Every year, the tiny Greek island of Santorini welcomes millions of visitors from around the world seeking a slice of paradise: a glimpse of a mesmerizing sunset, a sip of intoxicating wine, and a deep breath of air overlooking the spectacular caldera. Few realize that they are gazing into the heart of one of the planet’s most studied and still-active volcanic systems. And even fewer leave knowing even a little about the restless volcano that created it all.

There are no more than 15 dedicated volcano museums in the world. Greece is home to one, but it’s not where you think. Although most of us would expect a museum dedicated to volcanoes to be on Santorini, famous worldwide for its volcanic history, it is instead on Nisyros, a far quieter neighbor that receives a fraction of Santorini’s annual visitors.

One might well find it ironic that Santorini, shaped entirely by volcanic activity and part of a living geological system, remains without a single institution devoted to explaining the phenomenon that created it.

So the logical question is: why doesn’t Santorini have a volcano museum, especially considering its international reputation, its history and the millions of tourists it attracts year round?

Nea Kameni, Santorini Island, Cyclades, Greece

TO BHMA International Edition spoke with volcanologist George Vougioukalakis, former head of the Hellenic Survey of Geology and Mineral Exploration (HSGME) and former president of the Institute for the Study and Monitoring of the Santorini Volcano (ISMOSAV), about why one of the world’s most famous volcanic landscapes continues to tell only half its story.

No volcano museum on Santorini

The short answer? Priorities and local choices, Vougioukalakis tells TO BHMA International Edition.

“Local authorities failed to recognize the importance of such a museum,” he explains. “And as a result, it was never treated as a priority.”

The idea itself is not new. Speaking at an event at the Acropolis Museum last year, Vougioukalakis confirmed that over the years, multiple proposals have been submitted, approved, and in some cases partially implemented. At one point, a historic mansion in Exo Gonia, owned by the Municipality of Thira, was designated to house the museum.

“But there was no continuity,” Vougioukalakis explains. “No persistence in seeing the project through.” Santorini’s early and explosive success as a tourist destination, he argues, played a decisive role. Once mass tourism took hold, long-term scientific and educational projects became harder to justify against short-term economic pressures.

“The focus shifted almost exclusively to maximizing tourism revenue,” he says. “Effectively managing visitor numbers also became a major challenge. In that environment, a volcanology museum was never seen as essential.”

On top of that, the focus on the island’s archaeology overshadowed its geology. When archaeology and science compete in Greece, the former usually wins.

But for Vougioukalakis, not having a volcano museum on Santorini is a missed opportunity.

One of most studied volcanoes on Earth

The absence of a museum is all the more puzzling given Santorini’s scientific importance.

“Santorini is one of the most extensively studied volcanoes on the planet,” Vougioukalakis tells TO BHMA International Edition. “There is an extraordinary volume of data, research and documentation ready to be used in a museum.”

The caldera is among the most thoroughly researched and closely observed volcanic systems on Earth. Its activity has been monitored continuously for decades. Only a year ago, increased activity caused renewed concern among residents and authorities. But also intrigued scientists worldwide.

He acknowledges, however, that turning complex scientific material into an engaging and accessible visitor experience is no simple matter, and would require careful museological design and interpretative work. The foundation already exists, he notes.

What would a volcano museum offer?

This would not be a museum for specialists, Vougioukalakis stresses, but rather for the millions who stand on the caldera’s edge without understanding what formed it.

Looking at the Nisyros Museum and similar examples elsewhere, such as Vulcania theme park in France or Iceland’s Lava Center, it’s clear that Santorini has much to gain from a museum that tells the story of the volcanoes that gave birth to one of the most photographed and visited places on Earth.

The first and immediate benefit would be that accurate information and responsible risk communication would be assured, he says.

“A museum would offer clear, scientifically documented information on volcanic hazards stemming from the reactivation of Santorini’s active volcanoes,” Vougioukalakis tells TO BHMA International Edition. “Residents and visitors would have access to this information, thus preventing misinformation and irresponsible rumors.”

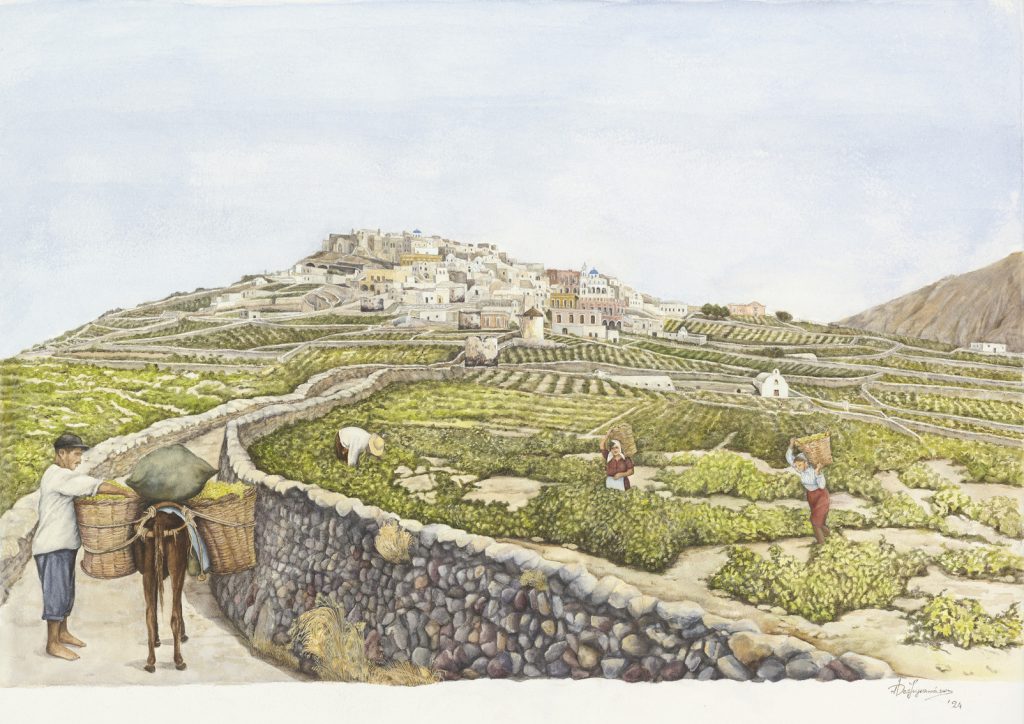

He goes on to add: “everything that makes Santorini unique is the result of its volcanoes. The dramatic landscape and the caldera itself, its unique wine, fava beans, tomatoes and other produce, the lunar terrain of Nea Kameni, the unique island architecture; even the fact that the prehistoric settlement at Akrotiri has survived so well preserved.”

Beyond education, the museum could enrich cruise and culture tourism, encourage year-round visits, ease seasonal overcrowding, and promote a more sustainable development model, particularly at a time when climate risk and geological awareness matter more than ever.

What’s more, Vougioukalakis adds, there is little doubt about its appeal. It would be one of the most visited volcano museums in the world.

Why it matters now

For Vougioukalakis, the timing is critical. “It’s now widely accepted that Santorini’s development model must change,” he says. “The island cannot go on as it has done till now. Volcanic activity in 2011-2012, and again more recently in 2024-2025, have reinforced the need for balance and long-term planning.”

A museum, he argues, would not simply inform; it would become a center of education and documentation, of collective memory; a space that explains both the greatness and the dangers of the volcano.

The example of Nisyros

On nearby Nisyros, a volcanological museum opened in 2008 in a renovated school building in the village of Nikia, perched right on the caldera rim. From there, visitors can hike down paths into the volcanic crater itself. Nearby, you’ll also find the Volcanic Observatory, which tracks seismic and volcanic data around the clock.

Volcano crater on Nisyros Island, Greece.

The Nisyros Museum was created between 2005-2008, says Vougioukalakis, following recommendations from colleagues at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the Institute of Greek and Mediterranean Studies, and thanks to persistent efforts on the part of the Municipality of Nisyros, which secured the relevant funding from the South Aegean Region.

A long-awaited vision

So what’s needed at this stage for the Santorini volcano museum to move forward?

The project has already secured 1.33 million euros in funding from the South Aegean Region and is included in the 2021-2027 regional development program under a social infrastructure pillar, says Vougioukalakis.

“The next step is preparing the documents for the international tender and doing so quickly, so it can be executed within the required deadlines,” he adds.

Looking ahead, Vougioukalakis is confident but cautious. “At this stage,” he says, “the ball appears to be rolling, hopefully towards a successful conclusion. I am confident that, with the requisite scientific support from the Institute for the Study and Monitoring of Santorini Volcano, the Municipality of Thera and the South Aegean Region will move ahead with the creation of the long-planned Santorini volcano museum. It’s what we’ve been dreaming of and striving to create for the last 30 years.”