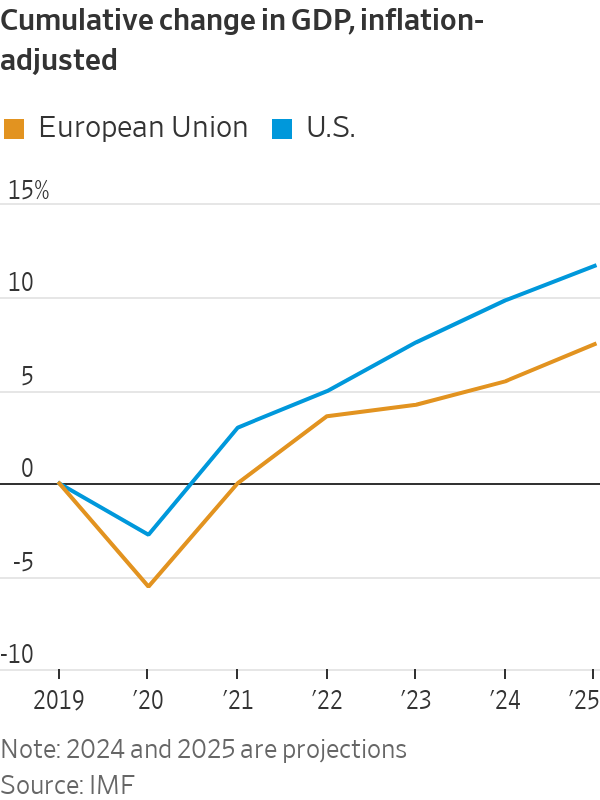

These are humbling times for Europe. The continent barely escaped recession late last year as the U.S. boomed. It is losing out to the U.S. on artificial intelligence, and to China on electric vehicles.

There is one field where the European Union still leads the world: regulation. Having set the standard on regulating mergers, carbon emissions, data privacy, and e-commerce competition, the EU now seeks to do the same on AI. In December it unveiled a sweeping draft law that bans certain types of AI, tightly regulates others, and imposes huge fines for violators. Its executive arm, the European Commission, might investigate Microsoft’s tie-up with OpenAI as potentially anticompetitive.

Never before has “America innovates, China replicates, Europe regulates” so aptly captured each region’s comparative advantage.

The technocrats who staff the EU in Brussels aren’t anti-free market. Just the opposite: they still believe in free trade, unlike the U.S. or China. Much of their regulation is aimed at protecting consumers and competition from meddling national governments.

But there’s a trade-off between consumer protection and the profit motive that drives investment and innovation, and the EU might be getting that trade-off wrong.

For example, to preserve competition, European regulators have resisted mergers that leave just a handful of mobile phone carriers per market. As a result Europe now has 43 groups running 102 mobile operators serving a population of 474 million, while the U.S. has three major networks serving a population of 335 million, according to telecommunications consultant John Strand. China and India are even more concentrated.

European mobile customers as a result pay only about a third of what Americans do. But that’s why European carriers invest only half as much per customer and their networks are commensurately worse, Strand said: “Getting a 5G signal in Germany is like finding a Biden supporter at a Trump rally.” Putting European networks on a par with the U.S. would cost about $300 billion, he estimated.

This has knock-on effects on Europe’s tech sector. Swedish telecommunications equipment manufacturer Ericsson’s sales in Europe suffer in part because many carriers are too small and unprofitable to update to the latest 5G networks. “Europe has prioritized shorter-term low consumer prices at the expense of quality infrastructure,” chief executive Börje Ekholm told me in Davos earlier this month. “I’m very concerned about Europe. We need to invest much more in infrastructure, in being digital.”

Of course, Europe’s economy underperforms for lots of reasons, from demographics to energy costs, not just regulation. And U.S. regulators aren’t exactly hands-off. Still, they tend to act on evidence of harm, whereas Europe’s will act on the mere possibility. This precautionary principle can throttle innovation in its cradle.

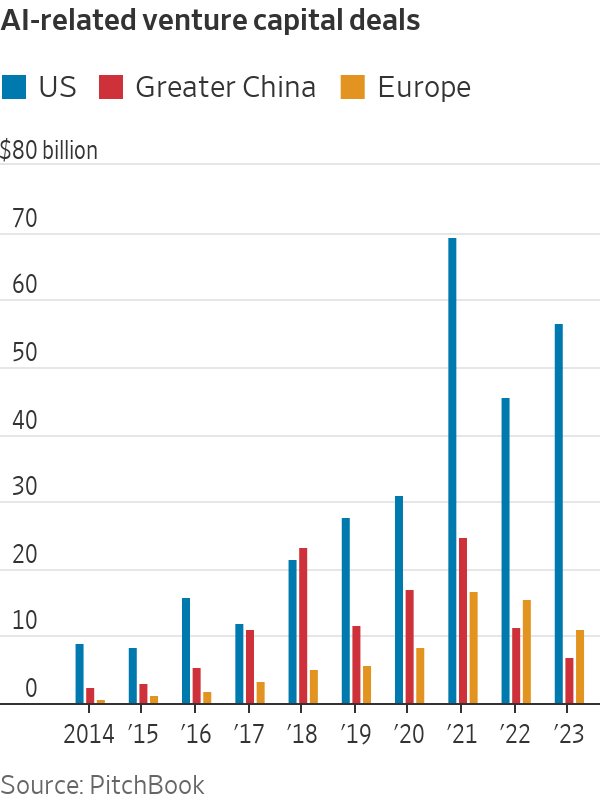

Starting in 2018, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, imposed strict requirements on websites’ collection and use of personal data with fines of up to 4% of global sales. A study by University of Maryland economist Ginger Jin and two co-authors found this depressed European venture-capital investment relative to the U.S. over the next two years. Investors might have shunned business models that weren’t in compliance with, or less valuable because of, GDPR, they said.

History might be about to repeat with AI. Since 2021, AI-related venture-capital deals have raised $44 billion in Europe, roughly equal to China but just a quarter of the U.S., according to PitchBook, and the gap is growing. Last year Europe’s AI industry warned lawmakers their AI law could “lead to highly innovative companies moving their activities abroad [and] investors withdrawing their capital.”

The draft law was watered down, and days later France’s Mistral AI, which aspires to be a European rival to OpenAI, closed a funding round valuing it at around $2 billion, according to Bloomberg.

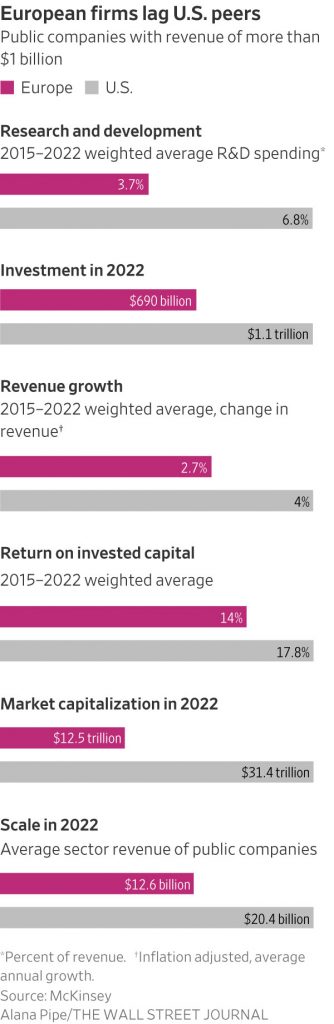

European regulation has a protectionist element, often crafted to hit American tech giants while sparing indigenous startups. Despite that, European startups rarely become giants, and even established companies are smaller than their U.S. counterparts.

“I don’t think that the lack of winners in recent decades can be attributed to a single monocausal factor,” one European-born founder of a U.S. tech company told me. But Europe’s regulatory culture, including prosaic tax and labor laws, is near the top, he said. “Simply granting stock options, for example, is pretty difficult in most European countries. It’s famously difficult to part ways with hires that turn out to be misfits.”

In a recent study, the McKinsey Global Institute noted Europe’s internal market is larger than China’s and almost as big as the U.S.’s. But when it compared companies with more than $1 billion in revenue, the U.S. firms spent 80% more on research and development, boasted 30% higher return on capital, and 1.3-percentage points faster revenue growth.

As the U.S. and China put more muscle into their technological contest, Europe risks falling even further behind. China spends 2% to 5% of GDP on industrial policy—support of sectors deemed strategic—compared with Europe’s 1%, McKinsey said. In December, Brussels approved up to $1.3 billion of aid over eight years for cloud computing-related R&D, but that’s just 4% of what Amazon’s cloud division invests in a year, McKinsey noted.

If Europe is going to compete with the U.S. and China, it will need to rethink its balance between regulation and innovation. As German economy minister Robert Habeck observed last fall: “If Europe has the best regulation but no European companies, we haven’t won much.”

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com