Seven years after Greece’s exit from the bailout memorandums and the extremely harsh austerity imposed by its creditors, the country is still struggling to devise a comprehensive approach to restructuring its economic model to correct decades-long pathogenies, from partisan clientelism to the absence of long-term planning that will enable it to meet major challenges in a rapidly changing global economy.

It is a task that, despite the decade-long economic great depression, has not been undertaken in earnest by the country’s political class, despite frequent rhetorical pronouncements regarding its urgency.

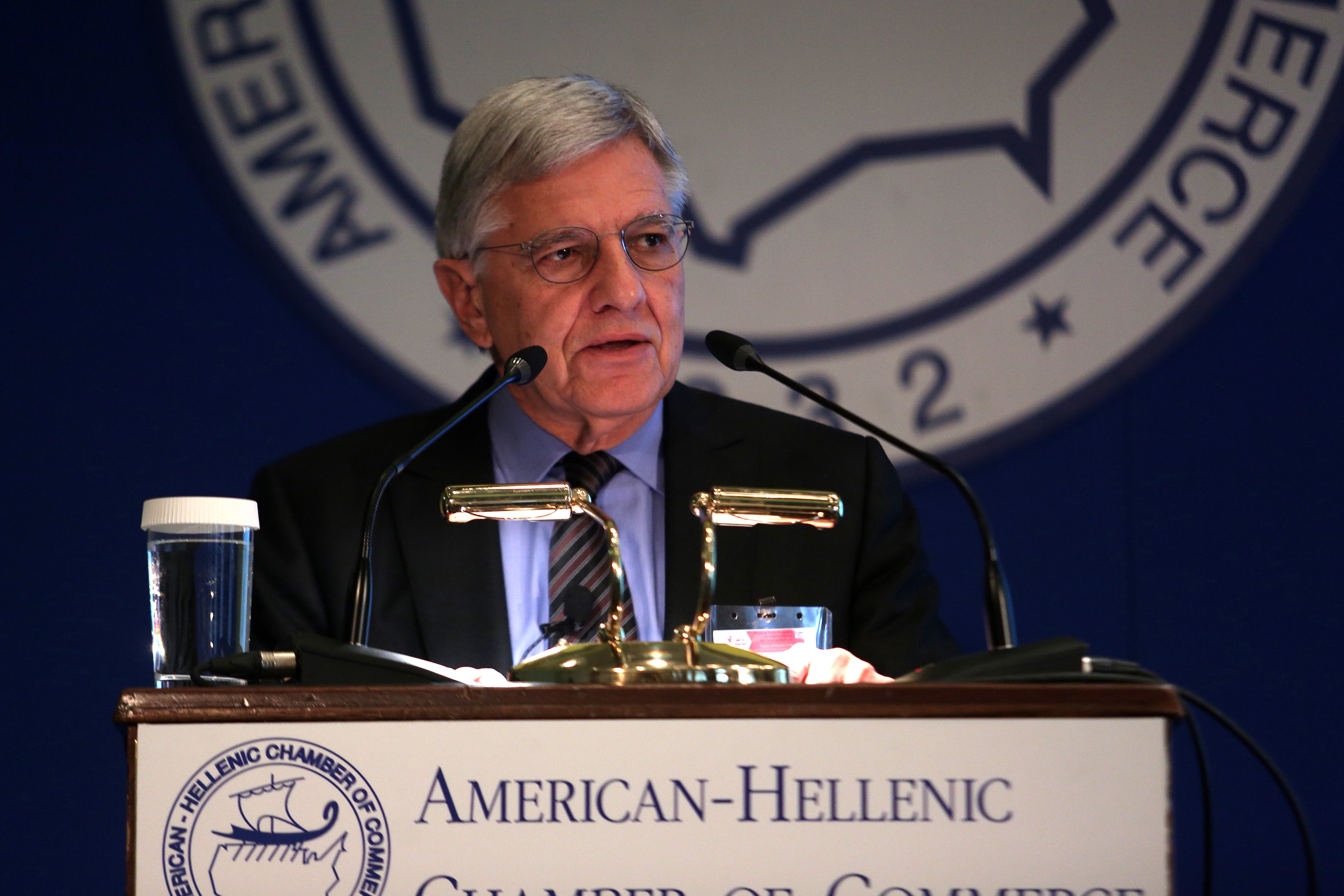

Explaining the necessary framework for this overarching objective is precisely what Tasos Giannitsis, Athens University Professor Emeritus of economics and minister in various PASOK governments, achieves in a monumental new study entitled Greece 1953-2024: Chronos and Political Economy, a product of both academic and political experience.

He combines and explains economic, political, social, and international developments that impacted postwar Greece.

Giannitsis argues that today it is imperative that the state and the political system do what they have failed to do for decades: implement comprehensive policies across a wide range of issues, guided by the most important medium-to-long-term collective and social objectives. Yet, he recognises that this would constitute a major rupture in deeply entrenched balances of interest, and for this reason is systematically set aside.

Has Greece ever had a strategy—a genuine redistributive policy beyond subsidies—taxing capital for the benefit of the lowest income groups?

There has never been a systematic redistributive policy. An attempt was made—and achieved—to strengthen low incomes by the first government of Andreas Papandreou in the 1980s. We can still see today, from opinion polls, how that period has left its imprint, as it was perceived as a popular policy. After the political and economic developments of the first two postwar decades, Greece needed such a shift. However, low incomes were strengthened without significant redistribution. The burden fell on government borrowing, which increased substantially due to fiscal deficits, and to a much lesser extent on the productive system and increases in daily wages.

Inequalities at the time were large. The share of profits from the GDP—which was then the highest among OECD countries—was somewhat reduced, without falling to the levels of other countries, and correspondingly the share of wages increased somewhat. In the following decades, inequality increased due to benefits and other advantages that do not appear in incomes (unauthorized construction, tax exemptions, preferential practices, etc.), but nonetheless affect inequalities in our society to the same extent. Greece remains among the top five countries with high inequality in the EU, which shows that despite the weight of social policy, other processes are operating in the economy that negatively offset the effects of social policy.

What were the causes of Greece’s deindustrialisation, and who benefited from it?

Deindustrialization in the 1970s and 1980s was a broader trend in many countries. Greek industry, having been created under conditions of strong state protection until 1980 (high tariffs and taxes on imports, preferential loans, multifaceted state subsidies, and the absence of efforts to increase the technological base and productivity), was not competitive. As a result, with the opening to international markets and the abolition of state protection, many firms could not survive, and often did not even attempt to do so through restructuring strategies, and closed. As mentioned, the phenomenon was more general, due to the rise of services and competition as new drivers of growth, but the consequences for Greece were more severe than in many other countries.

The stock market boom and bust of 1999 led to a massive loss of capital and the ruin of hundreds of thousands of small investors. What was to blame? The naivety and greed of the public, inactive regulatory authorities that allowed many shell companies to be listed, latent government support through certain ministers, or all of the above?

The stock market bubble was mainly due to a strong speculative trend that gradually spread throughout society and led people who until then did not even know what the stock exchange was to invest their savings, disregarding any rational warning.

The 1998 decision to include the drachma in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism inherently signaled an extremely positive outlook for interest rates, stability, inflation, economic growth, and corporate profits. This fueled a fever of expectations and stock market investments, which after a certain point created what is technically referred to as “herd psychology and behavior.”

International experience shows that when such phenomena develop, the usual tools for addressing the problem are insufficient. At that point, any sober warning was met with incredible attacks “from below,” accusing those who voiced them of serving illicit interests and manipulating stocks to their advantage or disadvantage.

I recall that Stavros Thomadakis (chairman of the Hellenic Capital Market Commission), Theodoros Karatzas (Governor of the National Bank of Greece), and Lucas Papademos (Governor of the Bank of Greece) publicly warned the investing public about the pathology of developments. The criticism from the press, the opposition at the time, and society was overwhelming. Certain individuals suffered unjust, multi-year legal prosecutions over this, which ultimately came to nothing.

There were very isolated ministerial exhortations [to invest]. That was misguided. However, I do not believe that these created or incited the stock market fever. Ultimately, however, one positive element was that the macroeconomy was not affected by the bubble.

At the level of income redistribution, estimates of gains and losses are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to make, as one would need to take into account complex developments in purchases, sales, and prices that are not available.

In short, let us not always seek an external factor to justify irrational behavior. In certain cases, such factors may play a role. But we ourselves are always at the center.

Eight years later, we drove a dynamic economy to a shipwreck, alone among all the EU countries. In stock market matters, let us examine what speculative behaviors, perceptions, and choices we made at the time as a social whole, disregarding all logic and principles of prudence regarding our savings and assets.

Did Greece effectively exploit its entry into the Eurozone (EMU), and if not, why and how should it have done so?

The single currency was associated with new rules of the game in monetary and fiscal policy, as well as in the functioning of the political system. It meant that Greece lost the ability to devalue its currency, the ability to administratively set borrowing interest rates for businesses, households, and the public sector, and the recourse to fiscal deficits—all of which had repeatedly led in the past to major social and macroeconomic destabilisations.

Under the new conditions, Greek politics assumed that monetary risks had been eliminated and completely overlooked the fact that a single currency with a fixed exchange rate (within the EMU) required discipline under the new rules, and that maintaining behaviors and policies characteristic of the unstable national currency in the pre-EMU era would inevitably cause major internal destabilisations.

Thus, in the period after 2001, very significant increases were granted in wages and pensions, borrowing by households, businesses, and the public sector increased explosively, massive new hires were made in the public sector (after 2005), and public spending rose significantly, partly due to the deficit-ridden social security system. All of this led to the collapse of the economy and to the brink of bankruptcy in 2009–2010.

Nevertheless, entry into the EMU gave the country enormous credibility at the time, which played a critical role in Cyprus’s accession to the EU. Moreover, even in the most painful moments of the fiscal crisis, the EMU functioned as an “anchor” and as support for the country, enabling massive lending from other member-states and preventing the extreme impoverishment of Greek society and its collapse for decades.

Tasos Giannitsis with the late Former Prime Minister of Greece, Kostas Simitis.

For decades—especially after 2010—there has been extensive discussion about the need to restructure the country’s productive model, yet absolutely nothing has been done. What accounts for this, and what strategy would you propose?

The most obvious answer when something that seems necessary is not done is that we either do not want to or cannot do it. Here we encounter a critically important difference between Greece and other emerging countries (China, South Korea, Spain, Portugal, etc.), which started from roughly the same point but achieved very different results over time. Greek policy either did not want to, or failed to, focus on production specialisation, productivity, and the country’s strength. It favored the creation of a productive system closely tied to the state, but one without developmental dynamism.

Both industry and services are concentrated in forms of low-productivity, low- or medium-technology-intensive production, which in turn determine the country’s low performance, as well as low wages, weak capacity for evolution, and ultimately even weak macroeconomic outcomes.