Meeting chef Alsi Sinanaï at Tribeca in Thessaloniki feels like stepping into a world where cooking is not merely a job, but a way of thinking—and a daily search for balance between fire, memory and human connection. In the restaurant’s open kitchen, where movement has both rhythm and silence, he works with the confidence of someone shaped by years of testing, travel and rethinking his relationship with food.

At his side is David, his young son. Not a passive observer, but—by Sinanaï’s own presence online and in the kitchen—a small companion in a story that goes beyond professional identity and into the heart of family.

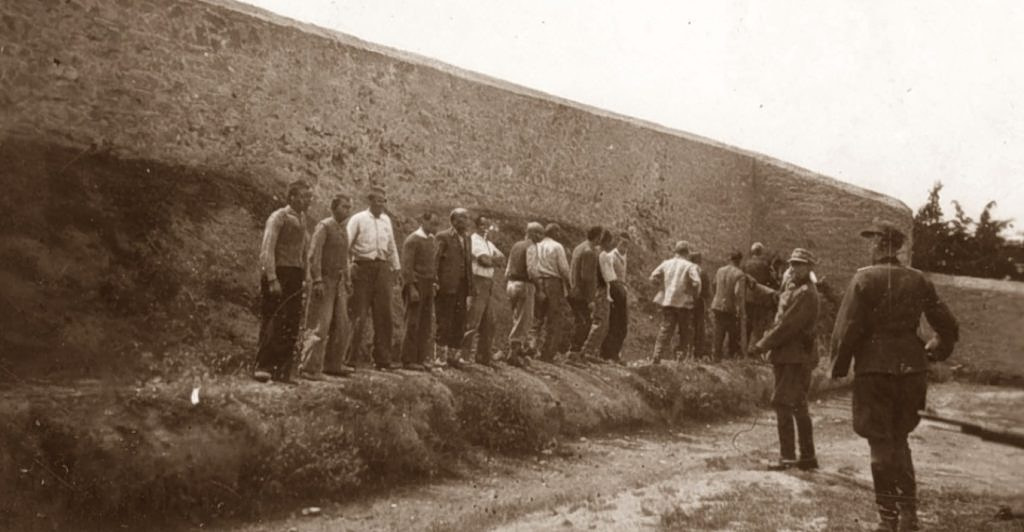

Credit: Alexandros Alexandris

A Chef Formed by Many Kitchens and a Clear Philosophy

Sinanaï belongs to a generation of chefs who built their path through experience across different kitchens and cultures. His trajectory—marked by collaborations with leading international chefs and work in demanding restaurants—has been driven by a constant need for evolution and experimentation.

His contact with Japanese, Cantonese and Mediterranean gastronomy shaped a philosophy that avoids “impressive imitation” in favor of meaningful synthesis: clean flavors, respect for the raw material, and a distinct relationship with fire.

Now, as executive chef at Tribeca, he creates dishes that aim to balance technique and emotion. He speaks less about recipes and more about mindset—seeking not excess, but the “quiet strength” of a plate that holds its ground every day in a working kitchen.

“If I Lose the Love, I Lose Everything”

For Sinanaï, cooking did not begin as a profession. It began as instinct.

He describes growing up in an environment where food wasn’t just necessity, but an act of care—a way to show respect and love. He entered professional kitchens to work and survive, but realized early he could not do anything else: what kept him upright was not the salary or title, but fire, process and creation.

After two decades in kitchens, he says, cooking remains first and foremost love, and only then a profession—because without that love, “everything is lost.”

The Lessons of Precision and Humility

Asked about working with acclaimed chefs such as Heinz Winkler and Tong Chee Hwee of Hakkasan, Sinanaï frames those experiences as schooling in different philosophies with the same core: absolute respect for detail and zero tolerance for “almost.”

From Winkler, he says, he learned discipline and precision—an understanding that high gastronomy is not performance but the product of deep knowledge, repetition and respect for technique. From Tong Chee Hwee and the Hakkasan environment, he describes learning how tradition can be translated into contemporary language without losing its soul—where innovation comes not from excess but from control of the raw material, the fire and balance.

The biggest lesson, he says, is that the kitchen does not forgive ego: only consistency, the team and the result on the plate speak.

Criticism, Failure and Calm as a Strength

The moment he realized he had “fallen into the deep end,” Sinanaï says, wasn’t dramatic. It came when he found himself leading—with responsibility not only for the plate, but for people, rhythm, decisions and outcome.

He describes the kitchen as a space of constant evaluation—from the customer, the team, partners, and above all oneself. Harsh criticism, he says, is not easy to accept, but over time he learned to separate the kind that builds from the kind that merely vents.

Wrong decisions—on collaborations, timing, even overestimating endurance—became turning points. Passion alone, he says, does not protect you; you need judgment, boundaries and clarity. What ultimately shaped him, he argues, was not success but failure—the kind that matures you, makes you fairer to people and calmer with yourself. And that calmness, he says, is now his greatest strength.

Family, Trahanas and “Education Without Words”

On social media, Sinanaï often appears cooking with his son, creating short videos that reveal a different side of him: a father who sees the kitchen as a tool for upbringing and communication.

For him, cooking is a way to teach children respect, patience and a conscious relationship with food—not through rules and prohibitions, but through example. What he wants to instill first, he says, is contact with the raw material: understanding where food comes from, respecting it, and not taking it for granted.

Asked about comfort food that connects him to the past, he names a single dish: his grandmother’s trahanas, which his mother still makes today—simple, but filled with memory and love.

Meal prepared by Alsi and David. Credit: Alexandros Alexandris

What He Cooks at Home and What Follows Him Everywhere

At home, he says he often cooks beef or lamb heart, simply—oregano, garlic and a little lemon at the end. He calls it food of substance: nothing wasted, the raw material honored whole, made not to impress but to nourish and unite. He says his wife and son enjoy it, and that they are waiting, gradually, for their seven-month-old to try it too—another small sign of food passing from generation to generation as an act of care.

In his professional life, one dish follows him everywhere: beef tartare. He describes it as a “canvas” that allows him to express the place and philosophy of each kitchen without losing the core. In a Mediterranean version, it is pared back—olive oil, fleur de sel, lemon, oregano and Kalamata olives. In a Japanese approach, it shifts toward soy and a subtle mix of five spices, while keeping the same respect for the raw material.

Projects With “Substance and Duration”

As for what comes next, Sinanaï says he is investing in projects with substance and longevity—ventures that connect cooking with education, family and real life, not merely exposure. He speaks of ideas grounded in raw material, fire and the transmission of knowledge, with a clear identity and reason for being.

He also underlines his wife’s decisive role: from his website to his overall image and the way his work is communicated. He describes her as the filter of what is worth putting out—and as a point of balance who helps turn experience and ideas into something structured and consistent, without losing their truth.

TV as a Tool — Not a Destination

Looking back, he says television played a role, but not the one people often imagine. It didn’t teach him to cook or define him; it was a tool of visibility—an acceleration of recognizability. The real work, he says, had already been done through hours, mistakes and consistency.

He would recommend TV to someone starting out only if they have first clarified why they cook and who they want to be—not as a goal, but as a means.

Credit: Alexandros Alexandris