Paul Homchick bought his first fountain pen three decades ago. He was working as an engineering consultant and wanted to seem trustworthy as he took notes.

Since retiring, the 76-year-old has been more interested in exploring different types of nibs, the metal tip of a fountain pen, than impressing clients. To save money, he decided to give Chinese brands a shot.

Now nearly half of Homchick’s 59 fountain pens are Chinese-made. That includes a $30 Chinese version of a Montblanc pen that costs about $750 today.

“In writing,” he says, “there’s not that much difference.”

Some of his fellow enthusiasts would like a word.

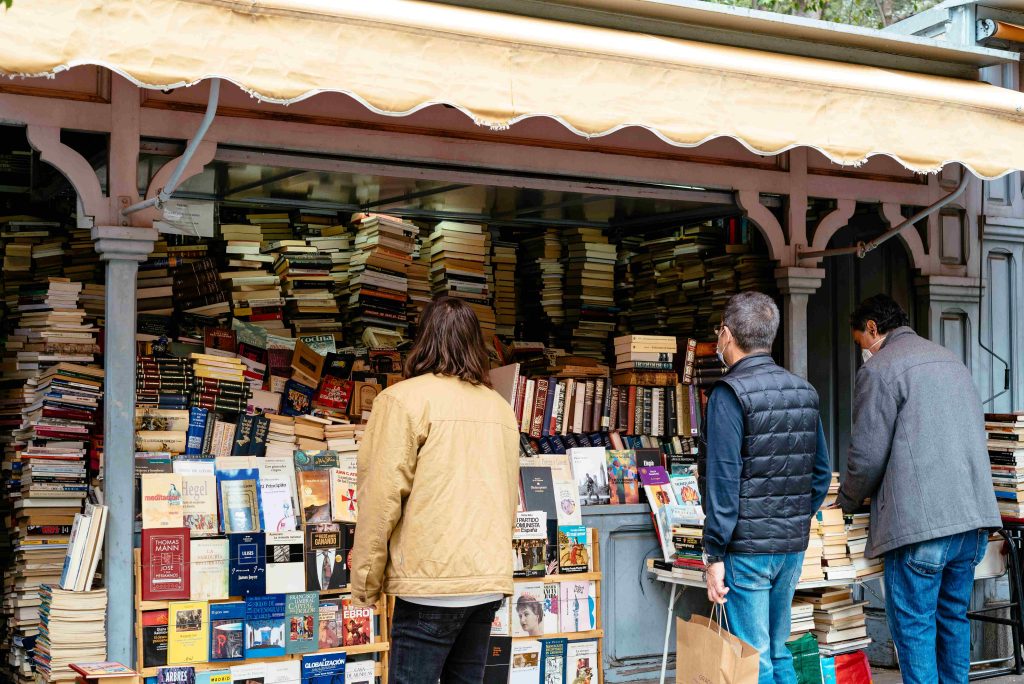

Cheap replicas are flooding the market for the old-timey pens, rankling fans of a product long known for steep prices and a user base dominated by royalty, politicians and wealthy elites. The products are attracting new waves of buyers and have made the writing utensils more popular than ever. The Reddit group dedicated to fountain pens has doubled over the past five years to about 368,000 users.

That growth is also striking a nerve.

L. Bruce Jones, of Idaho, refuses to add a Chinese copy to his collection spanning roughly 450 pens from Switzerland, Italy and elsewhere—including limited-edition Montblancs that run up to $20,000 each.

Jones, 69, says that back when he was running a submarine company that built the world’s deepest-diving submersible, a rival company in China tried to poach his employees and hack into company servers. He’s not about to support the country in its pursuit of Big Fountain Pen.

“I just find it reprehensible,” he says.

Montblanc’s snowcap logo on the Meisterstück Classique line fountain pen. Janelle Jones for WSJ

China has muscled into industries from fine wines to designer handbags to luxury watches. Its pens—which look like the real thing but often sell for just a few bucks apiece—can force consumers to wonder what exactly they’re getting from the entrenched brands, said Willy Shih, a professor at Harvard Business School specializing in manufacturing and supply chains.

“Are you buying a writing instrument or a symbol of exclusivity?” Prof. Shih says. “It depends what job you’re hiring that product for.”

American inventor Louis E. Waterman is credited for developing and patenting the first modern fountain pen in 1884—one that could store ink inside and eliminate the need for a separate ink pot. In the late 1920s, the Sheaffer Pen Company introduced a lever-filling mechanism and a tapered shape that influenced the cigar-shaped fountain pens that came after.

As convenience gained importance, fountain pens became more of a collectors’ item. The most elusive offerings—often called “grail” pens—may have handcrafted nibs or are vintage or limited editions.

Chinese rivals first appeared on e-commerce platforms about a decade ago. They’ve become far more widespread in recent years due to their rising quality and low prices.

This is a headache for old-guard penmakers. Michael Gutberlet, CEO of Kaweco Pen Company, a German penmaker founded in 1883, tells his industry peers that dirt-cheap Chinese copies are as big of a threat as the decline of handwriting.

Gutberlet recalled friends alerting him to an uptick in Chinese imitations of Kaweco’s pocket-size “Sport” pens for a 10th of the price. At first, he tried asking the Chinese companies nicely to stop. He emailed, then sent letters.

He even confronted a Chinese vendor in-person at an industry trade show. None of it worked. Finally, Gutberlet trademarked the pens’ names and asked major e-commerce platforms to remove them. For a while the rip-offs went away. But after several months, they re-emerged—but with new names.

“They have so many young designers,” Gutberlet says, “They can make their own thing.”

Pierre Miller, an independent penmaker in Chicago, calls the Chinese-made pens “obviously inspired.” His own lineup of pens start at $95 and max out at roughly $350.

Miller says the rise of Chinese entrants—knockoffs and original designs—can broaden the fountain-pen community. Their affordability lowers the barrier to entry for a new generation of fans.

“The enthusiasm is no less palpable,” Miller says.

Irv Tepper, an artist in New York City, has a collection of about 200 fountain pens. That includes a Montblanc and a limited-edition Conway Stuart that is a replica of a fountain pen from one of the “Indiana Jones” movies. But the 78-year-old’s grail pen is a Pelikan M1000.

Limited-edition Montblanc pens can run up to $20,000 each. Janelle Jones for WSJ.

Writing with the German-made pen, Tepper says, is “almost like riding a wild horse” because it’s a larger pen with an extremely smooth nib.

Tepper will buy Chinese look-alikes too as long as they’re not counterfeits. “All pens pretty much look like themselves,” he says.

The cheaper pens are better for everyday use, and he likes gifting them to friends, hoping they get hooked on fountain pens. “I try to sucker other people into the game so I’m not alone in my addiction,” he says.

Tepper maintains a separate binder of colorful Jinhao pens, costing about $12 each, but his appreciation for the Chinese pens has limits.

“If the house burned down, would I grab one?” he says, “No, I’d probably grab a Pelikan.”

Write to Timothy W. Martin at Timothy.Martin@wsj.com