Can commercial ships go nuclear?

The idea of powering commercial ships with nuclear energy has been talked about for decades, but has never moved forward because of costs and safety concerns. And it is still expected to be several years before such ships ply the oceans.

But some momentum toward that goal may be starting to build, thanks to a new generation of reactors and some support from the Trump administration to explore nuclear-powered shipping as part of the effort to revive U.S. shipbuilding.

The new reactors are smaller and less dangerous than the reactors that currently power a handful of U.S. and Russian navy ships, submarines and icebreakers, according to a paper published by a group of nuclear scientists and naval architects at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in October. These reactors—being built by Westinghouse, Babcock & Wilcox and others—are awaiting certification by various regulators for use in commercial shipping, among other industries.

The research paper, funded by some of the world’s biggest shipowners, builders and registries, aims to move nuclear-powered commercial shipping forward by offering suggestions on designing and safely using nuclear-powered vessels.

Here’s what to know about the possibility of nuclear-powered commercial ships.

What are the advantages?

Operating expenses would be much lower for nuclear-powered ships, because there would be no need for refueling for the lifetime of the vessel, which is around 25 years. Currently, fuel makes up nearly half of a ship’s operating expenses.

Also, nuclear power doesn’t produce any carbon emissions. Ships emit about 3% of global carbon dioxide, according to the International Maritime Organization, the United Nations’ maritime regulator. Other alternatives to fuel oil that have been used in commercial shipping—like methanol, ammonia and natural gas—are either in short supply, toxic to the environment or cut emissions by only around 25%.

The lack of emissions means nuclear-powered ships wouldn’t be subject to emission charges that shipowners will have to pay to governments starting in 2028 under International Maritime Organization rules.

“Nuclear commercial shipping represents a viable path to achieving large-scale decarbonization,” says Evangelos Marinakis , chairman of Greece-based Capital Maritime & Trading, which operates more than 150 vessels. “Its successful implementation could bring substantial benefits to a wide range of stakeholders, including shipping companies, shipbuilders and regulators.”

Capital Maritime gave the MIT team the blueprints of the Manzanillo Express, a containership, so they could create and test a computer model of a ship retrofitted with nuclear propulsion.

What are the challenges?

The cost of a nuclear-powered ship could be an issue for many shipowners—it’s four times that of a conventional ship. That would be more than offset by the savings on fuel costs over the life of the ship, but it is a steep initial outlay.

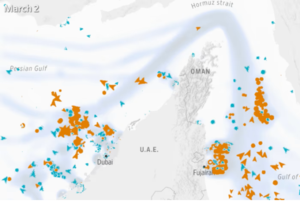

Also, a lot of uncertainty still surrounds the potential use of such ships. There is not yet any regulatory framework for operating nuclear-powered commercial ships, nor any diplomatic agreement on allowing such ships into territorial waters and harbors around the world.

Ship registries and some of the big maritime nations—Japan, Greece, the U.K., France and China—are discussing the infrastructure needed at ports to bring in nuclear-powered ships, as a first step toward resolving the issues surrounding the ships. And a recent memorandum of understanding signed by the U.S. and U.K. calls for looking into the uses of nuclear energy at sea and the establishment of a maritime shipping corridor across the Atlantic Ocean—at a safe distance from other shipping routes—where nuclear-powered ships could be tested for emergencies like engine malfunctions and flooding.

Public acceptance is another hurdle. People need to be persuaded that these ships are safe.

How safe would they be?

The new reactors have a 4% enriched uranium capacity, compared with more than 90% in older reactors, which means that if there was a leak there would be far less contamination. But, at least in theory, when a ship crashes or sinks there should be no radiation leak; the reactor would shut itself down.

The MIT researchers used the computer model of the retrofitted Manzanillo Express to test the vessel’s integrity under simulated extreme conditions like sinking, flooding, extreme weather, loss of power or a fire.

“We demonstrated that retrofitting a microreactor into a conventional diesel-powered vessel is both technically and financially feasible,” says Themistoklis Sapsis, a professor of marine technology and director of MIT’s Center for Ocean Engineering. “The converted ship design satisfies all safety standards to survive a collision without nuclear leaks.”

How soon might they be coming?

The MIT study concluded that the first nuclear containerships could hit the water over the next decade. But that might be a tall order, because of the need for a regulatory framework and broad diplomatic agreement on how and where such ships can operate.

Among the issues to be worked out are emergency-response frameworks, including crew training; port security measures; and safe scrapping of ships at the end of their life cycle.

In the U.S., President Trump has said he wants to revive American shipbuilding , and two administration officials said nuclear-powered ships could help do that. They claim the U.S. is at least five years ahead of other countries in the race to build the new reactors and deploy them on ships.

They said the administration has identified several potential commercial pathways for the use of nuclear energy at sea, including floating power-generating platforms and desalination plants that could be deployed to help with power outages caused by hurricanes, snowstorms, droughts and earthquakes.

Another idea being considered is ports that would use nuclear power to generate electricity for their own use and for docked vessels. Even floating nuclear-powered AI data centers are being considered.

“We’ll see some power-producing ports before 10 years’ time” and eventually nuclear-powered containerships, says Christopher Wiernicki , chief executive officer of the American Bureau of Shipping, which will have to certify the safety of nuclear-powered vessels. Vessels can’t sail legally without being certified.

The bureau is working on establishing standards for certification of nuclear-powered ships, Wiernicki says.

Costas Paris is a Wall Street Journal reporter based in New York. Email him at costas.paris@wsj.com .