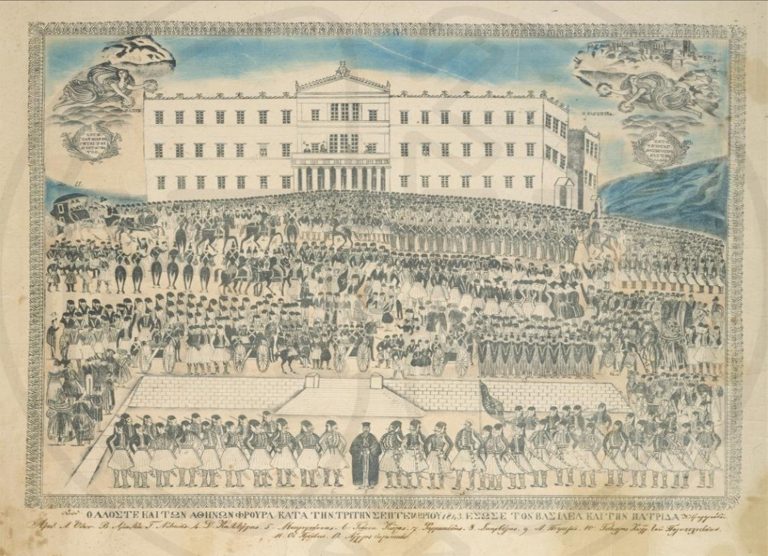

On the night of September 3, 1843, the streets of Athens filled with restless energy. Citizens, politicians, and soldiers gathered outside the royal palace, rallying against the autocratic rule of King Otto, Greece’s first monarch after independence. Their demand was clear and uncompromising: a constitution.

It was a moment that altered the young nation’s trajectory. Until then, Otto—an imported Bavarian prince placed on the throne after Greece’s liberation from Ottoman rule—governed as an absolute monarch. But as voices of dissent grew louder, the uprising forced him to concede. Within months, the first constitution of the independent Greek state was born in 1844.

A fragile compromise

The new constitution established a constitutional monarchy. Legislative power was shared between the king, parliament, and a senate appointed for life by the monarch. Individual freedoms were formally recognized, but justice still “flowed from the king,” who retained the right to appoint judges.

Ioannis Kolettis (centre), then ambassador of Greece to France, in Paris in 1842 with Jean-Gabriel Eynard (far left) and his wife Anna Eynard next to him. Public domain via Wikipedia commons

Historians describe the document as cautious and conservative, reflecting fears that too much democracy might be “dangerous for nations still young in civilization.” Indeed, Otto continued to interfere in elections, manipulate press freedoms, and dominate political life. Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis, who rose to power in this period, cemented a culture of corruption, favoritism, and nationalist rhetoric that would mark Greek politics for decades.

A second, more radical revolution

Two decades later, on October 10, 1862, a broader uprising erupted. Once again, soldiers and civilians joined forces—this time with even greater popular backing. Otto was overthrown, and with him, the rights of Greece’s first dynasty vanished.

The Revolution of 1843. Public domain via Wikipedia commons

The new constitution of 1864 was revolutionary for its time. It abolished the senate, enshrined popular sovereignty, and introduced universal male suffrage—a progressive step unmatched in much of Europe. This framework endured, revised in 1911, and with the introduction of parliamentary rule in 1875, it gave Greece half a century of relative political stability.

Why September 3 endured in memory

Curiously, while the 1862 revolution was more decisive, it is September 3, 1843, that lives on in Greek national memory. The date became a symbol of democratic resistance against royal overreach. Its principles, often violated in practice, continued to inspire new generations whenever freedoms were curtailed—well into the 20th century.

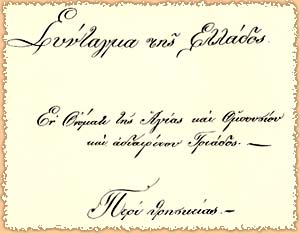

In the name of the Holy, Consubstantial and Indivisible Trinity…are the first words of the Greek Constitution of 1844. Public domain via Wikipedia commons

Even in modern times, the symbolic power of the date remained. In 1974, after the fall of Greece’s military dictatorship, a new political movement deliberately chose September 3 to launch its manifesto, tying its vision of democracy to the spirit of 1843.

Today, standing in Syntagma Square—so named after that very night, when citizens demanded a σύνταγμα (constitution)—is to stand on the ground where Greece first claimed its constitutional destiny. September 3 is remembered not just as an event of the past, but as an enduring reminder of the struggle for democratic rule.