How did The Great Nothing come about? What was the initial idea, and when did it begin to take shape?

The first thoughts go back to 2019, when I was shaping my previous work, Atitlon. I was keeping notes alongside that more mature piece, and when we began experimenting and rehearsing about 18 months ago, it was precisely because I intended for a break—and a rupture—with what came before to occur simultaneously through a new work.

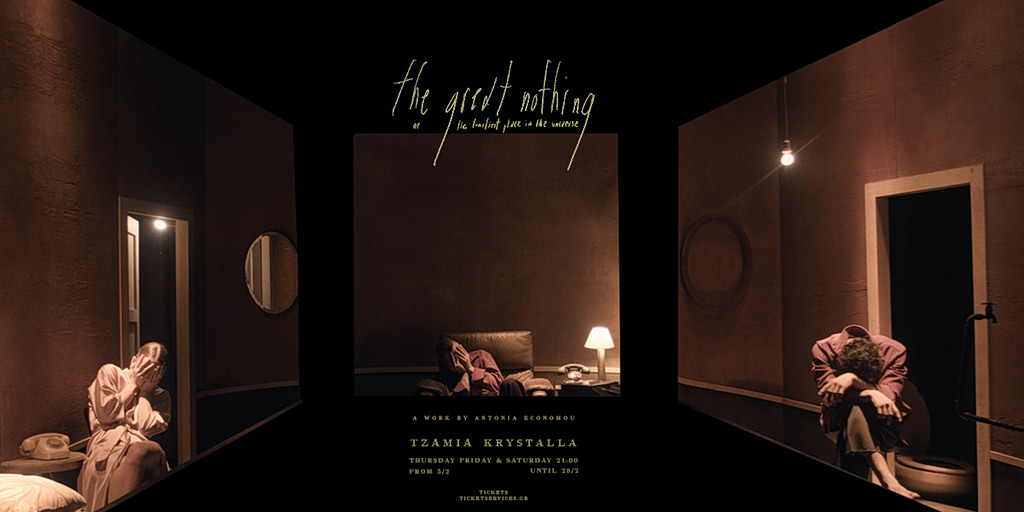

I invited my collaborators into our space [Tzamia Krystalla], and we devoted time to giving meaning to this confrontation, through the counterpoint of light and darkness. In the meantime, over the summer, I read A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, which discusses black holes, where the distortion of time—expansion and contraction—is a defining feature. In it, he refers to the Boötes Void, or the Great Nothing: a region of the universe where the density of galaxies is far below average. If you were theoretically to stand at its center, you would be at the most isolated point possible. That parallel is what we see on stage.

Blackness, the movement of a single body, stillness, and the method of the jump cut. That’s why the visual language recalls cinema—I believe the viewer’s gaze will move accordingly. We play with that rhythm, and when people ask me what kind of film we are, I say: an erotic noir horror.

Photo by Christos Andrianopoulos.

Speaking of horror and distance, we’ve already seen some of the images released publicly. There seems to be a strong focus on intense upper-body movement. Do you draw from everyday life to shape this kind of movement code?

Absolutely. I’m obsessed with hands—I love using them. I constantly observe people in states of despair. We studied Rodin’s sculptures, which operate within the same logic of distortion. We also studied Francis Bacon kinetically, precisely asking how the poses in his works—so often rooted in everyday gestures—might evolve under conditions of deformation. I like to start from everyday triggers. I believe that from a state of stillness, like in a photograph, dozens of movements unfold that can serve as points of departure for me.

What continuities and what ruptures do you see in relation to your previous works?

Atitlon, despite the mourning it carried toward its end, was focused more on love than on separation and loss—concepts that The Great Nothing engages with directly. In the current work, it’s as if the ground disappears beneath your feet for an hour and ten minutes. Structurally, it’s a more individual, more existential piece. Otherwise, I’ve carried elements over from Atitlon into this work, most notably the feminine presence. I’m also accompanied by elements from my short films—such as the radio—which functions as a means of communication for my characters, who are, by general admission, lost.

Short Bio

Antonia Economou is a dancer and choreographer. Her academic engagement with art history, combined with her movement practice, plays a decisive role in her work, fueling an ongoing dialogue between cinema, visual art, and stage creation through image-based dramaturgy. She explores themes such as decay, erosion, and the complexity of the human mind, illuminating those areas where the boundaries between the real and the imagined begin to blur.

More information on the show can be found here.