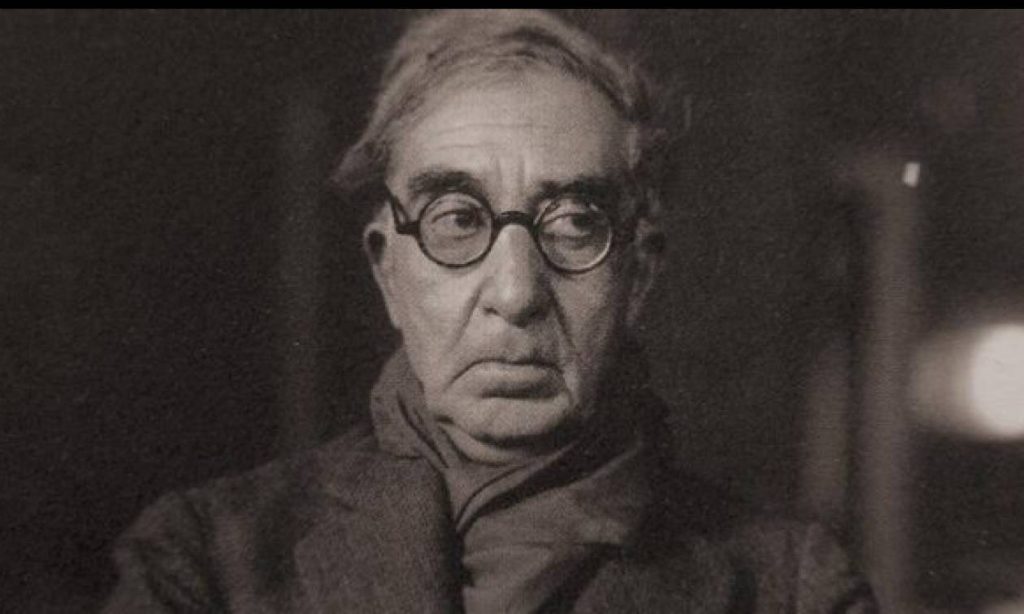

The Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933) never published a book, yet today no anthology of world poetry can afford to neglect him. He was great poet of history, psychology and erotic yearning. His meticulous verses of beauty and folly, delusion and disillusioned wryness, were forged from his reading and his private life as a homosexual—experiences he rendered with a jaded power. His friend E.M. Forster once described him as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.”

Cavafy, who lived most of his life in Alexandria, Egypt, remains the most influential of all modern Greek poets. Yet it is a miracle we know his work at all. He self-published individual poems in broadsides distributed to friends and family, occasionally binding small collections in limited editions. The first Greek edition of his poems appeared in 1935, two years after Cavafy’s death. His work was composed exclusively in Greek, a language he spoke with an English accent (he was a subject of both the Ottoman and British empires). He was not a nationalist, but a poet of singular vision.

It was a vision with global appeal. In the 1920s, T.S. Eliot published early translations of Cavafy in his literary magazine the Criterion, which deeply influenced younger writers such as W.H. Auden. Finally, in 1951, the Hogarth Press would bring out a collected edition of Cavafy’s poems rendered in English. The canon grew through new editions and translations, until Cavafy became, as Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys assert in “Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography,” a “world poet.” His most beloved poem, “Ithaca” (1911), which revises the voyage of Odysseus as a parable of life’s journey, can be found everywhere on the internet:

Here I give the unfussy translation of Messrs. Jusdanis and Jeffreys, who are both seasoned scholars of Cavafy’s work. Few who render Cavafy into English convey anything like his sound, which Daniel Mendelsohn, who translated a two-volume collection of Cavafy’s complete poems, has called “deeply, hauntingly rhythmical, sensually assonant when not rhyming.” Usually in English the poems have a simple, flattened manner, so what comes across is the ironic drama of “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1904), the mystery of “One of Their Gods” ( ca. 1917), or the shattering religious transformation of “Myris: Alexandria of 340 A.D.” (1929). This last poem, spoken by a pagan youth remembering his dead friend, concludes (in the translation of Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard):

What’s often missing is the passion and astringency of the originals. Cavafy deliberately mixed demotic and “purist” Greek, rather like a modern English poet employing archaisms that distance us from the poems. Though he’s famous as a pioneer of free verse, nearly half of Cavafy’s poems use rhyme, often ingeniously. “Walls” (1897), an important early poem, finds homophones for rhymes: the Greek word for walls, teíchi , sounds exactly like the word for fate or luck, týchi , making us feel that walls have conspired to trap the speaker inside both a city and his own mind . Perhaps only a few translators, such as Seamus Heaney and A.E. Stallings, have managed to convey that texture of intellect and sensuality.

Messrs. Jusdanis and Jeffreys have produced an important biography of an indispensable poet—the first to appear in English in nearly 50 years. They note the care with which Cavafy archived the materials of his life, “from his entry card to the Alexandria stock exchange, to theater tickets, drafts of letters, lists of things to do,” along with versions of his poems. Such diligence, the biographers write, suggests “he had expected someone to write his life story.” Still, Cavafy remains at a distance, withholding self-revelation—partly because most of his letters were destroyed, either by himself or by friends and family. Homosexuality was illegal in his lifetime, and he was excruciatingly aware of the shame, imprisonment and impoverishment meted out to his contemporary Oscar Wilde.

Perhaps no biography could capture so elusive a man. The new book is thematic rather than linear, a sequence of biographical essays that doesn’t build dramatic power so much as it sends shafts of light into its subject’s intellect. The authors address problems faced by any Cavafy biographer. After his death, “what began to circulate were bits and pieces of a fragmented portrait as people tried to supply the missing parts from memory.” An early chapter treats Cavafy’s youth among prosperous Greeks in Alexandria, and how the family fell on hard times when his father died. From age 9 to 14 he lived with his family in England. They returned to Egypt in 1877; not until Chapter 5 do we get a portrait of the 1882 revolt of Arab Egyptian nationalists and the British bombardment of Alexandria that would cause the Cavafys to flee again, this time to Istanbul, where Constantine would remain until he was 22 years old.

“Ultimately,” his biographers write, “Constantine was most happy, free, and true to himself in the Alexandria of his creation.” In his late 20s he went to work in the office of the Irrigation Service, a clerkship that lasted 30 years. The schedule was undemanding and the job afforded him time for poetry, as well as the secret sexual liaisons he pursued in the city. One of these is recounted in a sly poem called “Their Beginning” (1921) less about the start of an affair than about the “strong lines” the poet will write many years later.

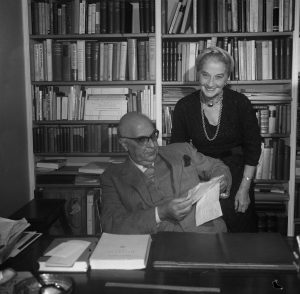

Evenings in his apartment at 10 Rue Lepsius often became a literary salon where Cavafy built and managed his reputation, “one reader at a time.” A complicated friend, Timos Malanos, “hailed Constantine’s conversational skills,” calling him “a miracle-worker of words” (the homophobic Malanos would eventually become, the biographers note, a “harsh and unforgiving critic” of the poet). Such testimony makes me regret that no recording of the poet’s voice exists.

I wish his new biographers had said more about Cavafy as a poet of psychological skepticism, who found his material in our habitual errors and our mortality, but we owe them a debt for assembling this mosaic of a life and sending us back to the poems where he really resides—at a slight angle to the universe.