KYIV, Ukraine—Ukraine’s power grid has weathered three winters of Russian bombardment during which engineers patched up substations under missile and drone fire and civilians spent days in the cold and dark as Moscow attempted to sap their resolve.

Now, heading into their fourth winter of war, the country’s energy suppliers are banking on a network of massive, U.S.-designed batteries held at top-secret locations to help keep the lights on.

At one such outdoor site this fall, rows of 8-foot-high white battery blocks emitted a constant high-pitched hum.

“The best sound in the world,” because it means they’re working, said Vadym Utkin, an adviser on energy storage to DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private-energy supplier, which spearheaded the project.

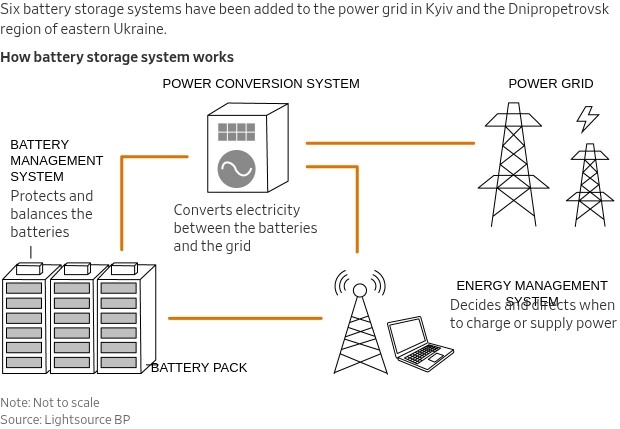

The battery parks, with a combined total capacity of 200 megawatts, can supply around two hours of energy for roughly 600,000 homes, equivalent to powering a city about the size of Washington, D.C. Most crucially, under bombardment the power cells buy engineers time to restore service and prevent a blackout.

The battery parks are designed to help plug holes in and regulate Ukraine’s energy supply, offering an alternative source of power even when the grid comes under attack.

The $140 million battery program, completed in August, is crucial for Ukraine, which has raced to modernize and decentralize its electricity grid in part to help it withstand Russian barrages.

To avoid making the batteries a target, Ukrainians are tight-lipped about their specific location and details of the measures in place to protect them from Russian attack, which include strategically placed air defenses.

The six sites across Kyiv and the Dnipropetrovsk region connect to the power grid and deliver power if another source, such as a thermal-power plant, goes offline, helping to avoid the rolling blackouts Ukrainians have experienced for years.

“We have lost more than half of our generating capacity due to destruction by rockets, Shaheds, and so on,” said Olha Buslavets, Ukraine’s former energy minister, referring to the type of attack drone favored by the Kremlin.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, all of Ukraine’s thermal-power plants have come under attack. Although some power stations are back online, others are beyond repair.

Before the war, Ukraine obtained most of its energy from its nuclear-power facilities, which Russia has since targeted. Ukraine’s largest nuclear-power plant is no longer providing the country with energy after being occupied by Moscow’s forces at the start of the conflict. Nuclear power now makes up about half of Ukraine’s energy mix.

Russia’s campaign against Ukraine’s energy infrastructure is designed to punish civilians by depriving them of heat and electricity over the cold winter months, in the hope that Kyiv will bend to Moscow’s will. The strategy, which has seen Moscow bomb substations, coal mines and gas sites, hasn’t worked so far. Last winter, energy workers largely maintained the power supply even as missiles and drones rained down on them .

But since then, Russia has ramped up its production of attack drones, allowing it to overwhelm Ukraine’s air defenses by sending hundreds of the unmanned aerial vehicles in a single attack, an approach likely to make this winter even more perilous for Ukraine.

In U.S.-brokered peace talks earlier this year, Russian and Ukrainian negotiators discussed a cease-fire on each other’s energy infrastructure. Over the following months, attacks on power plants lessened, but as the winter approaches both sides are increasing such assaults. Ukraine has taken out at least 15% of Russia’s oil-refining capacity in response to the targeting of its energy sites, and 77,000 people were without power after an attack in Russia’s Belgorod region last week, according to Russian state media.

“If we don’t have any agreements, some kind of cease-fire, talks and so on, then these attacks with the coming cold will be more targeted, more practical, and, of course, they will bring nothing good,” Buslavets, the former energy minister, said of strikes by Russia.

To combat aerial assaults, Ukraine has persistently asked for more air-defense capabilities from its allies in the West and has particularly sought the Patriot, the American-made system capable of intercepting ballistic missiles. President Trump has promised the delivery of more systems and Ukraine is set to receive two additional systems from Germany by the end of the year, but says it needs more to fully protect its cities and infrastructure.

Building out alternative sources of energy, such as wind and solar, has also been a matter of defense for Ukraine. Renewables won’t fully replace nuclear or coal, but their presence injects diversity into the energy mix. They also operate independently, which is an asset in a war zone, where if one wind turbine is hit the rest can keep turning, compared with a thermal power station that comes to a complete halt if it is struck.

Batteries are now playing their part in renewables too, helping regulate energy generated from all sorts of sources to make sure that electricity flows even when the sun doesn’t shine or when turbines stand still.

“There’s always fluctuation, there’s always mess in the system, and somebody needs to clear this mess,” said Utkin, of DTEK. “These machines actually clear this mess very, very effectively.”

Much of what makes batteries an attractive option for Ukraine is their modularity. Each block can be taken offline and replaced with no impact to other cells. Were one of them hit, Utkin said, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. “I would be crying and just cursing, but honestly, to replace one cube is not so difficult,” he said.

Although the new network is the largest series of battery parks in Ukraine, it isn’t the first. In 2021, Utkin oversaw the construction of another such park in Enerhodar, a city in Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia region that Russia occupied the following year. A few hours before Russian forces entered the region, Utkin wiped the software from the batteries, turning them into “expensive bricks” that are now essentially useless.

Minimal equipment is required to replace each cell in the new network, and all of them have fire-safety features that “in the context of Ukraine become more important,” said Julian Nebreda, the CEO of Fluence , the American company that supplied the batteries.

Despite Russia’s bombardment of the electricity grid and the risk to the batteries themselves, Nebreda said his company didn’t hesitate to sign up to be part of the project, which was financed by DTEK and loans from a consortium of Ukrainian banks.

“Everybody understood the importance of getting this done,” he added.