Schools across Greece reopened this month and children filled classrooms with laughter, chatter, and the promise of a new year. But for many LGBTQI+ students, the return brings anxiety, fear, and a familiar question: “Will I be safe here?”

Earlier this summer, a 13-year-old boy in the Athens suburb of Fyli took his own life. Reports said he had endured relentless bullying, with classmates mocking his high-pitched voice and subjecting him to homophobic slurs and cruel pranks. His death, say educators, exposed a broader failure of Greek schools to protect vulnerable students.

“His story is not an isolated case. It reflects a systemic failure to protect students from LGBTQI-phobic bullying in Greek schools, says Elena Skarpidou, Education Division Coordinator at Rainbow School, a non-profit that campaigns for inclusive education. “This is the result of a system and a society that continues to look away in times of fluidity and complexity,” she tells TO BHMA International Edition.

What is Greece’s Rainbow School?

Founded in 2009 by teachers, social workers, and therapists, Rainbow School works to eliminate discrimination in Greek education. The NGO develops training programs for educators, publishes resources for classrooms, and advocates for laws that guarantee equal treatment. It also tries to break the silence around sexual orientation, identity, expression, and gender.

While Greece has passed progressive reforms in recent years, including the legalization of same-sex marriage which improved visibility for LGBTQ+ people in Greek society, the nation’s schools are lagging behind. “Laws change on paper, but not in classrooms,” says Skarpidou. “We want every LGBTQI+ student and teacher to feel safe, to learn and work without fear of bullying or stigma.”

“That also means training teachers to be able to discuss gender identity and sexual education, and to help children confront prejudice, stereotypes, and the stigmatization of diversity as well as sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.” For there to be real progress, Greece’s education system must keep pace with wider social shifts, she adds.

The ‘Invisible’ Problem

Drawing on 16 years of experience, Skarpidou, who is also a sexuality and relationships educator, describes LGBTQI-phobic bullying in Greece as both frequent and invisible.

The greatest difficulty, she explains, is that “instead of recognizing these as institutional problems that demand structural solutions, we downplay them and act as if they don’t exist. It’s always easier to blame the individual than to acknowledge the shortcomings of the educational framework.”

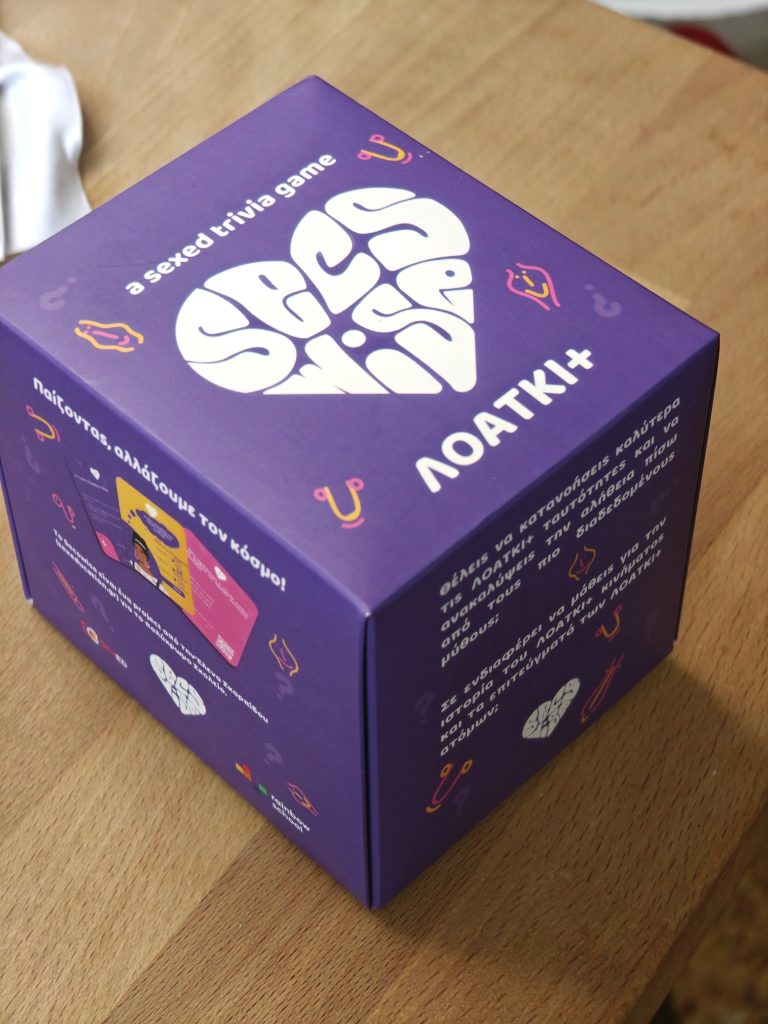

The purple box is a game created by the Rainbow School to promote understanding and acceptance of diversity. Photo: Rainbow School

Targeted Children Coping in Silence

Bullying often begins shockingly early. A recent Rainbow School study found that children often recall bullying linked to gender or sexual orientation from as early as the age of six, with incidents in primary school lasting longer and cutting deeper than those reported later in adolescence.

Bullying takes many forms: verbal abuse, demeaning tricks, scare tactics and physical violence. The lack of positive role models and accurate information compounds the stigma, leaving youngsters isolated. Yet incidents often go unreported, or are treated as isolated cases rather than systemic discrimination.

Socioeconomic background also plays a role. “In wealthier, more educated communities, acceptance tends to be higher,” Skarpidou observes. “But in poorer areas, LGBTQI+ children often face more hostility and have fewer allies.”

The consequences are severe. Skarpidou says that targeted children often withdraw into isolation. Some suppress their identities in a bid for conformity, others bury themselves in schoolwork, and some end up wrestling with depression and suicidal thoughts.

“This is why it is essential to design programs that nurture an inclusive environment from the very first grades,” she stresses. “Only then can we prevent future mental health problems.”

A girl holds up a sign with a clear message: ‘A school which embraces all children.’ Greece has a long way to go to ensure schools are safe for all. Photo: Rainbow School

Progress Blocked

On paper, Greece has taken steps toward equality. Same-sex marriage was legalized in 2023 and Law 5029 mandated new measures to prevent bullying. Provisions also included teacher training. Yet most of these remain unenforced.

“Not only has there been no substantial training,” Skarpidou notes, “the Ministry has not even circulated the guidelines for addressing bullying incidents that the law explicitly requires.”

Instead, the state has moved backwards. In 2023, the Greek Education Ministry withdrew all previously approved Rainbow School materials, along with other LGBTQI+ resources, from the Institute of Educational Policy platform. The reason given was a need for “re-evaluation,” but no explanation or timeline followed.

“There has been no response to our repeated appeals, nor to the interventions of the Children’s Ombudsman,” Skarpidou tells TO BHMA International Edition.

“As a result, teachers no longer have access to relevant resources for their classrooms and are reluctant to discuss such issues,” Skarpidou says. “The impact is particularly evident in rural areas, where bullying tends to be more frequent and more aggressive.”

Building Inclusive Classrooms

In its bid to foster inclusive classrooms and challenge entrenched stereotypes, Rainbow School develops teacher-training programs, runs seminars, produces educational material, conducts research, and collaborates with other organizations, all while pressing for the institutionalization of inclusion policies. But progress is limited, because participation remains voluntary.

“Educators who want to learn come to us on their own,” Skarpidou explains. “That’s not enough. Without the Ministry’s involvement, inclusion cannot be scaled up to the national level.”

To fill the gap, Rainbow School recently translated UNESCO’s International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education into Greek, hoping to encourage policymakers to adopt Inclusive-Integrated Sexuality Education (ISE) from preschool onwards—something most Western countries did decades ago.

“Education should start in preschool,” Skarpidou says. “Greece has signed international conventions that obligate us to provide inclusive, developmentally appropriate sexual education. Yet we still delay.”

Alongside the UNESCO guidance, Rainbow School’s website offers tools including practical guides on how to effectively handle bullying incidents, along with classroom worksheets, visual aids and materials designed to raise awareness.

But Skarpidou warns that resources alone are not enough. “Children, parents, and teachers must be able to report discrimination and schools must be prepared to respond.”

‘How Many More?’

Parents, teachers, and students can report incidents of discrimination through Rainbow School’s online platform, where cases are documented and followed up on.

Over the past year, LGBTQI+ students have contacted Rainbow School pleading for help, explains Skarpidou. Some report homophobic comments not only from classmates, but also from teachers. “This reality is deeply concerning. Too many children are stigmatized, without support from the adults who should be protecting them. They end up turning to us when their own community fails them.”

“How many more children must we mourn before we understand that schools must be safe spaces for everyone?”

For Skarpidou, inclusion is not an abstract goal, it is the measure of democracy. “An inclusive school recognizes every student, every teacher, and every family. It excludes no child. That is our responsibility- the responsibility of us all.”