The human brain—complex, unique, extraordinary. An “orchestra” organ of the entire body, a perfect electrochemical computer with unimaginable capabilities. Who would have thought that the intelligent, multidimensional human brain owes much of its remarkable properties to… the gut and the bacteria that inhabit it?

And yet, this is what a new study recently published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) shows. The study is based on experiments that, to non-specialists, seem straight out of a science fiction film. In these experiments, gut bacteria from primates were introduced into mice, and the brains of the small rodents began to develop characteristics and functions similar to those of much larger primates.

No, the goal of these experiments was not spooky—it was far more important. The experiments, conducted by researchers at Northwestern University in Illinois, USA, essentially demonstrated for the first time that gut bacteria play a hidden but critical role in shaping the human brain and likely continue to influence it, affecting disorders such as neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions. In other words, changes in the gut microbiome have a direct impact on brain function.

Humans have the largest brain relative to body size of any primate species. Yet scientists know little about how mammals with large brains evolved to meet the enormous energy demands required for brain growth and maintenance.

A Vital Question

Now, researchers at Northwestern University, led by Associate Professor of Biological Anthropology Katherine Amato, have provided the first experimental evidence that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in shaping brain functions. As Dr. Amato told VIMA-Science: “Our study shows that the gut microbiome influences traits associated with human brain development.”

These unexpected findings build on earlier research from Dr. Amato’s lab, which showed that gut bacteria from primates with larger brains produce more metabolic energy when introduced into mice. This additional energy is vital: the larger the brain, the greater the “fuel” it needs to grow and function.

In the latest study, the team went further, examining the brain itself and its function. The key question: could gut bacteria from primates with different brain sizes alter the function of the comparatively smaller brains of mice?

A Clever Experiment

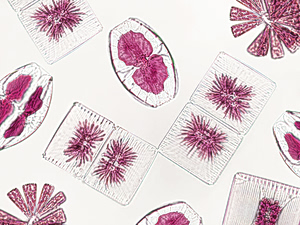

To answer this, researchers conducted a strictly controlled lab experiment. They introduced gut bacteria from two primates with large brains (humans and squirrel monkeys, a Saimiri species found in Central and South America) and from one primate with a small brain (rhesus macaques) into mice that lacked a gut microbiome.

Eight weeks later, the results were striking. Clear differences appeared in the mice’s brain activity. Mice receiving bacteria from the small-brained primate showed different patterns of brain function compared to those receiving bacteria from larger-brained species. As Dr. Amato explained: “In mice that received bacteria from large-brained species, we observed higher activity in genes associated with energy production and synaptic plasticity—processes that allow the brain to learn and adapt. At the same time, these pathways were far less active in mice receiving bacteria from the small-brained species. We were able to compare the data from mouse brains with data from the brains of macaques and humans and were astonished to find that many gene-activity patterns were identical. In other words, we were able to make mouse brains function like primate brains using only gut bacteria.”

A Crucial Interaction

How does the gut microbiome shape the brain? Through which pathways? Dr. Amato explained: “We believe three main pathways are involved. First, a direct pathway via the enteric nervous system and the vagus nerve—the longest cranial nerve connecting the brain to organs including the heart, lungs, and gut. Second, interactions with the immune system. Third, the production of neurotransmitters and other molecules that travel from the gut to the brain via the bloodstream. These processes are dynamic—they shape the brain during development and continue to affect its function throughout life.”

Her claims were further supported by another surprising finding. Mice receiving gut microbes from macaques with smaller brains showed gene activity patterns associated with ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism. “Our results suggest that gut bacteria contribute to these disorders. The gut microbiome appears to shape brain function during development. If the human brain is exposed to the ‘wrong’ bacteria early in life, its development can change, potentially leading to neurodevelopmental symptoms.”

The gut microbiome has also been linked to mental health. Dr. Amato noted: “Gut bacteria are believed to influence psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression via pathways involving serotonin and dopamine production.”

Future Possibilities

What does this mean in practice? Could introducing the “right” bacteria into humans alter or even prevent certain disorders? “First, it is important to stress that our findings mainly help us understand the root of certain psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders by allowing us to view brain development through an evolutionary lens. Theoretically, it may one day be possible to administer gut bacteria to modulate brain function, but that is far off. What our research shows is that exposure to the right gut bacteria during development is crucial for healthy brain function. Future studies will need to identify these specific bacterial types to ensure infants are exposed to the right bacteria to promote proper brain development.”

Could we one day even enhance human intelligence through the gut? “We currently have no evidence that gut bacteria can directly affect intelligence. What we see is that they play a critical role in brain development and function. This connection may influence brain disorders but does not mean there are gut bacteria that make someone smarter.”

The research team, however, plans to deepen its understanding of the gut-brain relationship. Dr. Amato outlined the next steps: “Our next goals are to study more primate species to see if the patterns we found apply to others with larger or smaller brains. We also aim to further explore which bacterial functions drive the patterns we observed.”

Until then, it seems safe to remember: healthy brain function starts in the gut—and we should act accordingly.

Bacterial Species with the Greatest Impact

We asked Dr. Amato if her team had identified gut bacteria species with the greatest influence on the brain. She replied: “We did not find a clear pattern linked to specific bacterial species. It appears that multiple microbial functions, performed by many gut bacteria types, affect the brain. For example, we observed increased levels of short-chain fatty acids in mice receiving bacteria from large-brained primates. These fatty acids, produced when bacteria break down plant fibers, play a crucial role in energy production, immune function, and gene expression. There is a subset of gut bacteria that produce these fatty acids, and this is now the focus of our research.”