IZNIK, Turkey—Archaeologist Mustafa Şahin spent years studying the area around Lake Iznik, near Istanbul. Eventually, he realized that the biggest treasure was hidden in the lake itself.

An aerial photo taken in 2014 revealed the unmistakable layout of a church below the surface of the water. More recent findings strongly suggest it wasn’t just any church, but the venue of one of the most important events in Christian history: the Council of Nicaea, a gathering that produced a foundational statement of the faith that is still recognized by most Christians around the world.

Many people knew there were ruins in the lake. Locals sometimes used to swim around the stone masonry. But nobody paid much attention.

“It was the difference between looking and seeing,” said Şahin, a scholar at Turkey’s Bursa Uludağ University, as he stood next to the ruins of the Basilica of St. Neophytos, which fully emerged from the receding lake this year because of a prolonged drought.

Pope Leo XIV on Friday visited the ruins in Iznik, as present-day Nicaea is called, to mark the council’s 1700th anniversary. He was joined by clergymen including Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, the most senior bishop in Eastern Orthodoxy. Standing in front of the basilica’s ruins, Leo, Bartholomew and other church leaders recited the Nicene Creed, the shared statement of Christian faith.

“It was an undivided church at that time,” said Metropolitan Emmanuel Adamakis, a Greek Orthodox bishop who helped organize the pope’s trip. “The message is searching for unity again.”

Mustafa Shahin, an archaeologist from Turkey’s Bursa Uludağ University.

The Council of Nicaea was convened by Roman Emperor Constantine in A.D. 325 with the aim of resolving a theological dispute that was threatening to divide early Christendom. Arius, a priest with many followers among the clergy and faithful, disputed the oneness of Jesus with God the Father.

The debate got heated. Arius enraged the attending bishops. St. Nicholas—the bishop who came to be associated with Santa Claus—is said to have punched him in the face.

The overwhelming majority backed the Nicene Creed, which affirmed the full divinity of Jesus, declaring he is “of one substance” and thus equal to God the Father.

The council also agreed on how to determine the date of Easter. Orthodox and Catholic Christians still follow the formula but use different calendars, so the dates only sometimes coincide. Adamakis said discussions with Catholic leaders are searching for a way to celebrate Easter on the same day. “We need to come back to the celebration of Easter together as Christians,” he said.

Where exactly the council took place was a mystery until very recently. The aerial photo that Şahin studied left many questions unanswered. Among them: Why was there such a large basilica on the lakeshore rather than inside Nicaea’s city walls?

Further investigation revealed a place of worship that evolved as Christians went from being a persecuted minority to enjoying the backing of the Roman Empire.

Archaeologists believe the site began as the burial place of Christian martyr St. Neophytos, said to have been killed by Roman soldiers on the shore of the lake in A.D. 303. A decade later, the Edict of Milan decriminalized Christianity in the empire. Christians soon built a shrine over his grave and other Christians were buried next to him.

Many of those early graves, marked by propped up terracotta roof tiles, are visible outside the basilica today. A room near the church’s apse contains fragments of a sarcophagus believed to be St. Neophytos’s. Other discoveries include a votive token depicting Christ offering a blessing. But that didn’t mean the basilica had hosted the historic council.

Şahin found one important clue in Rome in 2018. A fresco in the Vatican Library shows bishops holding the Council of Nicaea in a basilica outside the walls of a fortified city, near a lake.

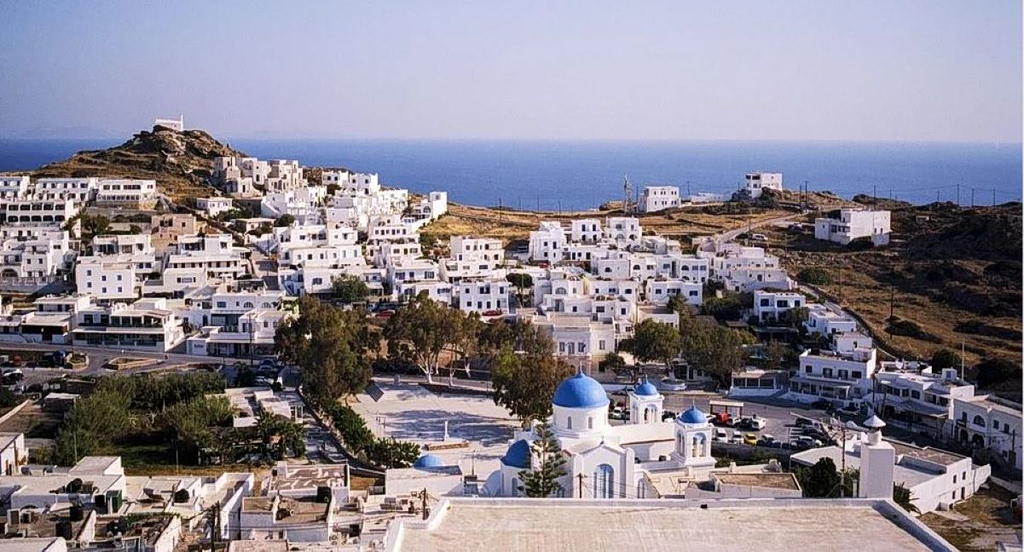

Visitors look at archaeological excavations of the sunken Byzantine Basilica of Saint Neophytos by Lake Iznik, where Pope Leo XIV is expected to visit later this week for the celebrations of the 1,700th anniversary of the First Nicaea Council, during his first trip outside Italy as pontiff, in Iznik, Turkey, November 21, 2025. REUTERS/Kemal Aslan

“This looks like the location of my church,” Şahin recalled thinking. “Until then, I always thought of my church as the Basilica of Neophytos. I never thought that it could be the church where the First Council met.”

The basilica is Nicaea’s only known church from the fourth century. Nails and wooden girders found under its marble floor show how the small shrine became a wooden church and later a stone structure, according to American biblical scholar Mark Fairchild, who teamed up with Şahin to help confirm the findings.

“It was in the wooden structure that the council first met,” said Fairchild. The bishop and Church historian Eusebius, who took part, wrote that the church was tightly packed, and that discussions later moved to an imperial palace, where the Nicene Creed was drafted.

Earthquakes later destroyed the church and left it under the lake.

Iznik’s Christian population is long gone, but its legacy is still visible. The town’s dominant monument is Little Hagia Sophia, a Byzantine church that in the eighth century hosted the last ecumenical council recognized by both the Eastern and Western churches. It became a mosque under the Ottoman Empire and a museum under the Republic of Turkey. In 2011, the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan turned it into a mosque again, one of many ancient churches that in recent years became places of worship for the country’s overwhelmingly Muslim population.

More Christian pilgrims have made their way to Iznik since the papal visit was announced, and numbers are expected to grow. The town’s souvenir shops have begun to sell basilica-themed magnets, ceramics and prayer plaques.