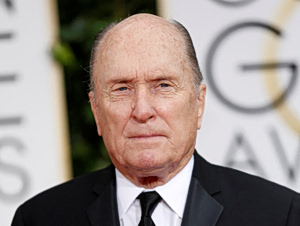

The Rev. Jesse Jackson , a longtime civil-rights activist and Democratic political leader, has died. He was 84.

A gifted public speaker, Jackson was known for fiery rhetoric, often advocating for the interests of working people, especially minorities. In one of his most famous speeches, delivered at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta in 1988, he urged different American groups—Black and white people, liberals and conservatives—to seek common ground.

“Progress will not come through boundless liberalism nor static conservatism,” he said, “but at the critical mass of mutual survival…It takes two wings to fly.”

Jackson, whose death overnight was confirmed by a family spokeswoman, sought the 1984 Democratic nomination for president, becoming the first Black man to wage a nationwide campaign for a major party’s endorsement. He returned to the trail again in 1988, and scored a big win in Michigan, a victory that briefly catapulted him into front-runner status.

Jackson was a favorite among many liberals, who saw him as a strong defender of the disenfranchised, and was disliked by many conservatives and some commentators and politicians, who viewed him as a self-promoter who exaggerated his relationship with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Jesse Louis Burns was born Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, S.C. His mother was Helen Burns, then 16 years old, and his biological father was Noah Louis Robinson, a 33-year-old married neighbor. About a year after Jesse was born, his mother married Charles Jackson, a postal worker who adopted the boy.

Jackson grew up in the segregated South and attended an all-Black high school in Greenville. In 1959, he attended the University of Illinois on a football scholarship but transferred to North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black institution.

In 1960, he and seven other Black people held a sit-in at the public library, which allowed only white people. Police arrested the group, thereafter known as the Greenville Eight, and charged them with disorderly conduct. Jackson participated in marches in Alabama, and Dr. King later tapped him as a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s efforts in Chicago.

After graduating from college in 1964, Jackson studied at the Chicago Theological Seminary but dropped out to work full time for King.

He was at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968, when an assassin killed King. He said at the time he was the last person to speak to King and said he held him in his arms as he died, but other King lieutenants at the motel disputed those claims.

Jackson, who was ordained a minister in June 1968, clashed with the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, one of King’s colleagues and then SCLC chairman, about the group’s direction and who would lead the organization. In 1971, Jackson and supporters left to form the Chicago-based Operation PUSH, which organized boycotts of businesses it stated weren’t doing enough to help minorities.

He believed the U.S. was morally obligated to help improve the lot of low-income people.

“There is something morally degenerate about the system that has the ability to deal with man’s basic problems of poverty, ignorance and disease but does not have the will to do it,” he said on conservative columnist William F. Buckley’s television program in 1971.

Jackson started his campaign for president in 1983, shortly before he organized the Washington-based National Rainbow Coalition in 1984 to press for federal policy changes and more funding to aid poor Americans and minorities. He endorsed full diplomatic relations with Cuba, an independent Palestinian state and full economic sanctions on South Africa, and for reducing the role of the military as a tool of foreign policy.

The campaign drew support from liberal members of the Democratic Party, especially minority groups.

Jackson had “the guts and intellect to take his mark in the starting blocks of mainstream Democratic Party politics” and could defeat then-President Ronald Reagan , Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor and no relation, told the New York Times.

His critics saw the effort and Jackson’s frequent appearances in the media as self-aggrandizing.

“His agenda is the promotion of Jesse Jackson as the king, the emperor, the most important Black person of this century,” Vernon Jarrett, a longtime Black columnist, wrote for the Chicago Sun-Times.

Jackson ran into trouble when he referred to Jewish people as “Hymies” to a reporter and to New York as “Hymietown.” He lost the New York primary to Vice President Walter Mondale , who went on to secure the nomination. The comments would continue to weigh on his political ambitions.

“I am not a perfect servant,” Jackson said at the 1984 Democratic convention in San Francisco. “I am a public servant doing my best against the odds. As I develop and serve, be patient: God is not finished with me yet.”

Despite that setback, Jackson won several primaries and caucuses, becoming the first Black presidential candidate to ever do so.

He ran for president again in 1988. With better organization and financing, he won even more party contests, including in Michigan, Virginia and Georgia. For a brief time, he was considered the front-runner. A Time magazine cover story after Jackson’s sweeping caucus win in Michigan said that for the first time in American history, “a major political party was grappling with one of the biggest what-ifs of all: What if Democratic voters actually nominate a Black man for president?”

But Jackson faded down the stretch, losing the Democratic nomination to Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis. New York again helped sink his prospects. While Jackson drew heavy support from Black voters, he had weak backing among whites, as New York City Mayor Ed Koch rallied against him. Koch famously said Jewish supporters of Jackson, who supported the Palestine Liberation Organization, “have got to be crazy.”

Jackson remained active in Democratic politics, supporting President Bill Clinton and others. He went on several overseas missions in the 1980s and 1990s to negotiate releases of Americans being held in various countries, including Syria, Iraq and Cuba.

In 2001, Jackson announced he had an extramarital affair with a staffer and fathered a daughter.

Fellow Chicagoan Barack Obama ran for and won the presidency in 2008, becoming the first Black president. Jackson publicly supported Obama, but their relationship was strained after Jackson made remarks that were critical of Obama. In one “hot mic” incident in 2008, Jackson was heard to complain that he felt Obama was “talking down to Black people.”

Two of his sons followed him into politics. Jesse L. Jackson Jr., a former Democratic congressman from Chicago, resigned in 2012 during an investigation into alleged misuse of campaign funds. In 2013, the younger Jackson pleaded guilty to violating campaign-finance law and other charges. The elder Jackson wasn’t implicated in any wrongdoing.

Another son, Jonathan Jackson, was elected to Congress from Illinois as a Democrat in 2022, took office in 2023, and was re-elected in 2024.

Jesse Jackson announced in 2017 that he had Parkinson’s disease and said he planned to remain active as long as possible.

“I steadfastly affirm that I would rather wear out than rust out,” he said at the time.

In 2023, he resigned as president of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition. His degenerative disorder was eventually diagnosed not as Parkinson’s, but progressive supranuclear palsy. In late 2025, he was hospitalized in Chicago, and the Rainbow PUSH Coalition said that “the family appreciates all prayers at this time.”

Write to Cameron McWhirter at Cameron.McWhirter@wsj.com