Like a goddess atop Olympus, Eleni Papadaki towered over Greek theatre, and particularly ancient tragedy, throughout most of the first half of the 20th century. At the peak were only two other great, older actresses: Marika Kotopouli and Katina Paxinou. Papadaki was considered to be the successor to the former.

The life and death of the great tragedienne was in many ways as shocking as the heroines of ancient tragedy that she brought to life on the stage, by all accounts incomparably.

The milieu of a murder

The immediate backdrop of her execution was the “Dekemvriana” (the “events of December”), considered to be the precursor of the Greek Civil War. The bloodshed began during a massive protest organised by EAM (National Liberation Front)- ELAS (Greek Popular Liberation Army) – one of the bravest and most effective Nazi resistance movements in Europe throughout WWII – demanding the demilitarisation and purge of security forces.

At that point, the gendarmerie was ordered by Athens Mayor Angelos Evert to open fire on peaceful protesters – 30 were killed and over 100 injured. The event triggered mayhem.

This was the enormously tumultuous political milieu of Papadaki’s murder, but the battles neither caused nor instigated it.

The cause and those responsible for the execution have been a bone of contention between left-wing and right-wing historians and other authors ever since. The definitive biography – Eleni Papadaki: A Brilliant Theatrical Career With an Abrupt End (Kastaniotis Editions, 2001 out-of-print, from which this article draws) authored by Polyvios Marsan, adopts a balanced view and concludes that the charge that she was a traitor was entirely unsubstantiated.

The author puts much greater emphasis on her betrayal by the Greek Actors’ Guild, that expelled her on charges of being a collaborator. The decision was taken by a powerful faction of the union, which included some of Greece’s most famous actors, such as Aimilios Veakis (an erstwhile fan of dictator Ioannis Metaxas who turned communist) and many others who were left-wing members of the resistance National Liberation Front.

A leading role was played by Christos Tsaganeas, a Trotskyite communist who went on to have an illustrious career in film.

Ironically, Veakis and Papadaki had been good friends, had repeatedly acted together, and at one point she had interceded with the Germans to secure the release of his son.

Papadaki’s expulsion from the Guild was based largely on her very close relationship – it was widely rumoured to have been erotic, but there is no conclusive evidence – with the Nazi collaborator prime minister Ioannis Rallis, a Greek Quisling.

Ioannis Rallis: One of Greece’s most hated men

The highly cultivated Rallis, with an aristocratic background (the family traced its roots to Byzantium), and a European education and bearing, had served in top ministerial posts before the German occupation. He appealed to Papadaki.

But as the third and last Quisling prime minister, Rallis became one of the most hated men in Greece due to the savagery of the dread Tagmata Asfaleias or Germanotsoliades (Security Batallions or German Evzones – the former elite royal guard) that he established at the bequest of his Nazi taskmasters in June,1943 law, in order to annihilate EAM-ELAS forces. The battalions were armed by the Wehrmacht and operated under the orders of a German General.

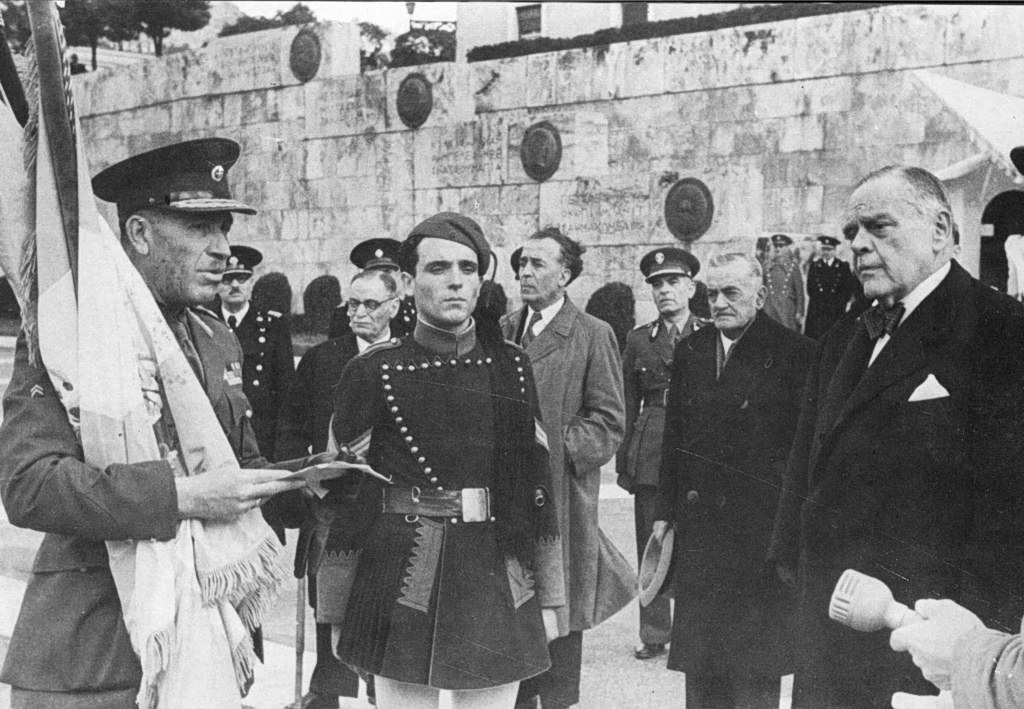

Ioannis Rallis (first from the right) was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 October 1944.

Undertaking militarily crucial blockades, torture, executions, and the handing over of civilians to the Nazis, they were responsible for the killing of an estimated 10,000-20,000 Greeks.

The fateful Papadaki-Rallis liaison

Papadaki and Rallis had close contacts after Rallis, a man of culture and learned, like Papadaki, appointed himself chairman of the single Board for the National Theatre and the National Lyric Opera, and actively participated in the theatre’s affairs and management. They frequently came into contact at social events, and those in the know said he was madly in love with her.

Whether that was reciprocated, we don’t know. However, the late, great song lyricist and author Manos Eleftheriou, who wrote a biographical novel about Papadaki (The Woman who Died Twice), had said that the actress exploited the relationship to advance her career at the National Theatre.

Rallis was also friends with Papadaki’s father, a high-level Ionian Bank employee, before the war.

He was 65 and Papadaki 41-years-old. Though it remains unclear whether there was an erotic element in the relationship, as was widely rumoured, it is certain that there was a deep bond, based on common interests and a shared cultivation.

Had there been an erotic relationship, the married Rallis would have taken good care to keep it under wraps. On frequent occasions, however, Papadaki was seen arriving at the National Theatre in Rallis’s car, with his chauffeur opening the car door for her. Certainly, this does not bear the marks of an illicit love affair.

What is certain is that their bond was not in any way based on politics, with which she had no interest or connection. She was ensconced in her own theatrical world and the adoration of the public for a theatrical diva, a real-life role that appears to have charmed her. It is perhaps for this reason that she was oblivious to the storm that was coming her way.

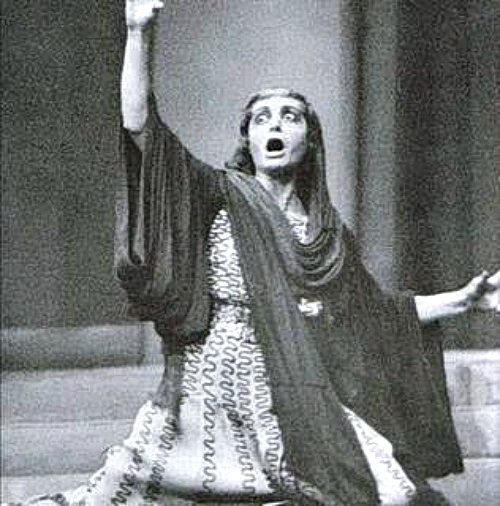

Eleni Papadaki as Antigone, Greek National Theatre, 1940.

Press attacks, the German officer

She paid no attention outwardly to the frequent attacks of the illicit press and others with charges that she was a collaborator, had received lavish gifts from Rallis, and was a whore.

Papadaki had a sound grasp of German, French and Italian, and she had delved deeply into German literature and poetry.

What had been confirmed by accounts of that period is that Papadaki had an affair with a handsome, young German officer with an artistic background. He awaited her outside her dressing room every night.

Obviously, this too was a strike against her.

A consummate actress

Before every performance of a tragedy – from Medea to Hecuba, her last – she studied whatever was written about the play from Greek and German sources to achieve the depth of character.

Greek actress Eleni Papadaki in the role of Hecuba, Greek National Theatre, 1943.

Papadaki managed to get under the skin of the heroines she played – with a voice that was by all accounts mesmerising, with her movement, her cadence, and the pauses that critics said served and complemented the intentions of the great ancient Greek playwrights.

She also played the lead role in over a dozen plays from the 19th and 20th century European repertoire, playing the role of heroines in the plays of playwrights such as Ibsen, George Bernard Shaw, Chekhov, Oscar Wilde and Pirandello.

Saving lives

During the year-and-a half that Rallis served as PM, Papadaki was able to exploit her influence to have the Nazi command release dozens of people from prison, many on death row, including communists, actors and Jews.

Papadaki was by far the most famous of the 17,000 victims nationwide of the 33-day-long Dekemvriana (including government forces, ELAS, citizens).

Expulsion from Greek Actors’ Union

The stage was set for her execution by her own colleagues, when they expelled her from the Greek Actors’ Guild, on the false grounds that she was a Nazi collaborator.

On 20 October, 1944, a faction of the Greek Actors’ Guild voted to expel her and many other actors.

She wrote to the culture minister to demand that they make public the rationale for this decision. She also sent a similar letter to the union but received no reply.

The union at that time had a strong leftist contingent. Though many of them were EAM members, that does not mean they were all communists.

When it expelled Papadaki and others on the false grounds that they were supposedly Nazi collaborators, newspapers carried the banner headline The actors who are traitors.

That set the scene for the final act, her murder. She became easy prey.

OPLA

Papadaki was murdered on orders of the head of a local militia in Athens’ Patissia neighbourhood , with the nom de guerre Captain Orestes. The local militia was a branch of OPLA (Organisation for the Protection of Popular Fighters, or Organisation for Guarding the Popular Struggle).

The dread OPLA tortured and killed thousands of people, mostly with no evidence, as Nazi collaborators or “reactionaries”, including hundreds of policemen and members of the gendarmerie.

It was controlled by the politburo of the Greek Communist Party (KKE).

KKE absolves itself

The looming question is whether Orestes acted of his own volition or was given orders from above. He was a low-level operative who was a petty thief and was responsible for the murder of hundreds, if not thousands. Yet his position as a militia chief gave him some decision-making authority.

Papadaki, however, was one of the most famous and recognisable people in the country. It is difficult to believe he took such a decision on his own.

The Greek Communist Party appointed the leaders of OPLA. At the time of Papadaki’s murder, Yiorgis Santos was the General Secretary of the Greek Communist Party.

The party conveniently claimed that Orestes was a British Intelligence infiltrator, who acted in order to besmirch the party. He confirmed this at his trial, though it is hard to believe that the espionage of a member of such an insular and well-structured organisation could have gone unnoticed. It is conceivable that his testimony was intended to absolve the party.

The party later took care to execute him and others involved in the plot publicly, in Koliatsou Square.

When Nikos Zachariadis – the long-time leader of the party – returned from the Dachau Nazi concentration camp in May, 1945, he again assumed the post of general secretary. In an address to a party conference that year, he referred to the murder of Papadaki.

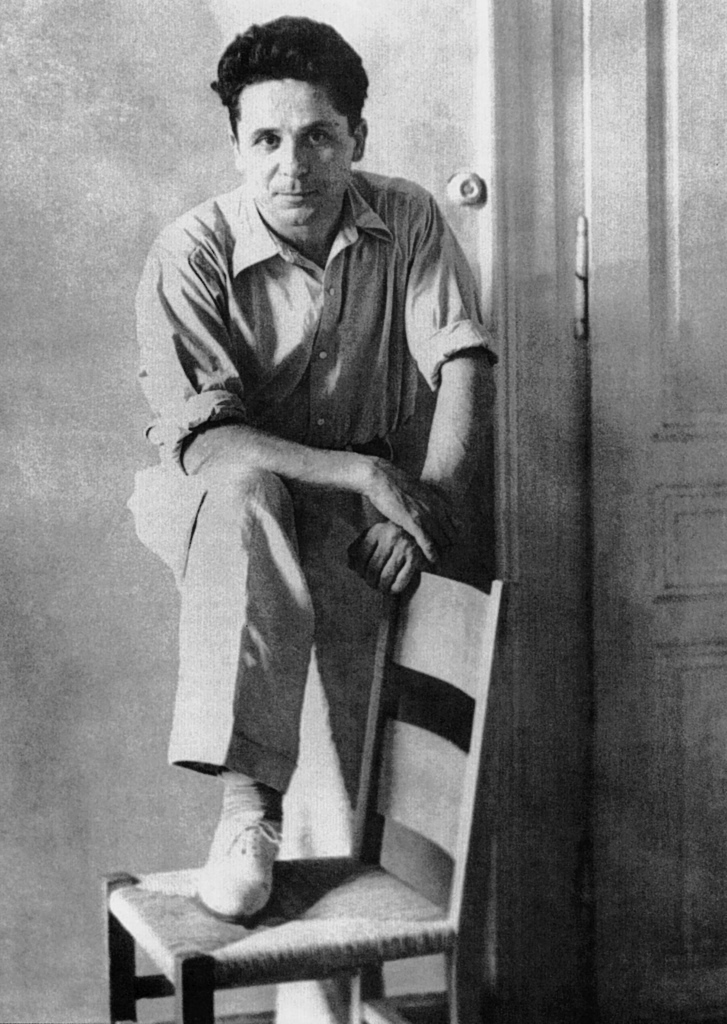

Nikos Zachariadis was the leader of the Communist Party of Greece from 1931 to 1956.

“It was worse than a crime. It was a mistake,” he said.

There could be no more authoritative evidence that the murder of Eleni Papadaki was a choice of the KKE.