of the square. They then had the idea of placing kiosks—that is, newsstands—at the base of the shafts and statues of the Muses on the roof. Of course, there were eight shafts and nine Muses, resulting in one being left over, and that was Calliope. Thus Athenians jokingly said that Calliope was in the basement, where the public toilets were located. And the name Calliope became associated with them…”

Particularly interesting, according to Andreas Finch, is that “each kiosk is a different world. A kiosk in Perama sells completely different things and is set up in a completely different way from a kiosk in Kifissia. Kiosks reflect architectural evolution, social changes, and the needs of each era.”

Moreover, as Thanasīs Kappos, journalist and author of the books The History of the Greek Kiosk and The Kiosks of Athens, points out, “over the years kiosks became an institution. An institution that, despite problems and difficulties, continues to be a point of reference for Greece, ‘illuminating’ the streets of every city and village in every part of the country. A true beacon.” The well-known chronicler of the early 20th century, Sotiris Skipis, wrote in an article in the newspaper SKRIP on October 20, 1919, about the kiosks that appeared in Athens: “Worthy of congratulations is the Mayor who decided on the erection of many kiosks in Athens, which he will grant to war wounded or to members of fallen soldiers. One cannot imagine how many good things will immediately result from the erection of kiosks. The kiosks will be an ornament to the city, they will serve the public, and many disabled veterans of the two wars will find a means of livelihood. Through this medium Greek printed matter—whether newspaper, magazine, leaflet, or book—will spread. And they will be the cause for our large provincial cities to stir a little and imitate the capital a little.”

“This is a highly vivid depiction of the role of kiosks in Greece over the following 90 years,” adds Mr. Kappos.

Tobacco products and newspapers

“The first kiosks began as a small professional space, without fixed opening hours, with tobacco products as their main merchandise and subsequently items of primary and secondary necessity. (…) Newspapers in Greece at that time were truly an item of primary necessity. Due to the importance of news and the lack of other media, they were published at least three times a day. In most cases the news was unpleasant, which made it a necessary evil of everyday life,” wrote the newspaper EMPROS in 1956.

That year, according to the newspaper, more than 17,000 kiosks were operating in Greece. Of these, 5,500 were located in the greater Athens and Piraeus area, 1,500 in Thessaloniki, and the remaining 11,000 throughout Greece, with emphasis on the prefectures of Heraklion, Crete, and Achaia. Today, their actual number is unknown.

A milestone for the development of the Greek kiosk were the major military conflicts of the early 20th century. “After the Balkan Wars, a committee was established to care for destitute families of those who lost their lives in the war, as well as for war wounded. From then on, special legislation provided for the construction of kiosks in public and municipal squares, to be granted to war wounded so they could trade in the usual kiosk goods of the time. In September 1922, the Ministry of Welfare issued a law according to which existing kiosks, as well as those erected in the future, would be granted for exclusive use to the ‘Panhellenic Union of War Wounded 1912–1921,’” says Thanasīs Kappos.

In the following years, kiosks would have a uniform shape, color, and dimensions throughout Greece, with security shutters and refrigerators. They were placed on sidewalks, in squares, and in city and village groves, and gradually became a basic necessity of Greek society.

The exhibition is organized with the support of OPANDA, under the curation of Art Place Kyriakos Petalidis, and was inaugurated a few days ago with speeches by Elena Dakoula and Thanasīs Kappos.