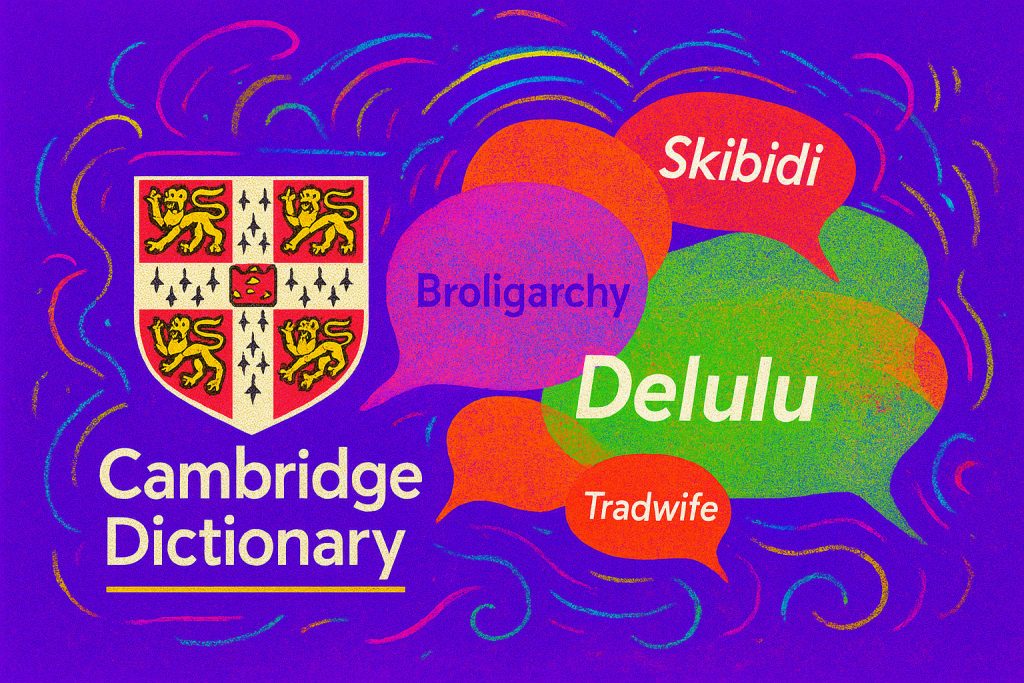

The way we communicate online is rapidly reshaping the English language — and now the world’s leading dictionaries are taking notice. The Cambridge Dictionary has announced the addition of 6,212 new words, many of them born on social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, as well as in conversations with AI chatbots.

Among the most eye-catching entries are “skibidi,” “delulu,” “tradwife,” “broligarchy,” and “inspo,” terms that have quickly migrated from memes and subcultures into mainstream digital language.

“Delulu,” a shortened form of “delusional,” is one of the most widely used. It has been adopted by younger generations to describe unrealistic optimism, often humorously. Earlier this year, it even appeared in the Australian Parliament, when Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described his rivals as “delulu with no solulu.”

Another viral word, “skibidi,” stems from the surreal YouTube series Skibidi Toilet, where toilet-headed characters battle humans with CCTV-camera heads. According to Cambridge, it can mean something cool, bad, or simply nothing at all — often used just for fun.

Some additions carry political undertones. “Broligarchy,” a blend of “bro” and “oligarchy,” refers to the billionaire tech elite, while “tradwife” describes women embracing ultra-traditional roles as wives and mothers, a trend linked to online communities supporting conservative politics.

Colin MacIntosh, Programme Manager at the Cambridge Dictionary, explained: “It’s unusual to see words like skibidi and delulu in the Cambridge Dictionary. We only add terms we believe will stand the test of time. Internet culture is changing English, and that’s fascinating both to observe and to document.”

The inclusion of such words has sparked debate, with critics viewing them as linguistic clutter. Yet lexicographers stress that dictionaries must reflect real usage. As Cambridge Publishing Manager Wendelyn Nichols noted: “Think of ‘email’ in the 1990s or ‘hashtag’ in the 2000s. Today, AI and pop culture terms are becoming part of everyday life.”

Greek linguist Christophoros Charalampakēs agrees, pointing out that thousands of new words are already included in the Academy of Athens’ dictionary. “Language is living,” he said. “Lexicographers don’t decide what survives — society does.”

The message is clear: if people use it, it exists.