In a remote mountainous area in northern Greece, a female brown bear and her cub spent weeks wandering around a village. Their presence was tolerated—until it wasn’t. The mother was shot dead. In the same broader region of Western Macedonia, two more bears were illegally killed within the span of a month, including a six-month-old cub.

“We can’t say there’s been an increase in killings compared to last year, but we are alarmed because they were all the result of bear interactions with humans. All three were shot,” Panos Stefanou, communications director at ARCTUROS, told To BHMA International Edition. “One was a six-month cub, so we can’t say it posed a threat. This is illegal—bears are protected.”

Encounters with brown bears—once nearly extinct in Greece—are becoming more frequent. The death of a hiker in northeast Greece in early June, believed to be the result of a bear encounter, has further stoked public anxiety. Yet data suggests these incidents are still extremely rare, and that most bears avoid humans.

Ioannis Mitsopoulos, current advisor to and former Director General of Greece’s Natural Environment and Climate Change Agency (NECCA), the body responsible for managing protected areas, told To BHMA International Edition: “I searched the literature for the last 30 years, and officially there has only been one bear attack by intention on humans. There is, however, a growing fear of bears among the people.”

The recent string of killings has shaken conservationists and leading NGOs like ARCTUROS, and brought renewed attention to a problem that has been simmering in Greece for over a decade: the increasing frequency of human-bear interactions.

The bears are not coming into villages to attack people. “They are coming in because they’re hungry, displaced, or in the case of some females, seeking safety from aggressive males who might kill their cubs,” says Stefanou.

An Ancient Species in a New World

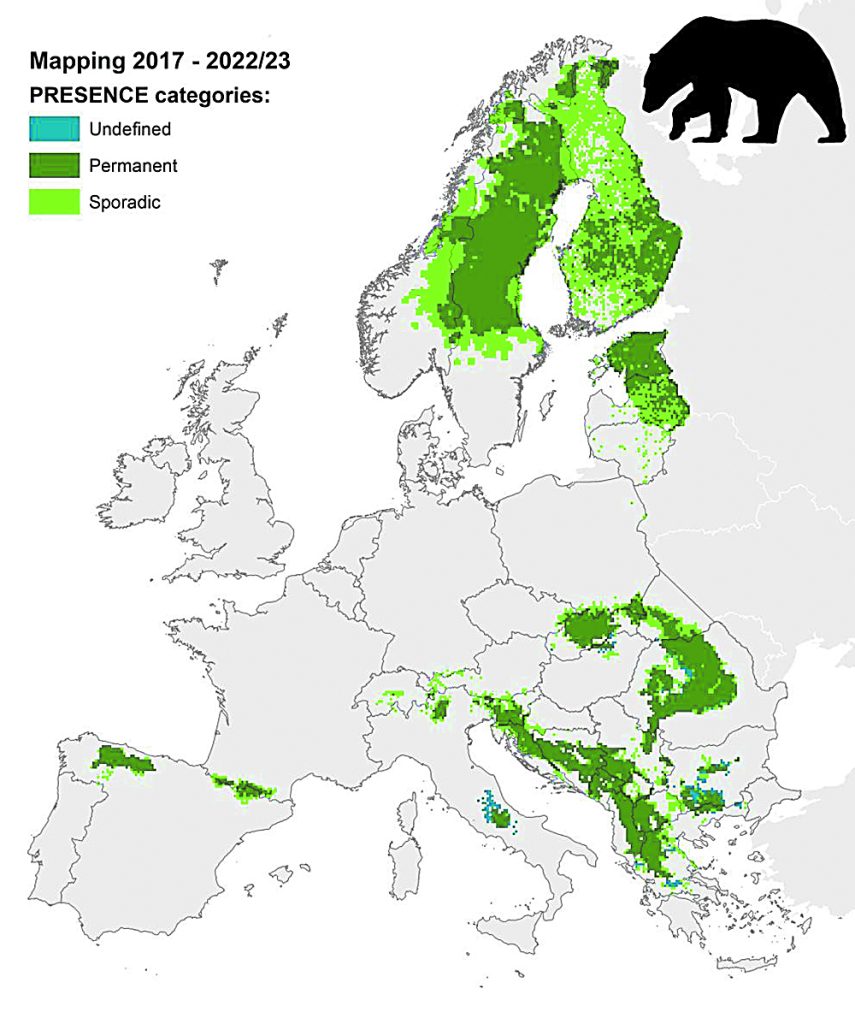

Greece’s brown bear (Ursus arctos) population has quietly rebounded in recent decades thanks to conservation efforts. ARCTUROS estimates there are now between 500 and 900 brown bears in the country, with their habitat covering around 50,000 square kilometers.

But this conservation success story collides with other trends—climate change, expanding development, and the fragmentation of habitat—that are pushing bears into closer contact with humans.

Changes in seasonal patterns are also affecting food availability. Bears follow their noses to trash bins, compost heaps, livestock feed, and fruit orchards—all easy meals, and all often found near human settlements.

The Greek countryside is often littered with waste from open and overflowing waste bins, offering easy pickings for hungry bears.

“This is not a Greek problem,” says Stefanou. “Wild animals everywhere are adapting to the human presence. It’s the new reality.” But while the bears may be adapting, ARCTUROS says Greece’s institutions are not.

“When there’s a burglary, you call the police. When there’s a bear in a village, people call the forestry service,” Stefanou explains. “But Greece’s forestry services are severely understaffed and under-resourced. They don’t have the tools or training to deal with wildlife.”

Instead, ARCTUROS says the responsibility often falls on NGOs like themselves or Callisto—which are not always state-funded or formally mandated and may not be reimbursed for their efforts.

Following the recent bear killings, ARCTUROS issued a 10-point intervention entitled “Living Together?” to clarify the situation and offer science-based recommendations. The document, which was authored by the organization’s scientific director, Dr. Alexandros Karamanlidis, warns that bear visits to inhabited areas have become “a near-mass phenomenon,” with bears of all ages even sighted within city limits.

But the heart of the problem, according to Stefanou, isn’t the growing presence of bears, it is “the lack of state capacity or interest in properly managing the problem, which is impacting both people and the bears themselves.”

Mitsopoulos agrees that the forestry service is understaffed, and gives insight into another layer of the problem. “There are some weaknesses in Greece’s system, because wildlife management involves numerous agencies. In Greece, horizontal cooperation with other authorities is difficult. So, while the funding is sufficient and the policies we follow are correct, we have coordination problems.”

Additionally, Mitsopoulos explains, “there is a lack of awareness within communities about how to coexist with wildlife. We have learned to live with earthquakes and severe wildfires. Now we must learn to live with wildlife.”

In Western Macedonia, local frustrations are rising. Some residents are demanding that the bears be sterilized or relocated. Others claim there are simply “too many.” In the absence of coordinated government action, a few have begun taking matters into their own hands—leading to illegal killings and growing tensions.

ARCTUROS disputes claims of overpopulation, however. “We have seen an increase in bears, but not on a scale to cause concern,” says Stefanou. “We don’t have a bear problem. We have a management and education problem.”

The organization highlights that, for more than 30 years, it has worked to reduce conflict between people and wildlife, donating over 1,000 livestock guardian dogs to Greek farmers, conducting environmental education programs, and intervening in more than 100 bear-related incidents. Still, they acknowledge that their efforts can only go so far without government support.

Meanwhile, Mitsopoulos explains that the NECCA has implemented a range of measures to mitigate human-bear conflicts with the help of EU funding. These include providing 2 million euros worth of electric fences to farmers, and establishing special dog patrol units for bear removal. Currently, two such units are operational in the Pindos Mountains of northwestern Greece, where they are used to deter bears from entering communities. Plans are underway to deploy three additional teams in northern Greece, near the Bulgarian border.

However, the approach is not without challenges. For instance, the patrol units cannot be used to deter mother bears with cubs—precisely the type of situation involved in a recent bear killing.

Δείτε αυτή τη δημοσίευση στο Instagram.

Europe’s Bear Dilemma: Controls vs. Coexistence

Brown bears are strictly protected under both Greek and EU law. According to the EU Habitats Directive, they may not be deliberately killed, disturbed, or removed, except under narrowly-defined emergency situations or official legal derogations. Greece complies with this mandate fully: no hunting season, no quotas, no official culls.

Yet across Europe, hundreds of the continent’s 20,000 plus bears are legally killed each year under approved exemptions. Sweden, for example, issued hunting permits for around 640 bears in 2024—which equate to nearly 20% of an estimated population of 2,400–3,300. Romania, which is home to Europe’s largest bear population, has doubled its annual quota to 481 following a fatal incident. Slovenia and Croatia both reported annual population removals of 9-18% during the 2000s.

Credit: LCIE

These countries argue that lethal controls are necessary to protect livestock and prevent dangerous human-wildlife conflict. But critics warn that such large quotas may breach the spirit—if not the letter—of EU law.

Greece, by contrast, has taken the high road: coexistence through prevention, education, and emergency response. However, this approach is increasingly under strain. In his recent statement, Karamanlidis offers a sobering assessment in answer to the question: Can humans and bears live together? His answer: “Both yes and no. Yes, in the sense that the brown bear population is recovering and its habitat use is changing. The Greek countryside is not what it was 20 years ago, and neither are the bears. But from habitat shift to a bear in someone’s yard is a long and potentially dangerous road. On that point, the answer must be NO.”

What is needed now, say conservationists, is not panic but planning.

Overflowing trash bins in Greece are easy-pickings for bears. Athens New Agency/ Panagiotis Saitas.

ARCTUROS is calling for urgent action from central government: support for trained wildlife response teams, improved waste management in bear-prone areas, local education campaigns, and the integration of wildlife planning into rural development strategies.

In response to mounting concerns, the Greek government last week announced a new wildlife management policy allowing for the removal of so-called “problematic bears.” ARCTUROS quickly condemned the measure as “illegal.”

Mitsopoulos disagrees with the characterization of the measure as “illegal,” but cautions against oversimplifying the process. “It is not illegal to move or reallocate a bear, but you cannot move entire populations,” he explains. “In any case, bear removal is very difficult to implement in Greece, because the country is small and the habitats where bears can live are specific and limited. This isn’t the U.S. or Canada. Also, with bear removal you’re just transferring the problem from one area to another. Instead, we must apply measures that are relevant to the needs of local communities.”

Proven preventative measures from other bear-inhabited regions of the world include bear-proof food storage bins and secure waste bins./ Photo by Cheryl Novak.

The issue is straightforward. Habitats are degraded and land and traditional activities such as stock raising have been abandoned, so bears are entering villages and wildland-urban interface areas looking for food—usually in trash cans,” Mitsopoulos explains.

He highlights a deeper, chronic issue that exacerbates the situation: “The way we manage our trash is a big problem. This is one of the most important steps we should take to minimize negative human-bear encounters.” It is true that the Greek countryside is often littered with waste from open and overflowing waste bins, offering easy pickings for hungry bears. Tackling this issue would not only help reduce bear-human encounters, it would also improve communities’ overall environmental health.

Fortunately, proven solutions from other bear-inhabited regions, such as bear-proof bins and secure waste containers, are readily available. However, their effectiveness relies on more than infrastructure alone; they also require public education and, perhaps most importantly, a collective will to change.

Write to Cheryl Novak at cnovak@tovima.com