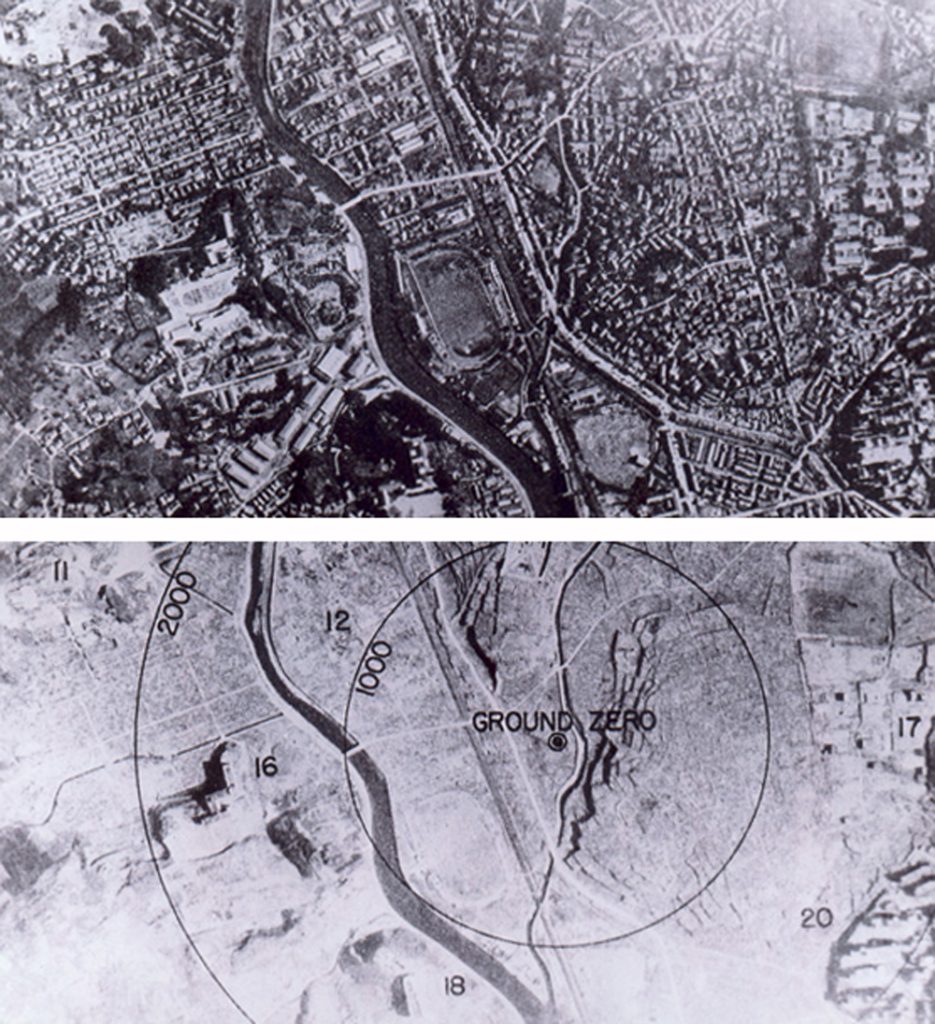

On August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m. local time, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, at 11:02 a.m. on August 9, a second bomb was detonated over Nagasaki. These twin attacks brought World War II to a cataclysmic close—and forever altered the fate of humanity.

Two Bombs, Unimaginable Destruction

Japan, aligned with the Axis powers but already effectively defeated by May 8, 1945, remained under military focus as United States forces sought to end the war decisively.

Within seconds of detonation, both cities were transformed into apocalyptic wastelands. Tens of thousands perished instantly; countless more succumbed in the following months and years to radiation-induced illnesses.

A comprehensive study by Alex Wellerstein for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimates 110,000 deaths in Hiroshima and 55,000 in Nagasaki, along with sharp increases in leukemia, cancers, and birth defects.

Real-Time Reports: Chaos and Collapse

Contemporary coverage from To Vima (August 9, 1945) relayed scenes of chaos from Guam and Japanese radio: “In Hiroshima, those inside buildings were incinerated. Those in the streets died from pressure and heat. Medical facilities were destroyed, and aid became improvised. Two-thirds of the city was obliterated. Commanders likened the impact of one atomic bomb to 2,000 B‑29 raids.”

On August 10, To Vima reported the Nagasaki bomb: “Nagasaki, population 200,000, was erased. The atomic bomb’s results exceeded expectations, despite winds that lessened the blast’s full potential.”

Different Bombs, Shared Tragedy

Remarkably, the two bombs were chemically distinct:

- Hiroshima received a uranium‑235 device (~15 kt yield)

- Nagasaki was hit by a plutonium‑239 bomb (~21 kt)

Particle physicist Th. K. Geranios noted these tests were essentially human experiments in contrasting bomb types. Though the Nagasaki bomb was more powerful, wind conditions meant fewer casualties (~70,000) than initially predicted.

Why the U.S. Decided to Strike

At the time, President Harry Truman defended the attacks as necessary to end World War II and save American lives. Critics argued motives ranged from demonstrating strength to the Soviet Union to justifying the two billion-dollar Manhattan Project.

According to Le Nouvel Observateur and archival research, however, predictions of U.S. casualties during a land invasion of Japan were probably overstated. Some internal documents reveal projections closer to 46,000 deaths, not the 500,000 often cited—a disparity suggesting potential political motivation behind the bombings.

Surrender and Legacy

On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s unconditional surrender—marking the first time in Japanese history that an emperor addressed the nation directly via radio.

The death toll from both bombings is now believed to exceed 200,000, a figure compounded by long-term health effects from radiation exposure.