Shortly after midnight in the early 1990s, a junior Greek diplomat returned from Capitol Hill to the ambassadorial residence on Massachusetts Avenue with news that could not wait until morning. Ambassador Christos Zacharakis was woken and asked to come downstairs from the fourth floor. A telegram to Athens had to be drafted immediately.

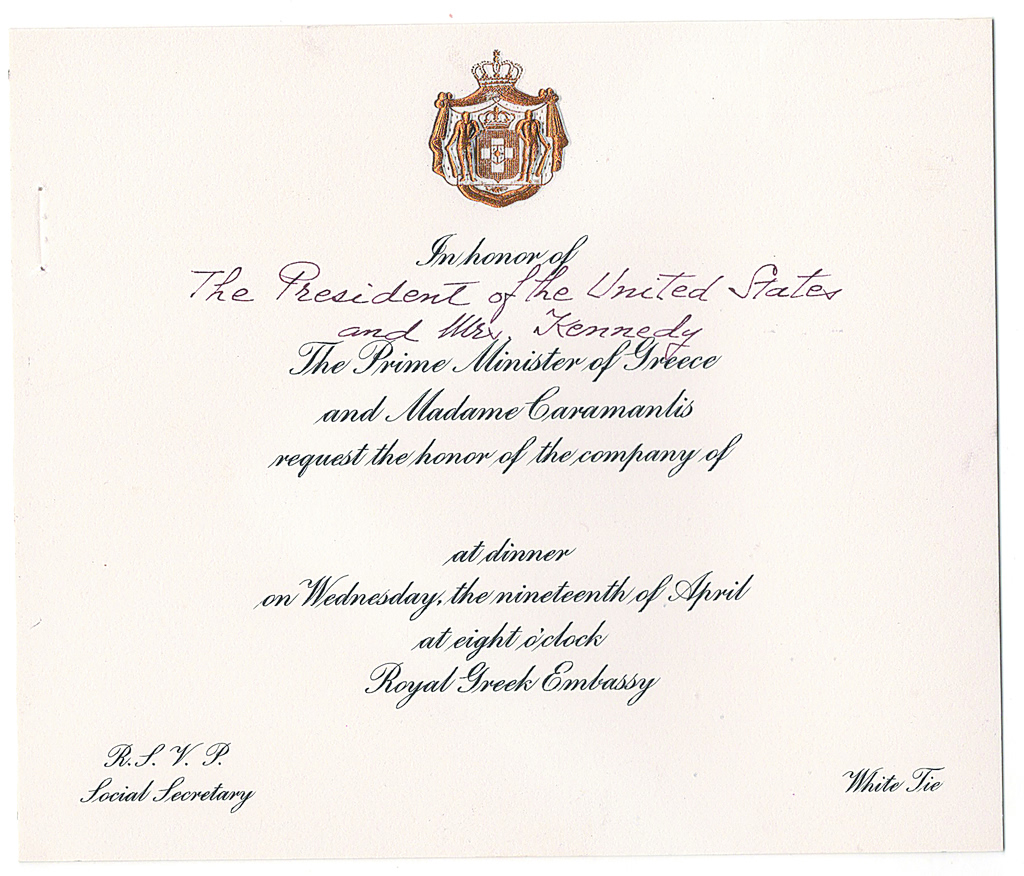

Konstantinos Karamanlis, his then wife Amalia Megapanou (left), John F. Kennedy and his wife Jackie, and Greek Foreign Minister Evangelos Averoff-Tossizza during the official luncheon held in honor of the American president at the Greek Embassy in Washington on April 19, 1961.

Washington had decided that Turkey would no longer receive U.S. military assistance exclusively in the form of grants. Like Greece, it would now come as loans. The long-standing 7 to 10 formula that governed the balance of American military aid between Ankara and Athens had been partially overturned.

Inside the 1906 mansion, the moment passed quickly. The message was sent. The lights went out again. But scenes like this one, improvised, consequential, and largely invisible to the public, defined the building’s role for decades. It functioned not merely as a residence, but as a quiet operating room for Greek American diplomacy.

Nearly thirty years later, the same diplomat returned to Washington to present her credentials as Greece’s ambassador to the United States. This time, Katerina Nasika did not walk through the front door of the mansion.

From her office in the modern embassy complex next door, she could still see the familiar structure standing in place. The shutters were closed. The rooms were silent. For more than fifteen years, the building had remained sealed, its public life suspended.

That silence is now coming to an end.

Following the completion of preparatory work and a formal government decision, the historic residence will enter a full restoration phase beginning next year. For Greece, whose relations with the United States are currently at their strongest point in decades, the project carries meaning beyond architecture or symbolism.

“This is not just a technical undertaking,” Nasika said. “It is an important tool for advancing Greece’s work and presence.”

When a Building Falls Out of Use

The decline of the mansion began in the years when Greece constructed the new political building that now houses its embassy. According to accounts that still circulate among embassy staff, the project followed a familiar pattern. A contractor of questionable reliability secured the work through opaque procedures, failed to follow approved plans, and caused damage to the foundations of the neighboring historic residence.

The contractor eventually disappeared, leaving behind an unfinished site and a structural problem that the embassy would struggle to address for years.

The consequences were swift. The mansion, already vulnerable because of its age, began to exhibit serious structural stress. In 2006, it was closed permanently. Reception rooms that had hosted presidents, prime ministers, and foreign ministers were left exactly as they were, with furniture draped and dust settling along the baseboards. The effect was not one of gradual decline, but of abrupt interruption.

Over the years that followed, successive ambassadors attempted to advance a solution. But the Greek financial crisis made large scale restoration politically and financially remote.

An Unplanned Turning Point

The reversal came almost by accident.

In the fall of 2019, at a state dinner in Athens honoring Chinese President Xi Jinping, Alexandra Papadopoulou had not yet departed for Washington to assume her post as ambassador. Seated beside businessman Achilleas Konstantakopoulos, she mentioned the deteriorating state of the Greek residence in Washington.

By the end of the evening, the remark had led to an unexpected proposal. Konstantakopoulos offered to finance the restoration study in full.

Within months, the donation brought to Washington architect George Skamea and the firm Preservation Design Partnership, specialists in the conservation of historic monuments and public buildings. Their portfolio includes the Alamo Mission, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, and other sites embedded in American historical memory.

The study, costing several hundred thousand dollars, documented the mansion’s condition in detail and mapped out a restoration that would preserve its architectural character while adapting it to the requirements of modern diplomacy. Original wood carvings, marble entrances, plaster ceilings, and even cast-iron radiators from the early twentieth century were catalogued and incorporated into the plan.

For the first time in nearly two decades, the objective was not simply to stabilize the building, but to return it to its original stature. The design includes a renewed ambassadorial residence with six guest rooms, allowing the building once again to host official diplomacy.

Inside the Closed Rooms

Papadopoulou’s arrival in Washington coincided with the early weeks of the pandemic. With the embassy largely closed, a small volunteer team was assembled to enter the mansion, document its contents, and secure what could be saved.

Theodosis Liapis, the embassy’s longest serving employee, and Alexia Papadosafaki, the wife of Theodoros Bizakis, Greece’s current ambassador to Turkey, spent several days moving carefully from room to room. Much of what they encountered had not been touched since the building was sealed.

They recovered archival documents, furniture from the family of General Philip Sheridan, some of the first Greek passports issued in Washington, and correspondence dating back to the postwar period. These materials shed light on pivotal moments in bilateral relations and might easily have been lost.

Many items were rescued just in time. They were transferred to safe storage and systematically recorded for the first time. The restoration plan now includes a dedicated exhibition space, allowing the building’s history to be presented alongside its renewed diplomatic function.

What the Mansion Has Witnessed

Designed in 1906 by architect George Oakley Totten, the mansion occupies a singular position on Embassy Row. A few years later, Totten also designed the Turkish Embassy residence directly across the circle. Greece and Turkey became neighbors in Washington through two buildings conceived by the same architect, a geographical symmetry that mirrored a far more complicated history.

Later, statues of Eleftherios Venizelos and Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the two statesmen most closely associated with the modern founding narratives of their countries and with a shared legacy of rivalry, were placed facing one another across the roundabout.

The mansion was donated to the Greek state in 1937 by William Helis, a Greek American who arrived in the United States penniless and built a fortune in the oil industry. From that point forward, the building became intertwined with critical moments in modern Greek American relations.

In the immediate postwar years, correspondence from the U.S. Treasury concerning Marshall Plan assistance bore the address “Greek Embassy, 2221 Massachusetts Avenue.” For a country emerging from occupation and civil war, some of its earliest connections to American aid passed through those rooms.

On April 19, 1961, as the Bay of Pigs invasion was collapsing into a political disaster for the Kennedy administration, the mansion unexpectedly found itself at the center of events. Despite calls to cancel, President John F. Kennedy attended a reception there in honor of Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis.

As the two leaders exchanged greetings beneath the marble entrance, Theodore Sorensen was finalizing Kennedy’s address to the nation at the White House less than a mile away. The overlap of those moments remains one of the building’s most striking memories, linking Greek diplomacy to one of the first major crises of the Cold War.

In later years, the mansion served as a conduit for communications surrounding Cyprus, including the delivery of Prime Minister George Papandreou’s letter to President Lyndon Johnson. After the Turkish invasion and occupation of the island, the building also became a center for early outreach to Congress, as Greek American advocacy groups began to take shape.

Restoring Presence

For much of the past two decades, the fate of the building appeared disconnected from the relationship it represented. As Greek American cooperation deepened across defense, energy, and regional security, the historic residence on Massachusetts Avenue remained sealed and unused.

That disconnect is now ending.

The required permits are in place, state funding has been approved, and members of the Greek diaspora have indicated their willingness to contribute. Restoration work is expected to begin next year and to last about three years.

One visible change will come early. The statue of Eleftherios Venizelos, a work by sculptor Yannis Pappas, will be moved closer to Massachusetts Avenue, making it visible to drivers entering the city. The sculpture is a reduced scale version of the statue that stands in Freedom Park beside the American Embassy in Athens, with the only identical copy housed at the Benaki Museum.

For the ambassador overseeing the project’s final approvals, the moment carries less a sense of culmination than obligation.

As her term in Washington draws to a close, Nasika describes the project not as an achievement, but as a test. Greece, she notes, will soon possess one of the most modern and historically layered diplomatic presences in the American capital. Preserving it, however, requires discipline as much as vision.

“We have to prove that we are worthy of keeping it,” she said.

After more than fifteen years of silence, the challenge is no longer whether the building can be restored. It is whether it will be allowed to fall silent again.