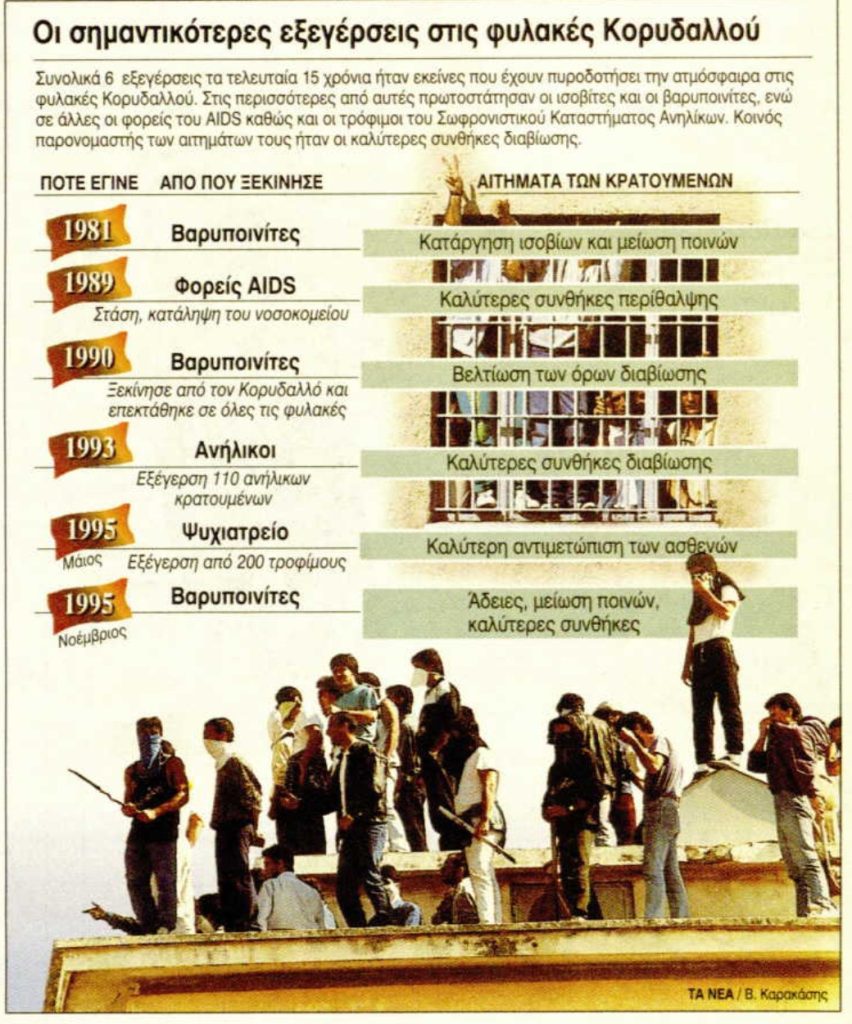

Today marks 30 years since 14 November 1995, the day the Korydallos Prison uprising erupted—an event widely regarded as the largest and most violent revolt in the history of Greek prisons.

The uprising left behind extensive destruction, hostage-taking of correctional staff, dozens of injuries, and four inmate deaths.

Three prisoners died from massive overdoses of narcotic pills.

The fourth, 27-year-old inmate Dimitris Karamoutis, was brutally murdered by fellow prisoners in one of the most chilling crimes ever recorded inside a Greek correctional facility.

Newspaper archives from TA NEA and TO VIMA at the time describe scenes of “unprecedented violence and savagery.”

One inmate told reporters that prisoners had “danced around the body of a man they had hanged and burned”—a chilling snapshot of the lawlessness that engulfed the prison complex.

A Hostage’s Testimony: “They threw me to the ground and ran past”

One of the correctional officers held hostage, chief warden Kostas Kostopoulos, recounted the events to TA NEA and journalist Dionysis Nasopoulos.

On Tuesday afternoon, as Kostopoulos began his shift in Wings B and C, he saw a group of 50–60 prisoners—mostly Albanian nationals—rush toward him, knock him down, and storm out into the yard.

He describes waking up dazed, hearing the sounds of cells being smashed open.

Not knowing whether escapes were underway or how bad things might get, he attempted to hide in a cell. A prisoner, surprisingly, reassured him: “You’re fine now.”

But within minutes, the prisoners of Wing B also flooded into the corridor. Some ignored him; others shouted, “Stay where you are.”

He remained locked inside the cell for two hours, unsure whether anyone outside was still alive.

“The uprising had spread everywhere”

By nightfall, the revolt had turned full-scale.

At 10 p.m., prisoners escorted him out of the cell and took him to Wing A, where another officer, Panagiotis Kyriakoulis, was hiding. Both were then moved back to Wing C.

There, in a second-floor cell, they found six other hostages, anxiously watching television coverage of the uprising.

Remarkably, the captors did not harm them, assigning their own “guard team” to watch over the hostages.

Meanwhile, TV stations had gone into live broadcast mode from outside the prison. Prosecutors and officials rushed to the scene, while inmates inside distributed coffee, orangeade and cigarettes to other prisoners—an eerie mix of chaos and attempted order.

The eight hostages whispered among themselves, aware they could do nothing.

At least, no staff member had yet been injured.

They heard reports that negotiations were beginning. The hostages pleaded with the inmates:

“Please—don’t harm staff or prisoners, and we will help prevent an armed intervention.”

But violence had already begun inside:

Several prisoners were stabbed, some because they opposed the uprising, others because, as Kostopoulos said, “some took the opportunity to settle old scores.”

The Most Terrifying Hours: 1 a.m. – 3 a.m.

Between 1 and 3 in the morning, the situation reached its peak.

Tear gas rained outside. Gunshots echoed.

Prisoners grew enraged.

Kostopoulos feared “anything could happen—there was no way an intervention would be bloodless.”

The hostages were moved to another cell and permitted to phone their families, unsure whether they would survive the night.

At dawn, despite the collapse of negotiations, the rioters agreed to release two hostages as a gesture of “goodwill.”

First to be freed was the psychiatrist, Dr. Alekos Filippakis.

Twenty-five minutes later, Kostas Kostopoulos walked out through the main gate—unnoticed by the crowds outside—after passing through the administration office.

He publicly thanked the inmates for not harming him.

But he also made a plea: release the remaining hostages unharmed.

Reflecting on the cause of the uprising, he said:

“At first I thought it was a normal revolt. If some tried to escape, that’s natural. Everyone knows we don’t have enough staff. Korydallos was a sinking ship.”

The Psychiatrist: “I never imagined being caught in this”

Dr. Alekos Filippakis, the first hostage released, told TA NEA that he had been filling out medical forms in the prison infirmary when the riot began.

He had been visiting the prison for eight months as an external psychiatrist, not part of the permanent staff.

“I never imagined I would be part of something so serious,” he said.

“They didn’t harm me, but the anxiety was real—for me and for my family. None of us knew how it would end.”

How the Uprising Ended

Late on 15 November 1995, the remaining six hostages were released.

The uprising ended shortly after midnight when Justice Ministry officials assured prisoners that their demands would be considered.

The prison employees—held for nearly 30 hours—left exhausted but unharmed, refusing to comment publicly.

The end came abruptly, even as injured inmates were still being transported to hospitals.

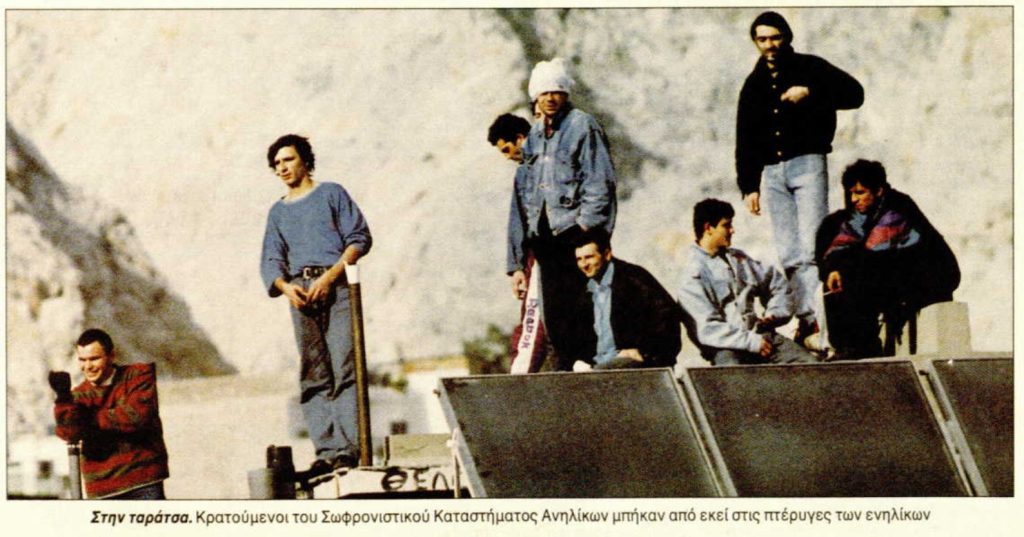

Just after midnight, a group of prisoner representatives demanded live access for TV crews.

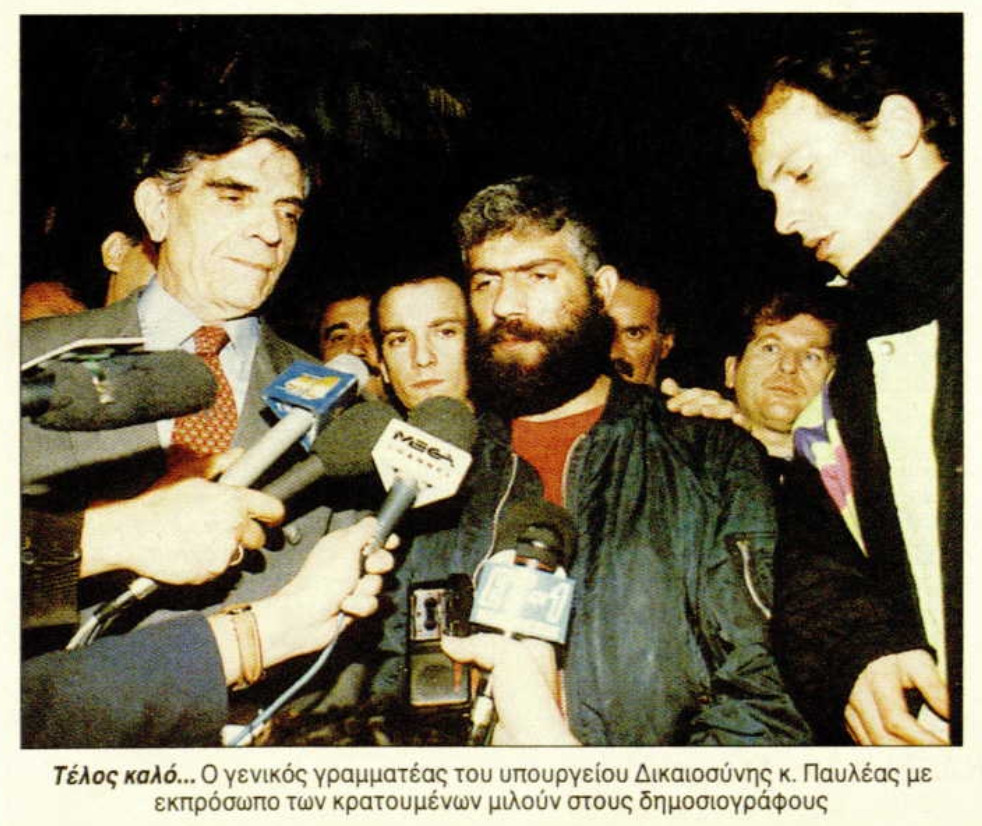

In the courtyard, three lifers waited to speak to reporters in the presence of the Justice Ministry’s secretary general S. Pavleas, two PASOK MPs, and the prison director.

The representatives—Pantazis and Seremetis among them—announced the release of the hostages and declared the occupation over.

Their primary demands:

- improvement of living conditions,

- better medical care,

- faster procedures for release after serving one-quarter of a sentence,

- enforcement of laws governing pre-trial detention.

Pavleas assured them these demands would be accepted.

Prisoners responded that they trusted the ministry.

Asked how the revolt began, they blamed an attempted escape by a group of foreign inmates.

As for the injured, one representative said tersely:

“This is a prison, not a college.”

They did not deny frequent clashes between Greek and foreign prisoners.

The Monstrous Murder of Dimitris Karamoutis

The murder case of 27-year-old inmate Dimitris Karamoutis—killed during the uprising—went to trial in January 1998.

As TA NEA reported, Karamoutis was stabbed 23 times in the heart and lungs, then hanged and burned to destroy evidence.

Five men were identified: two primary attackers and three accomplices.

All were considered central figures in the uprising, which claimed four lives.

Only three stood trial.

One had been released due to a procedural failure to issue a warrant;

another escaped the previous summer and had not been found.

Four additional inmates were also tried as instigators of the revolt and for the hostage-taking of eight staff members.

The prosecutor’s findings, prepared by Deputy Appeals Prosecutor Antonis Mytis, described a murder of exceptional brutality.

“Wrong victim”

Chief warden Giorgos Papatheofilou, who came on duty after the hostage crisis, testified that the killers may have mistaken Karamoutis for another inmate—Alexakis—whom they believed was a police informant.

He did not rule out another motive: intimidation.

“They needed to show they were in control,” he said.

Intimidation in Court: “I stabbed you then—why fear saying it now?”

The trial revealed the fearsome internal laws of the prison world.

One eyewitness, who had seen the murder, begged for state protection.

Judges tried to reassure him, but chaos unfolded when the main defendant turned to him and taunted:

“I stabbed you back then. Why are you afraid to say it?”

The courtroom froze.

The witness fled.

The key witness that day, Stavros Lambropoulos, later told TA NEA he feared not the killers themselves, but their “unknown friends” who might attack him later if he testified.

When Prosecutor Evgenia Papageorgiou finally secured assurances of protection, Lambropoulos named Nikos Pantazis and Konstantinos Fotiou as the killers.

He also testified he saw brothers Panagiotis and Christos Stantzos outside Karamoutis’ cell as they set the body on fire.

From his own cell, injured, he recognized Pantazis by voice and saw the Stantzos brothers through the door window.

He also confirmed a previous statement from inmate Vasilis Vorilas: there was an order to kill him because he had informed on drug activity in another prison. He implied Karamoutis was killed by mistake.

But the testimony collapsed when Pantazis’ defense attorney used the word “snitch” in the courtroom.

Furious, Lambropoulos stormed out, vowing to file charges.

The Verdict

The court sentenced the defendants to:

- life imprisonment, plus

- 18.5 years,

for:

- murder,

- attempted murder,

- kidnapping of correctional staff,

- aggravated destruction of property,

- inciting a riot.