AI-generated texts often embody an antihero and always start from the earliest point in a chronological order, both of which undermine their ability to behave like human stories. It is here that storytelling comes on-stream, with its incorporation into the Large Language Models (LLMs) being as essential as ever. Below, we probe into how these two properties of AI-generated texts can be rectified by the infusion of the storytelling craft.

The In Medias Res Beginnings in stories vs. The Ab Ovo (from the egg, i.e., from the beginning) Beginnings in LLM-generated texts

Storytelling counteracts the deficiencies of AI by offering in medias res beginnings that LLMs, by design, cannot. Great texts are great because, rather than beginning with exposition and scene-setting, they start in medias res, a technique that has its roots in Homer.

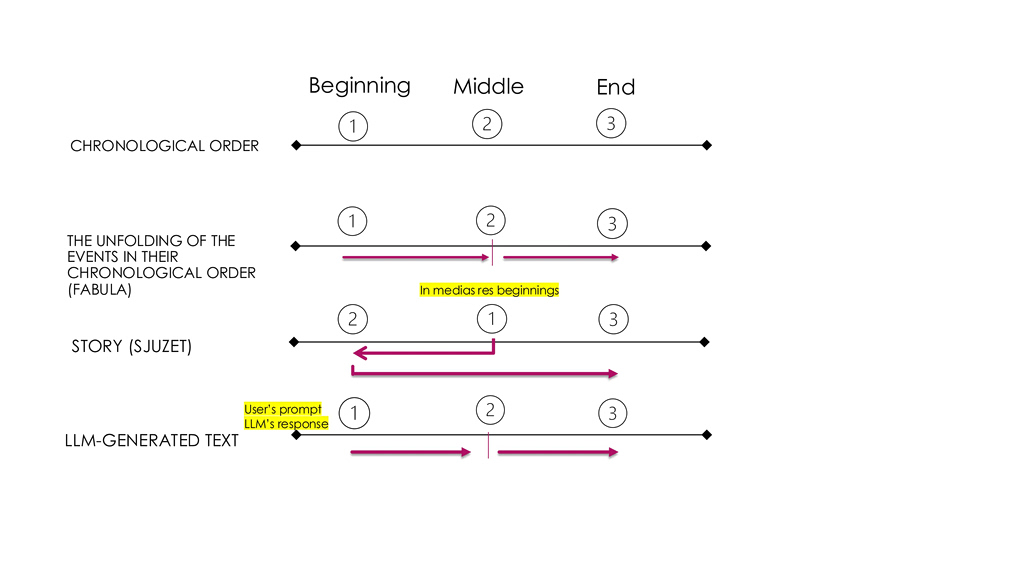

In place of a gavel-to-gavel coverage of what happened at the beginning (the exposition of the problem), where we are now (the middle of the story) and what will happen (an end provided either fully or only partially by the speaker and continued by the audience with downstream effects on the audience perception), great narrative texts opt to reverse the chronological sequence by starting from the middle. To put it differently, the start of the story never coincides with the chronologically earliest point in the portrayed events but with the moment of crisis and climax, a distinction in storytelling that has been called in the narratological lingo fabula versus sjuzet.

Take the Odyssey that starts with Odysseus marooned on Calypso’s Island of Ogygia, rather than the start of the Trojan War. Right there in the middle of the action, this narrative technique of reconstructed beginnings is crucial, as it paints a strong mental picture in the narrative perceiver’s- the audience’s- mind that will carry them through the rest of the narrative. What is notable here is that the opening in every text is the stage when the audience is most impressionable and receptive.

The opening in storytelling parallels the prompt engineering used in LLMs. Prompts in AI represent “your input into the AI system to obtain specific results. In other words, prompts are conversation starters: what and how you tell something to the AI for it to respond in a way that generates useful responses for you.” When the user writes a prompt, the LLM provides an answer starting off from that prompt, a process termed “prompt engineering.’ This means that the LLM does not put the audience in a specific frame of mind, because the LLM user has already set the frame of mind and cannot be overridden by the AI.

LLMs, like ChatGPT, take the user’s prompt and start from it. But that frame of mind is rarely right in the middle of the story, the place that causes curiosity and interest to soar, and LLMs by themselves cannot make the cognitive and storytelling leap needed for beginning in medias res. We need the thick of things at the beginning of the story: a narrative hook, some mystification, and a world turned on its head/subversive situation that puts us in an interesting frame of mind.

We need crisis- the ‘pregnant moment,’ the precipitating event, and the fight with the monster moment and conflict scene- but LLMs provide only taxis. This is one way in which embedding storytelling into the AI function can not only enhance it but also give rise to new features, properties, and capabilities for it as a result of a human-AI partnership.

Schematic showing of the translation by analogy between the stories that follow the chronological order in which the story events originally unraveled (fabula), the stories that follow a causal sequence rather than a chronological sequence starting from the middle of the action (sjuzet), and LLM-generated texts that always begin with the start that the user sets being unable to distort the order and start from the most interesting part of the middle of the action.

The antihero heroes of LLMs

LLM texts are usually perfect in that they are not beleaguered either physically or mentally. For thousands of years, humans, driven by the psychological need to know that someone has struggled behind every story, have been telling the same stories of individuals who plunge into a tumultuous journey, struggle, learn, grow, and become a different person. Joseph Campbell named this enduring universal language of humanity the “monomyth,” referring to the 17 typical stages that any story’s plot traverses and describing the profound human psychological tendency to recolonize the same narratives time and again. This dramatic structure that appeared at the dawn of storytelling, which coincides with the dawn of humanity, addresses a single theme: the “vicissitudes of human intentions,” as the cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner proclaimed. Every story deals with a human longing impeded by internal or external forces, and, as researchers from Boston University demonstrated, remarkably even very young squirmy children sit down longer to read stories about troubled heroes than about green meadows and sunny days. But an LLM doesn’t fear, want, yearn, wonder, care, hope, have aspirations, fall in and out of love, or is misty-eyed. Stories, as such, illuminate the human condition, and if AI misses the mark in incorporating elements reminiscent of the story heroes’ tribulations, psychological conflict, or situations in the firing line bustling with tension, it fails to be a good proxy for human thinking altogether.